The First Known Person of Muslim Original in America

Introducing Anthony Van Salee

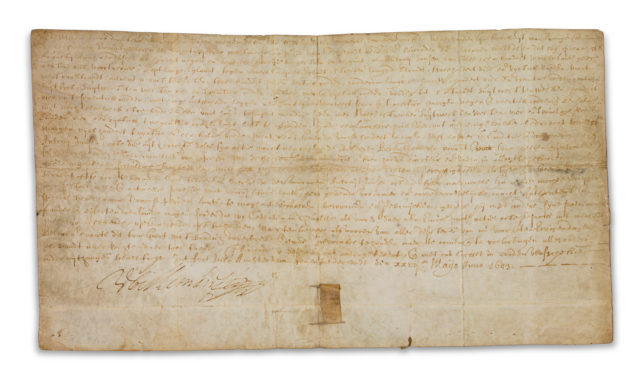

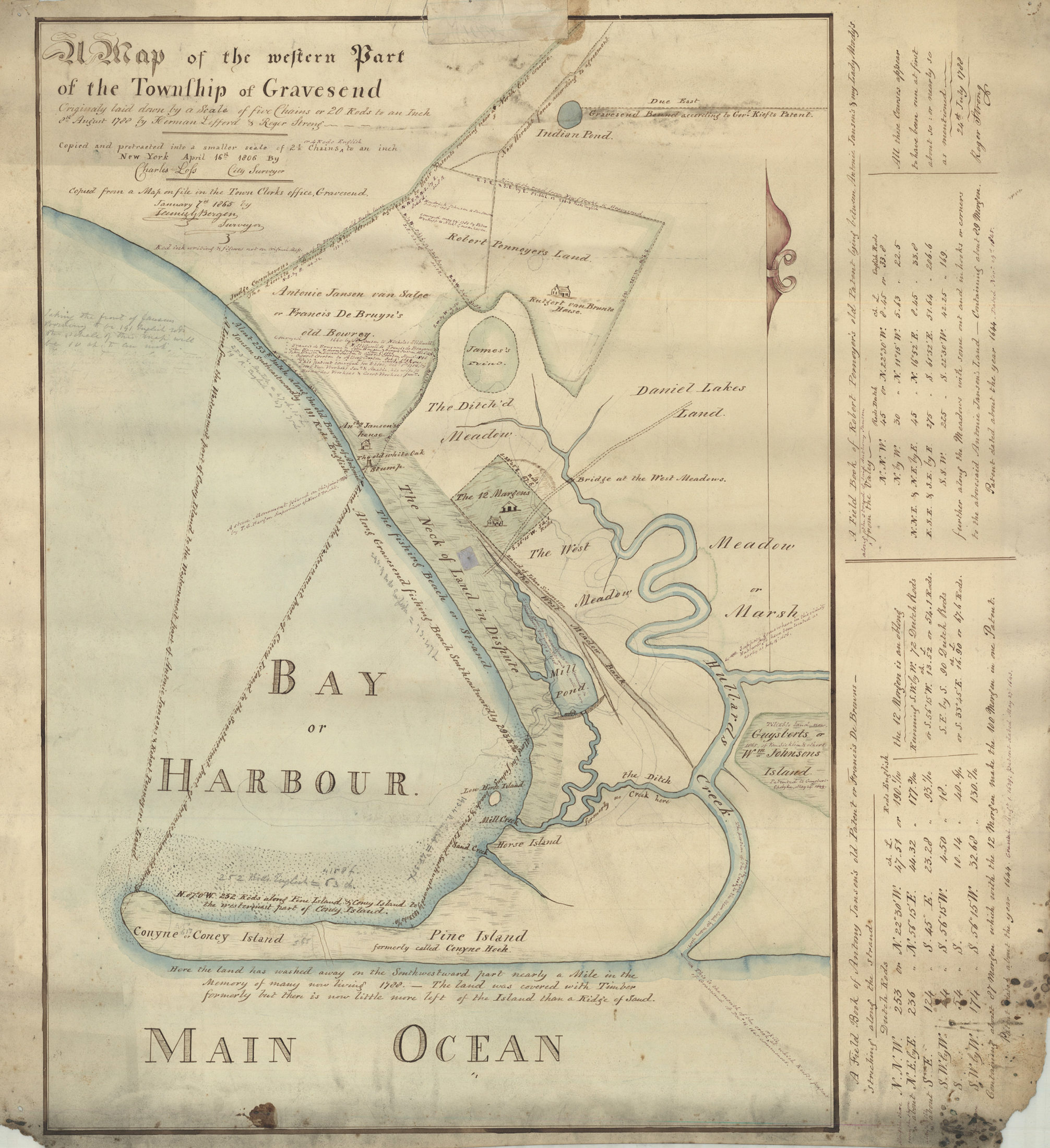

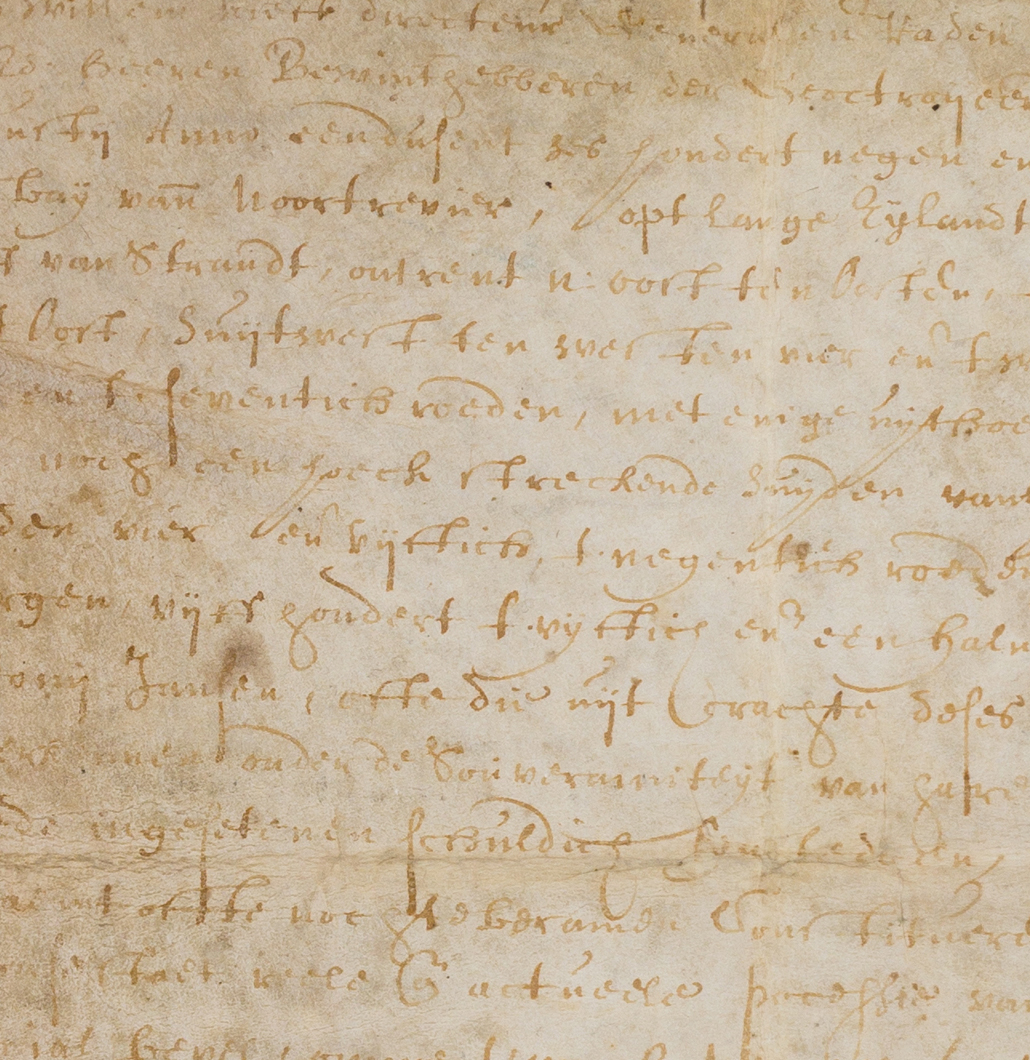

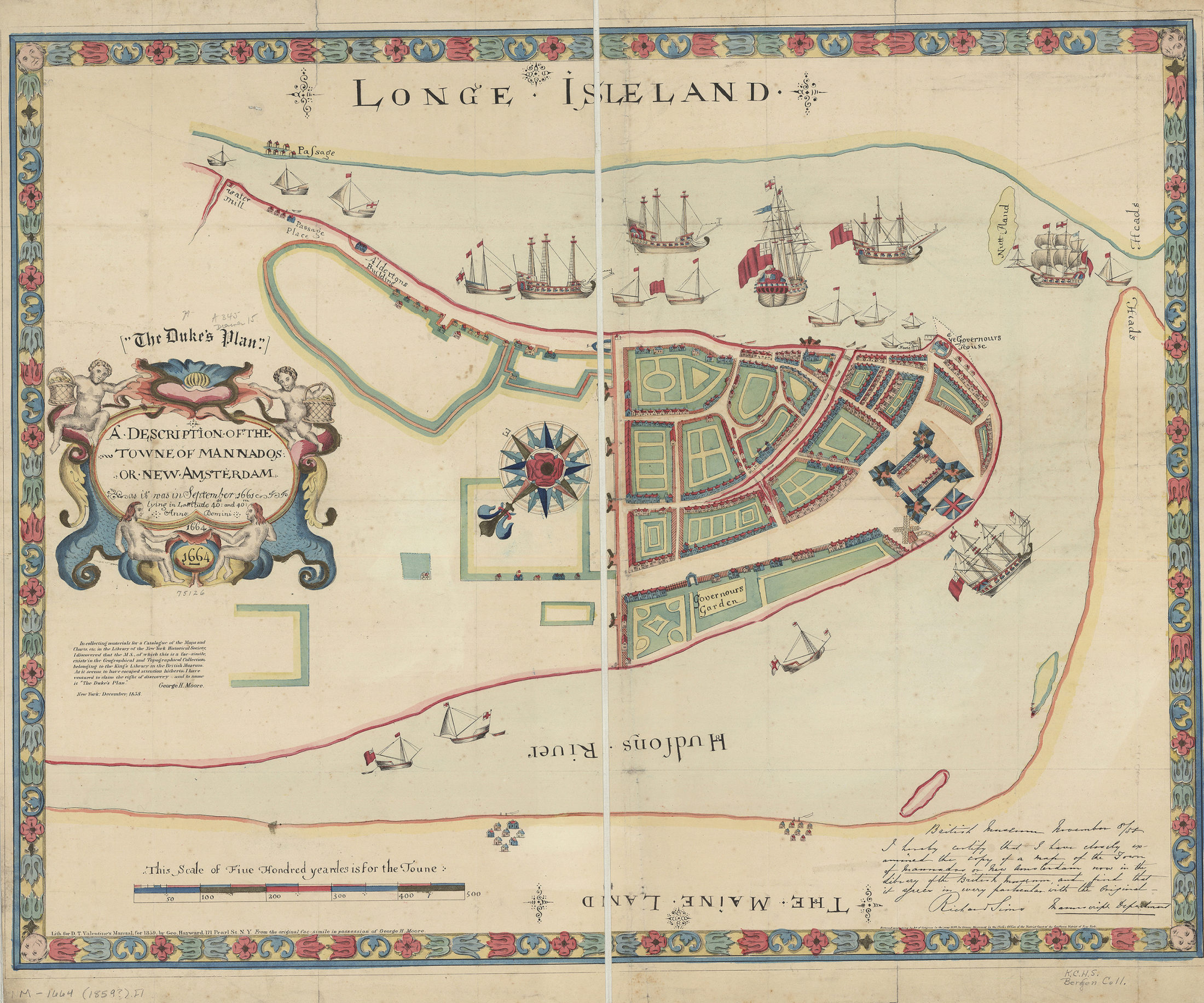

Written in Dutch, this legal document records New Amsterdam Governor William Kieft’s 1639 land grant of 100 morgens (200 acres) of land to Anthony Jansen Van Salee on western Long Island just north of Coney Island. Land deeds and conveyances are plentiful in the BHS collection, but this one is unique because of its recipient.

Anthony Jansen Van Salee (1607–67)—also called Anthony from Salee or “Anthony the Turk”—was the first known person of Muslim origin in the Americas. His story casts new light on the history of Dutch New Amsterdam and exemplifies the immigrant experience that has shaped New York City and Long Island for centuries. New research is only beginning to shed light onto the many diverse Long Islanders whose histories are emerging from obscurity.

