“Did anyone ever suspect that Indians still lurked on Brooklyn Heights?”

The Erasure of Brooklyn’s American Indian History and Culture

“Did anyone ever suspect that Indians still lurked on Brooklyn Heights?” Brooklyn Eagle Magazine writer Lillian Sabine posed this question in 1930 in a feature article about the seated Indian show figure now in the BHS collection. Sabine’s article honored the sculpture as a neighborhood landmark. Reading the article today, however, casual racism in comments like the one above one stick out sharply, evidence of a deep-seated racial bias in America towards American Indians, one borne from the long exploitative process of American expansion.

“The Neighborhood Indian Passes On”

Lillian Sabine

Brooklyn Eagle Magazine, March 30, 1930

With his dignified, stoic appearance, BHS’s seated Indian sculpture is a classic representation of the “noble savage,” a popular literary hero figure who accepted his fate—extinction—with grace at the advance of modern civilization. In the 1800s, stereotypes like the “noble savage” perpetuated the idea that America’s indigenous communities were a “vanishing race,” their slow disappearance leaving settlers free to inherit the United States. This romantic narrative concealed the reality of the involuntary and violent displacement of American Indian communities from their homelands throughout the country’s history, including the Lenape, who for centuries called the region now known as Brooklyn, home.

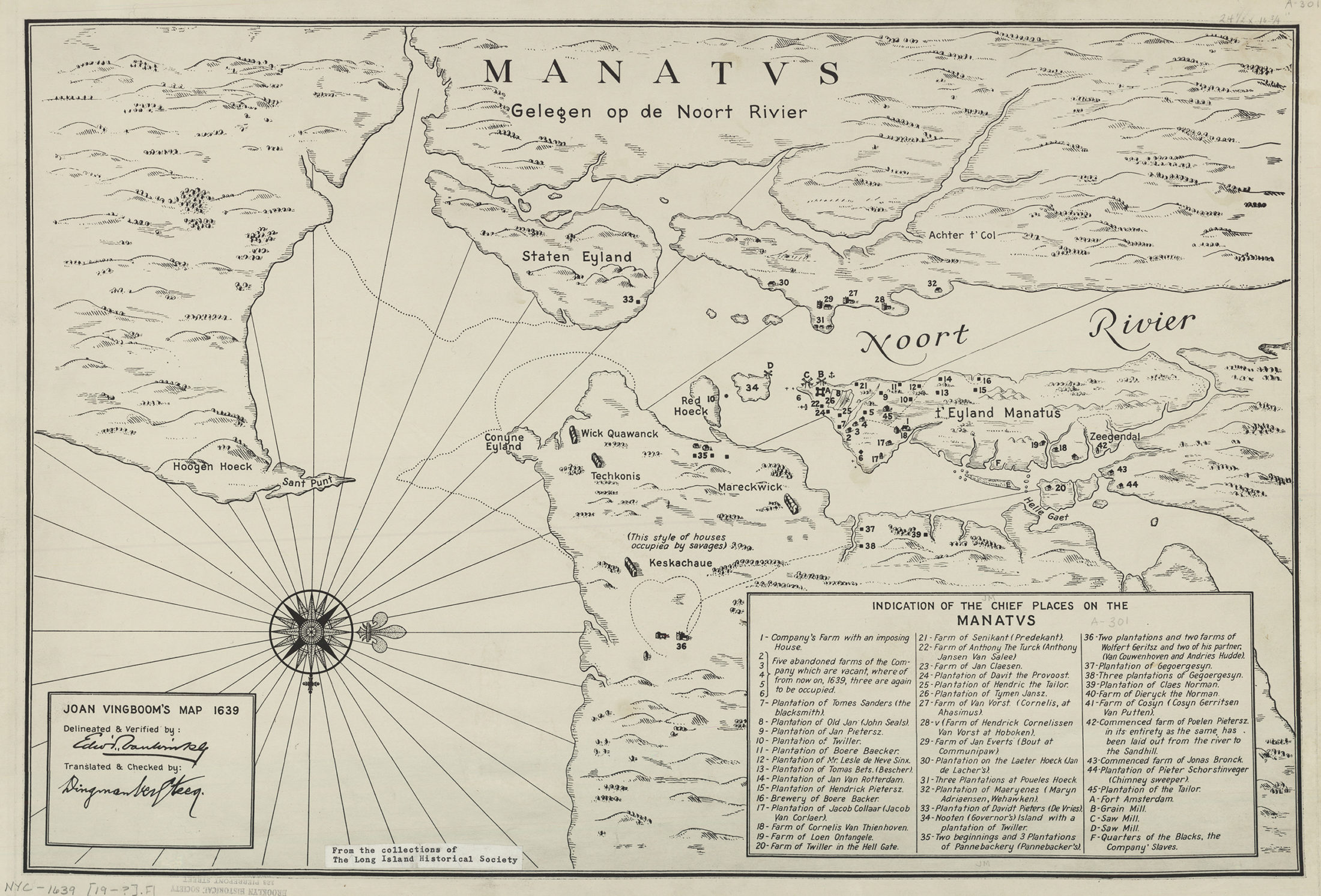

The Lenape were multiple, distinct, seminomadic communities who lived throughout western Long Island, New Jersey, southeastern New York, eastern Pennsylvania, and northern Delaware. In the 1630s, when European incursion began into what is today Brooklyn, settlers arranged land purchases with the Lenape, arrangements understood differently by the individuals involved. Subsequent conflicts led to warfare, and the introduction of European diseases like smallpox decimated Lenape communities. Those who survived eventually fled their ancestral homeland, which they called Lenapehoking.

