The Scars and Relics of Battle

Brooklyn and the Civil War

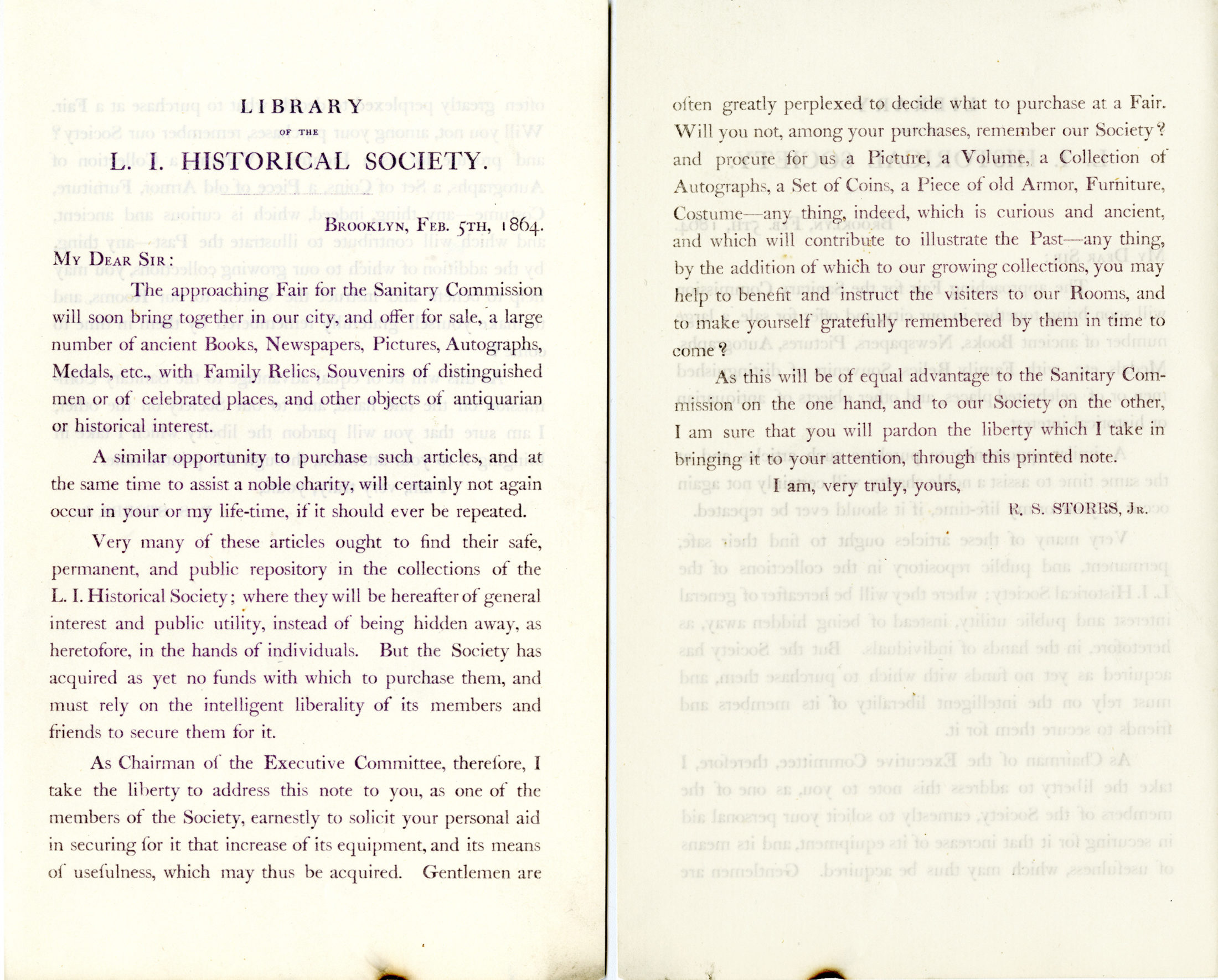

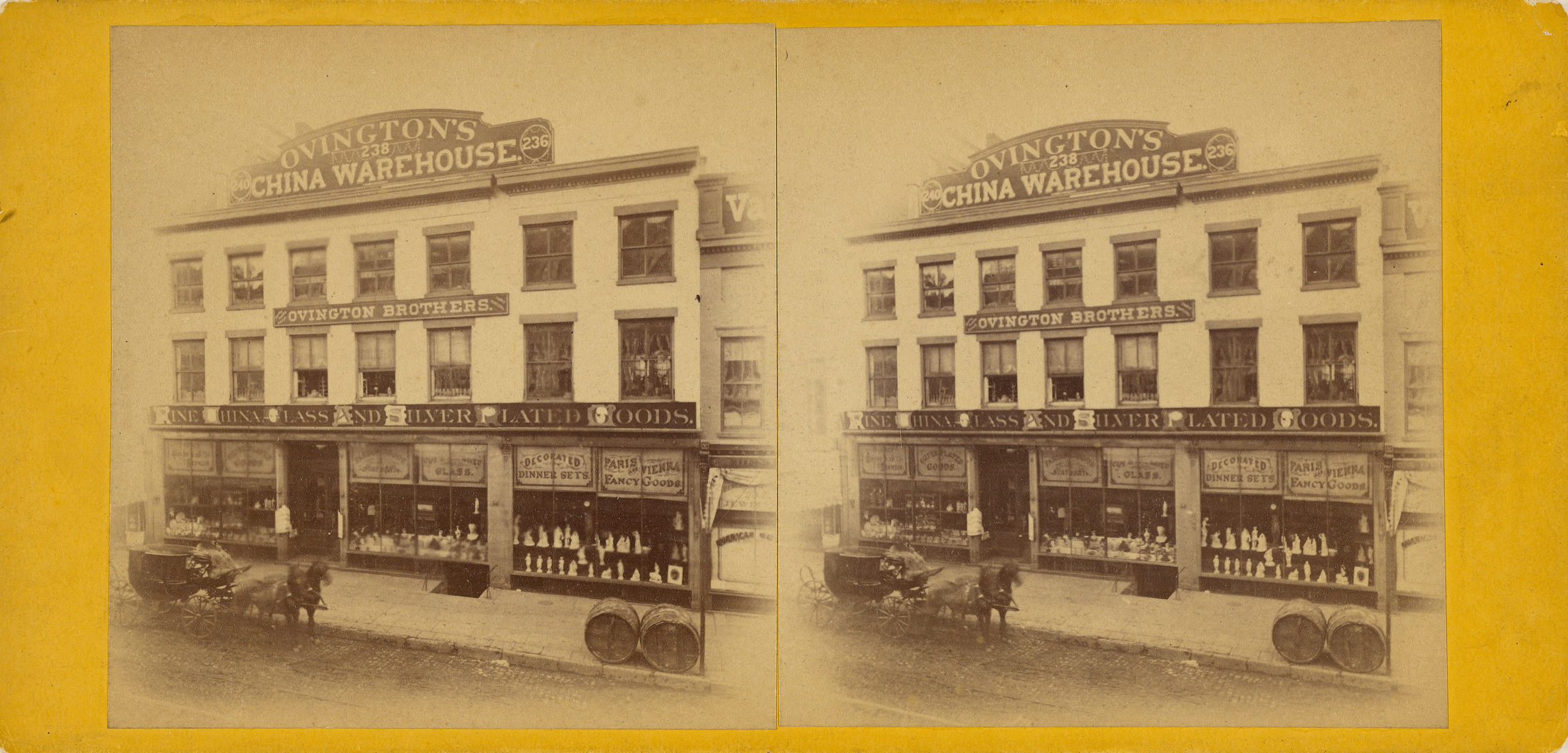

While Ovington’s flag was likely created as a personal display of patriotism, the BHS collection is also home to more than a dozen Civil War–era regimental flags and ceremonial banners associated with New York battalions. Because the Long Island Historical Society was founded during the war, in 1863, the scars and relics of that conflict were among the first items donated for preservation. And while these regimental flags honor the men who served, it is through more intimate war mementoes that the struggles and sacrifices of those soldiers and their families survive.

