The Era’s Most Fashionable Tobacco Product

Immigration and New York’s Nineteenth-Century Cigar Industry

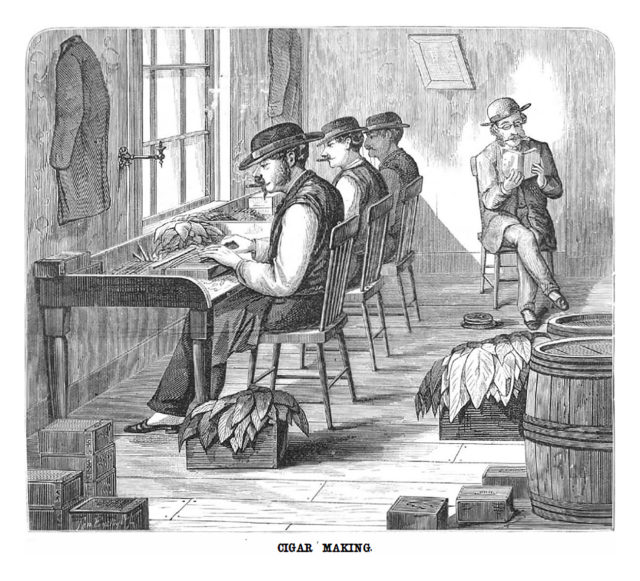

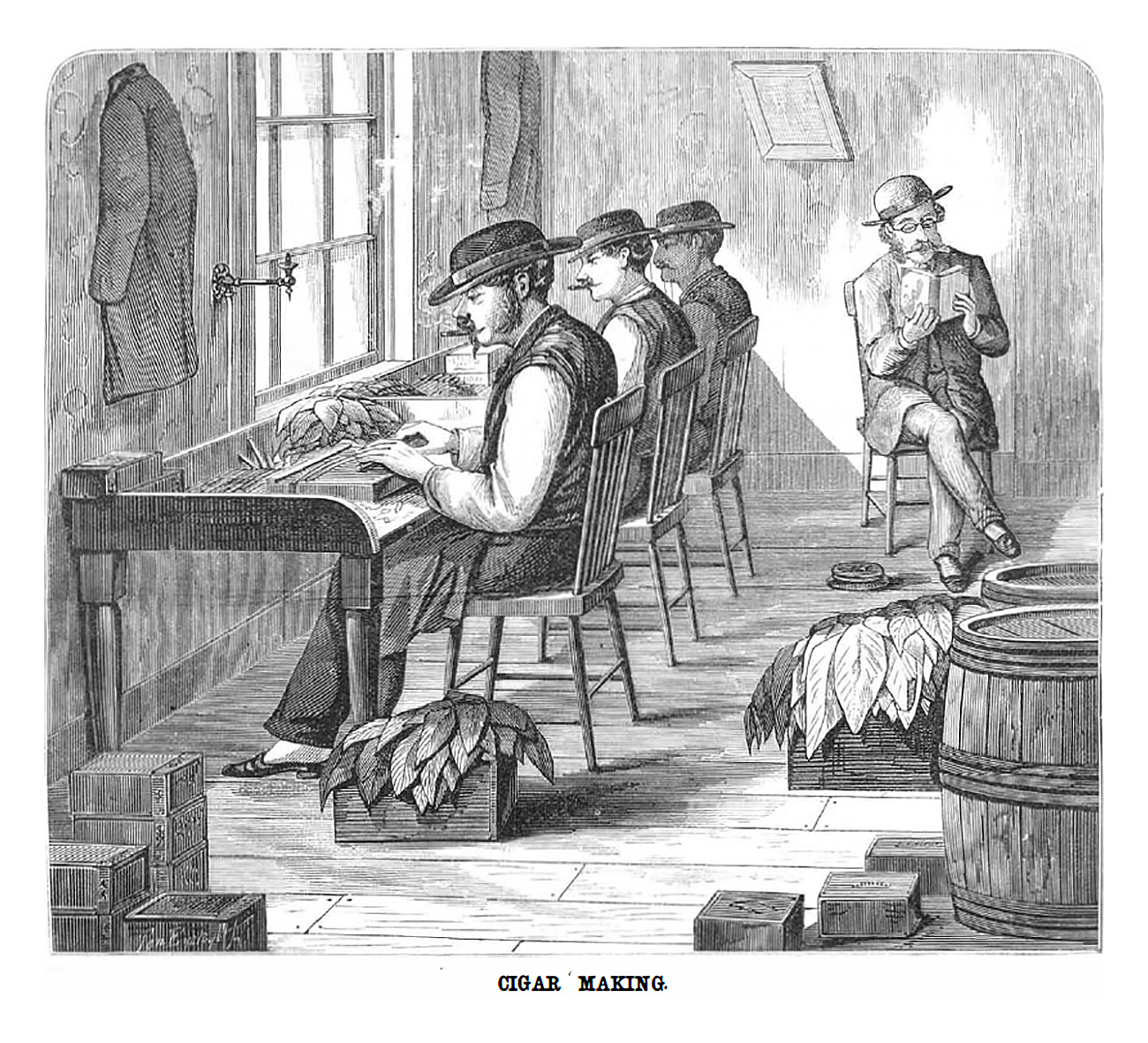

In 1880, the New York City area was the cigar-making capital of the United States. For centuries, pipe tobacco and snuff had been the most sought-after commodities throughout the Atlantic World. Beginning in the 1840s, the arrival of skilled cigar-makers from Europe, particularly German immigrants, gave rise to a robust cigar-manufacturing industry in the Americas.