Joon Vingboom’s map 1639, 1916

Edward Van Winkle

NYC-1639 (19–?).Fl

Brooklyn Historical Society

Despite the fact that the reality was considerably more complex, by the mid-1800s, Brooklyn historian Gabriel Furman felt confident enough to write that the Lenape “are at this time totally extinct; not a single member of that ill-rated race is now in existence.” The Lenape were not extinct. They were displaced, surviving members forced farther West from the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries. Today, the descendants of the dispossessed Lenape live as far afield as Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Ontario, Canada, but their connection to Lenapehoking remains strong.

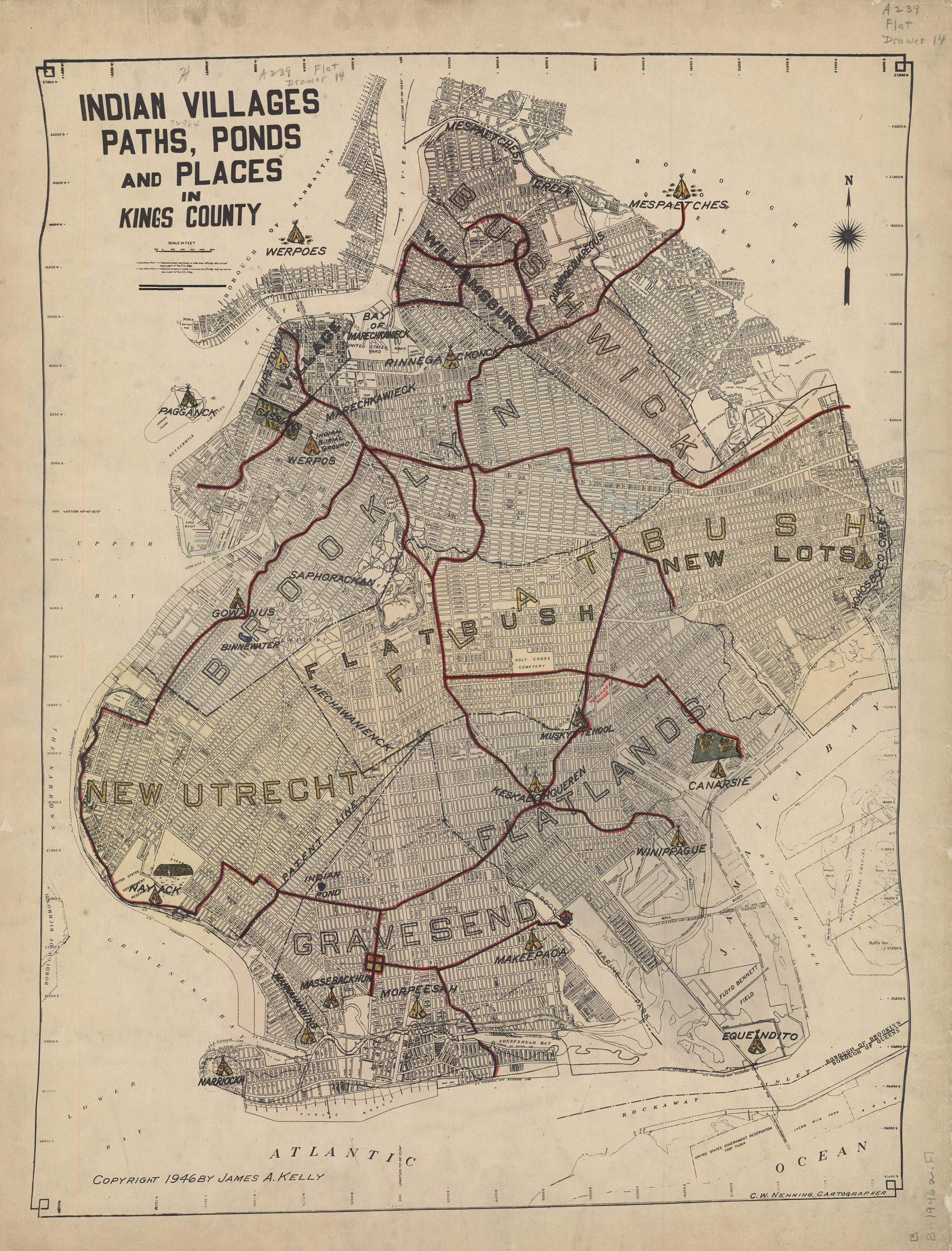

The Indian Villages, Paths, Ponds, and Places of Kings County, 1946

James A. Kelly

B B-1946.Fl

Brooklyn Historical Society

The physical reminders of American Indians living in Brooklyn have largely been swallowed today by the European settlements that grew on top of the “villages, paths, and ponds” of the Lenape. That difficult history should be acknowledged, as should the significant role that artifacts like this sculpture played in erasing the history of American Indian displacement and oppression.