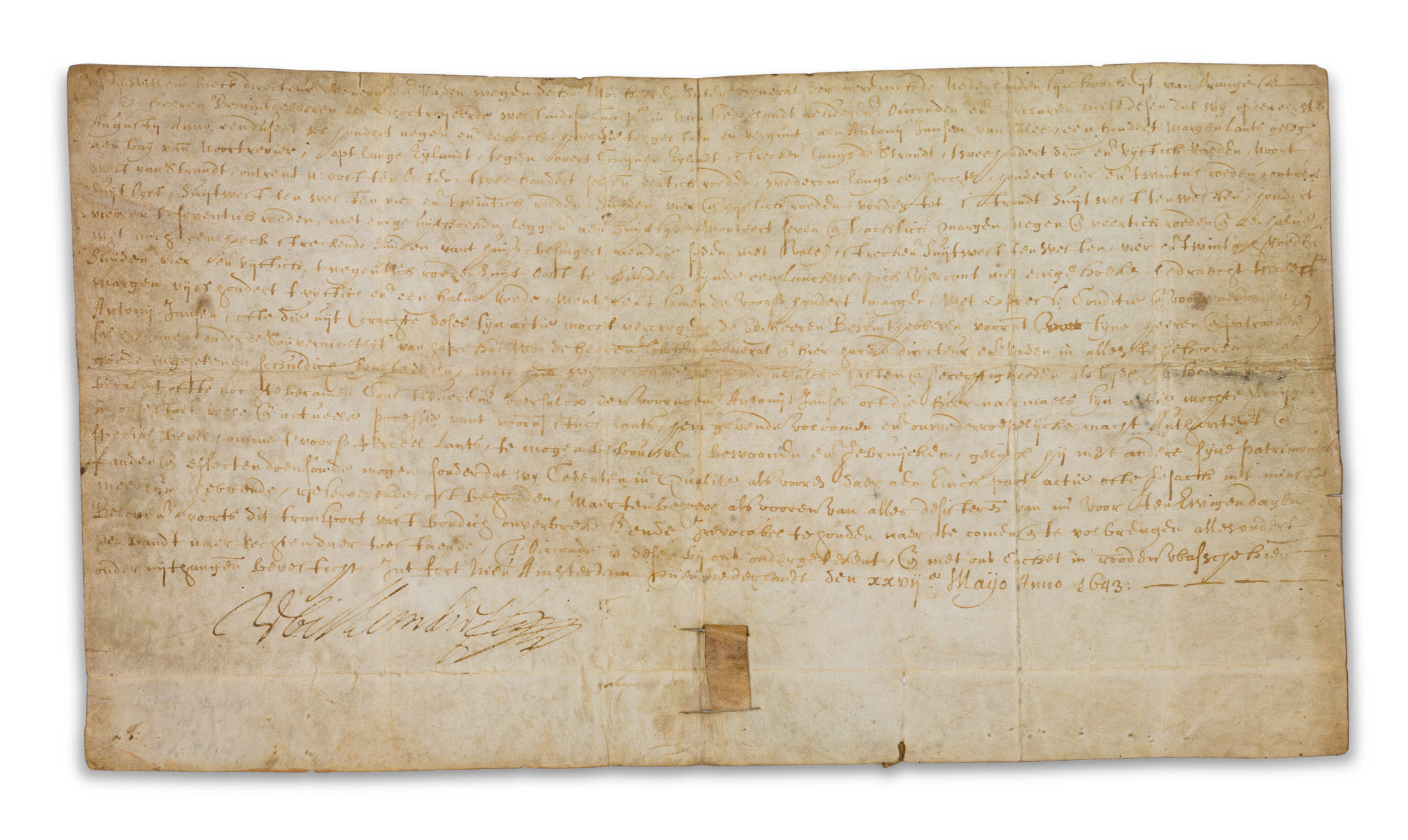

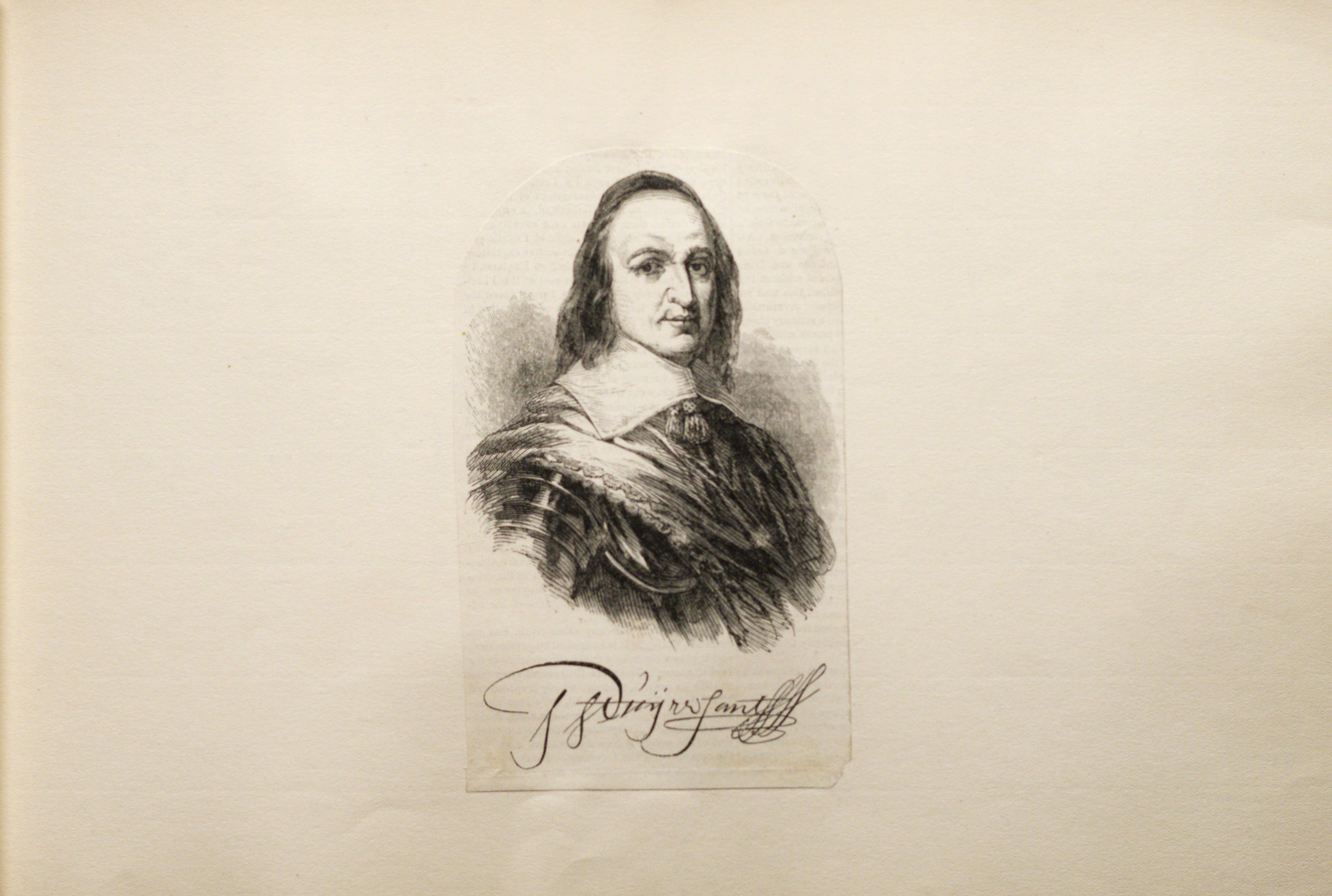

Land deed in Dutch signed by Peter Stuyvesant, 1661

Lefferts family papers (ARC.145)