“Cigar Making”

Scientific American, November 30, 1872

Small shops with fewer than three skilled workers—usually men who rolled cigars by hand—initially dominated the trade. The introduction of cigar molds in the 1870s simplified the process and subdivided production, creating opportunities for unskilled laborers and women. By the turn of the twentieth century, cigar factories with fifty or more workers became common, as did the practice of outsourcing piecework to immigrant and working-class families living overcrowded, factory-owned tenement buildings.

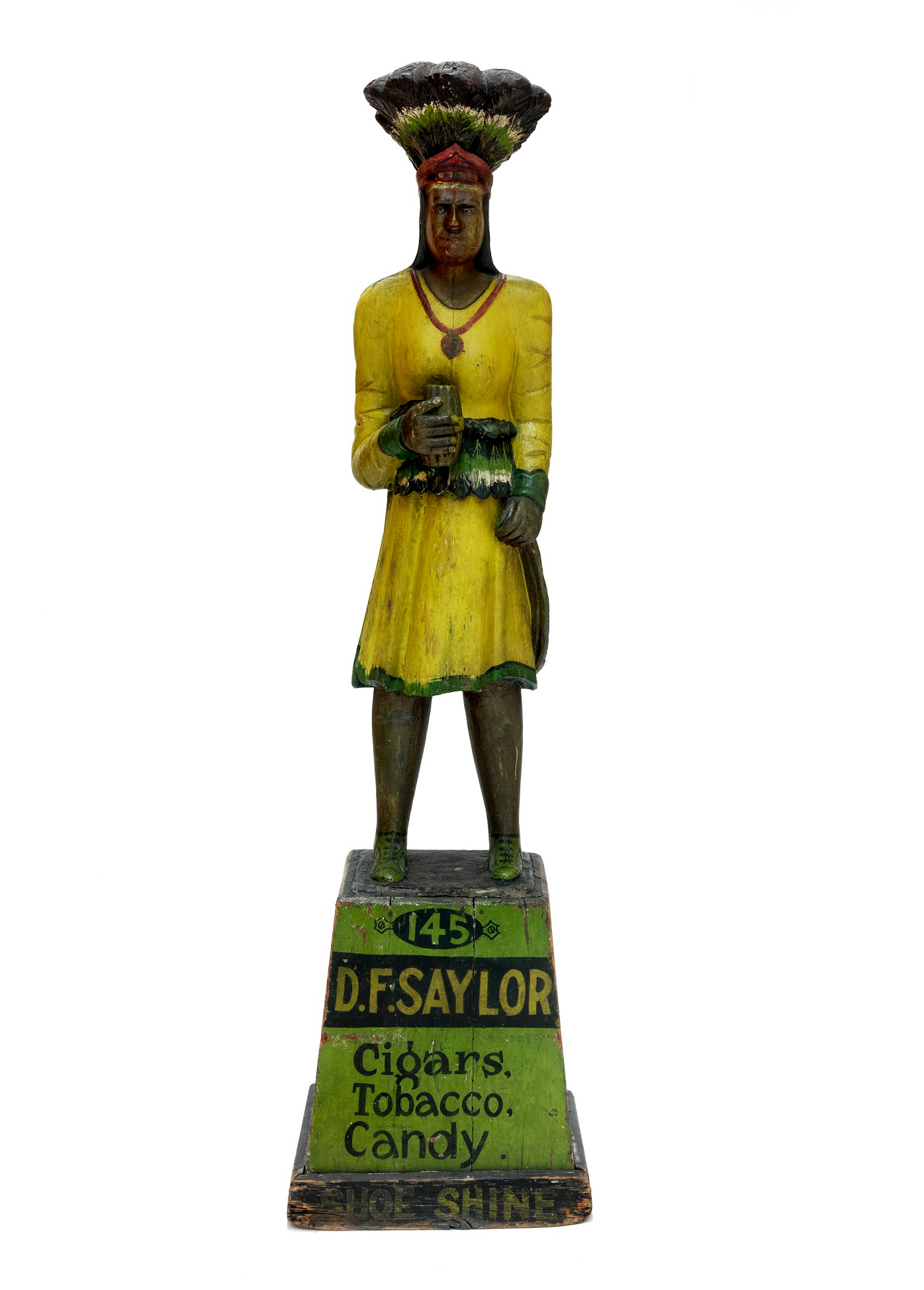

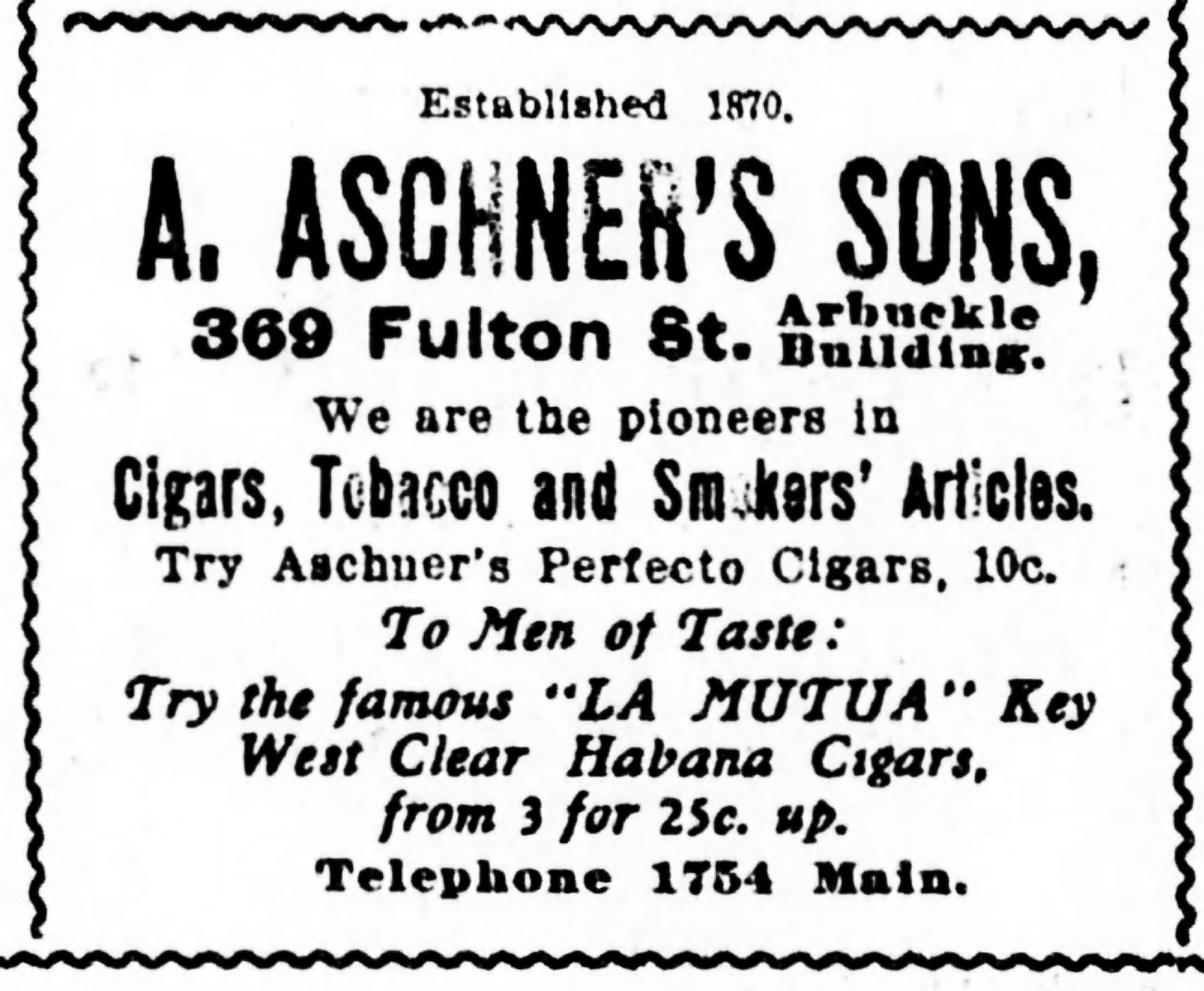