Civil War Drum, 1861–1862

New York 56th Infantry Regiment

M1983.16.1

Brooklyn Historical Society

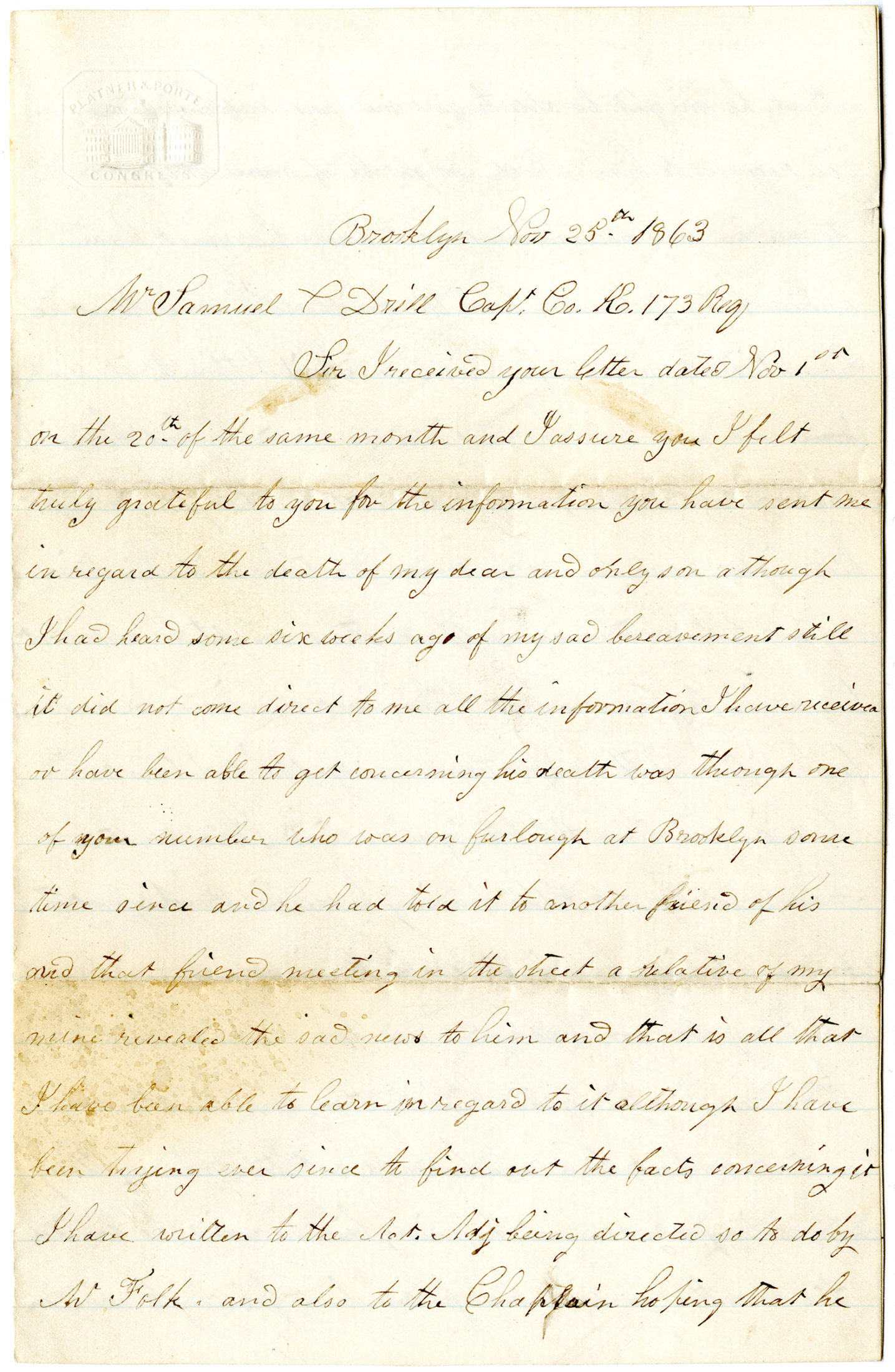

A letter in the BHS collection written by Brooklynite Mary A. Herbert documents her devastation at the death of her only son, Joseph. A member of New York’s 173rd Regiment Company K, Joseph was killed in action on June 14, 1863, at Port Hudson, Louisiana. Mary Herbert waited months for confirmation of her son’s fate, finally receiving word of his death from Nathaniel Augustus Conklin, a fellow Brooklynite from the 173rd Regiment.

Herbert’s grief echoes from the pages of her response to Conklin, embodying the anguish of family members of the deceased. “I feared…I was writing to the dead from not having heard from him in so long a time. Still I kept hoping against fear that it might be from some other cause but not my hopes are all blasted and I am left a lonely widow by the death of my only son.”