Brooklyn Historical Society

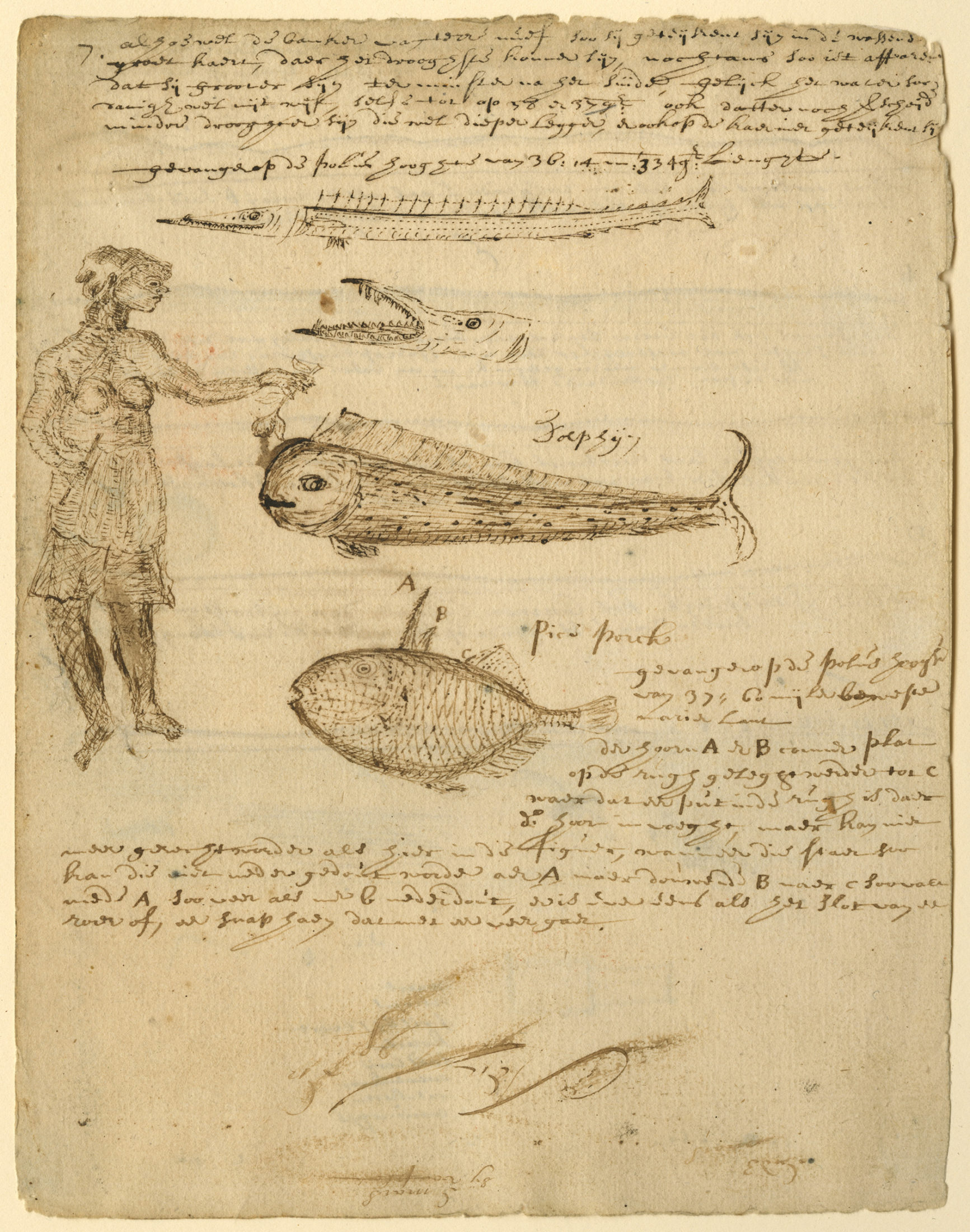

People of color were central to the development of New Amsterdam from the beginning. Founded in 1624 as a colony of the Dutch East India Company, the first enslaved Africans were imported to present-day New York just a year or two later. Enslaved laborers tilled agricultural fields, worked on ships as part of the critical fur trade, and built the new settlement’s essential infrastructure: its wharves, mills, roads, and fortifications.

Upon Van Salee’s arrival in New Amsterdam at the end of 1629 with his wife, Grietje Reyniers, government officials described him as a “mulatto” or as the “Turk” in their records, a direct reflection of his skin color and mixed ancestry. Anthony’s father, Jan Jansen, had been a Dutch privateer; his mother a Spanish Moor. Although there is no direct evidence to prove that Van Salee practiced Islam in the New World, his mixed ancestry and religious heritage eventually brought him and his wife into direct conflict with their New World neighbors, shaping the family’s future in New Amsterdam.