A. Aschner’s Sons advertisement

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 9, 1904

Brooklyn Public Library

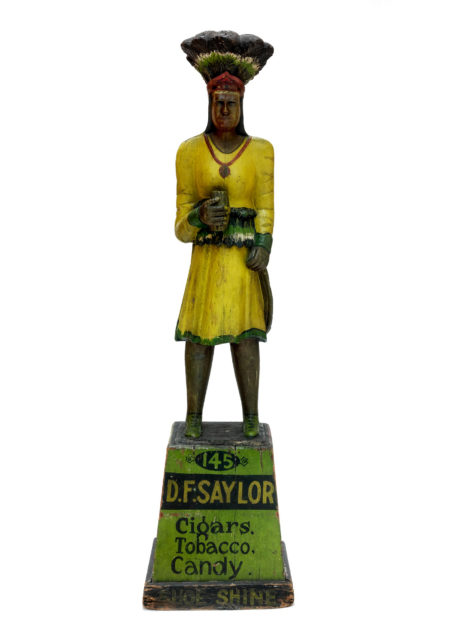

Independent tobacconist shops like those owned by Brooklyn’s Aschner family provided the public with tobacco products and accessories. German immigrant Abraham Aschner opened his first cigar shop in the 1880s and was later succeeded in the business by his sons. A. Aschner’s Sons eventually operated six cigar emporiums throughout Manhattan and Brooklyn. To attract customers, the Aschners placed show figures of American Indians prominently in front of their stores.