173rd Regiment New York Volunteers flag, after 1862

M1989.219.1

Brooklyn Historical Society

A letter in the BHS collection written by Brooklynite Mary A. Herbert documents her devastation at the death of her only son, Joseph. A member of New York’s 173rd Regiment Company K, Joseph was killed in action on June 14, 1863, at Port Hudson, Louisiana. Mary Herbert waited months for confirmation of her son’s fate, finally receiving word of his death from Nathaniel Augustus Conklin, a fellow Brooklynite from the 173rd Regiment.

Herbert’s grief echoes from the pages of her response to Conklin, embodying the anguish of family members of the deceased. “I feared…I was writing to the dead from not having heard from him in so long a time. Still I kept hoping against fear that it might be from some other cause but not my hopes are all blasted and I am left a lonely widow by the death of my only son.”

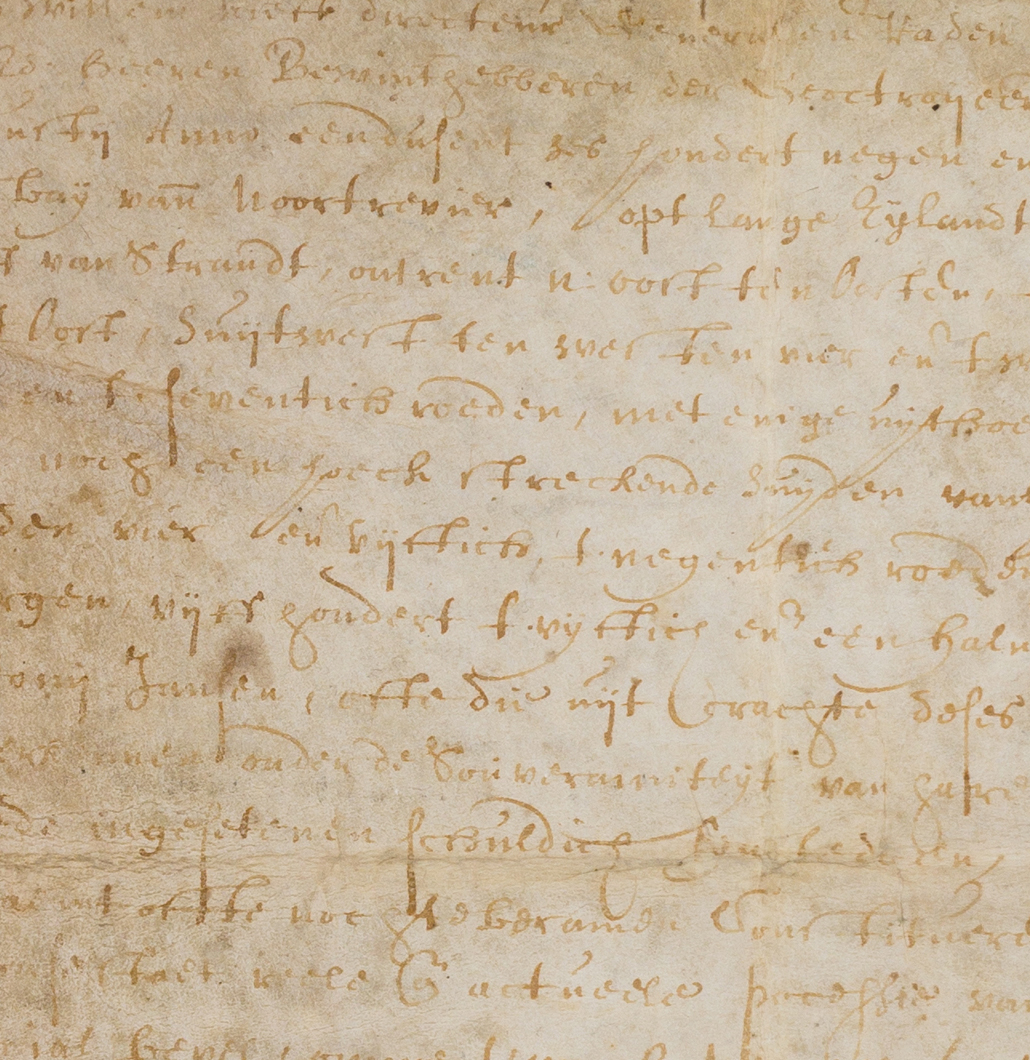

Letter from Mary A. Herbert to Nathaniel Augustus Conklin, 1863

Conklin and Bedell families papers (2005.021)

Brooklyn Historical Society