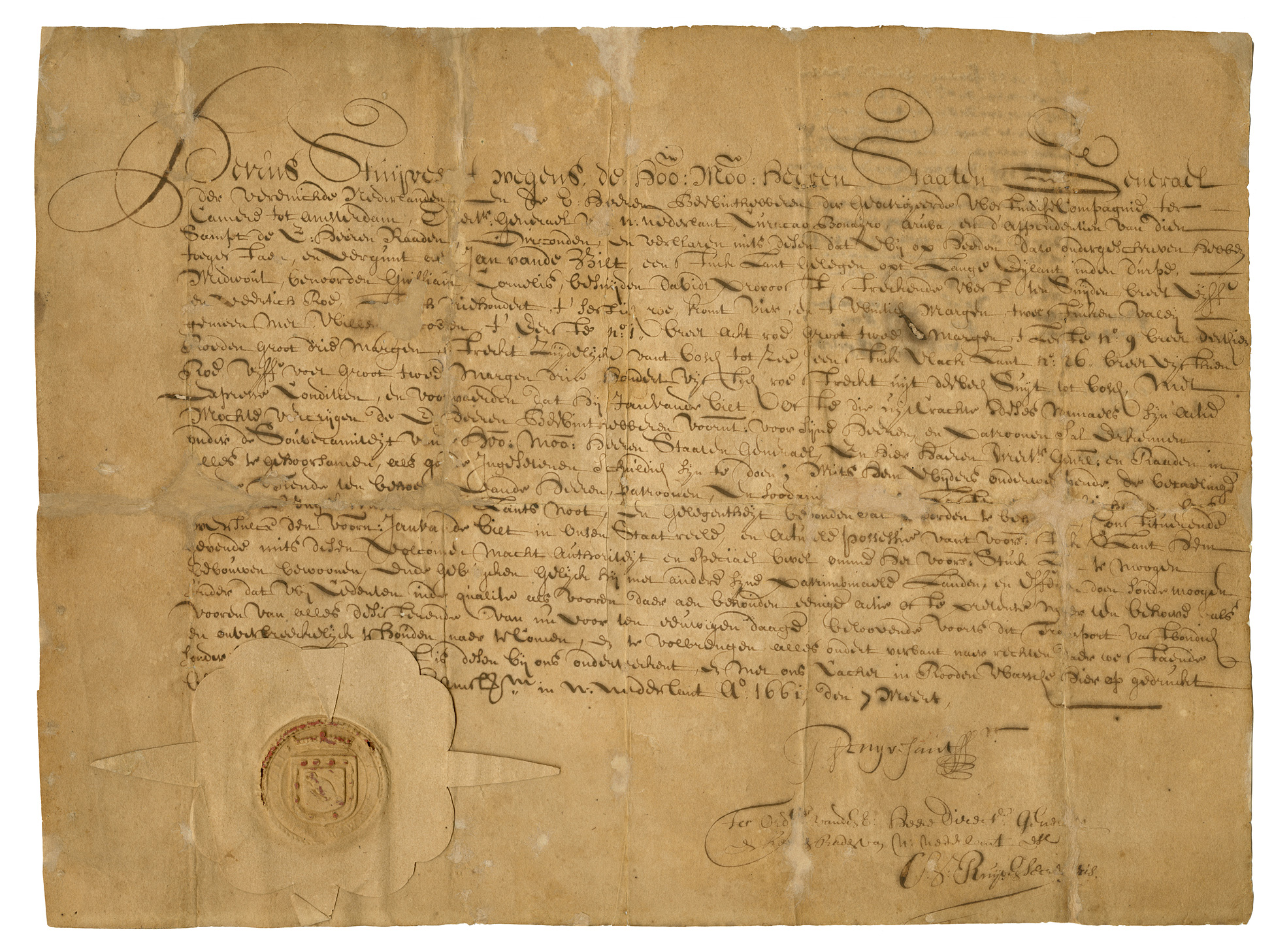

Nieuw Amsterdam ofte nue Nieuw lorx opt’t Eylant Man, 1660

Rijksmuseum

By 1638, the couple had established their own bouwery (farm) just north of the city wall, known today as Wall Street. That year, Everadus Bogardus, dominie (or minister) of the Dutch Reformed Church, sued Van Salee for unpaid debts towards Bogardus’ salary. Accusations of dishonesty from both sides turned into a grudge that blossomed into fifteen civil suits in the next year. The escalating conflict drew forward more community members, many of them friends of Bogardus, with testimony challenging both Anthony’s and Grietje’s conduct and character. To defame the couple, some accused Grietje of lasciviousness and even prostitution.

Ultimately, overwhelmed by testimony documenting the “various troubles” the coupe had caused the community, Governor Kieft made the unusual decision to banish them from the jurisdiction of New Netherland. Although New Amsterdam’s diversity and supposed “religious tolerance” is widely celebrated, the Van Salee’s story is illuminating. Their difference was only marginally tolerated until they directly challenged the state religion and authority.

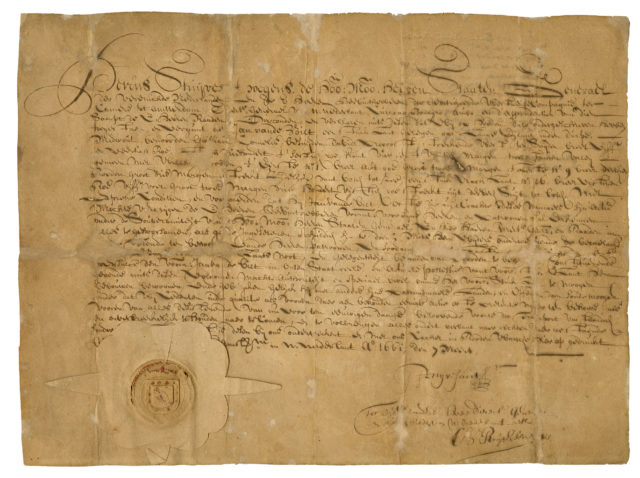

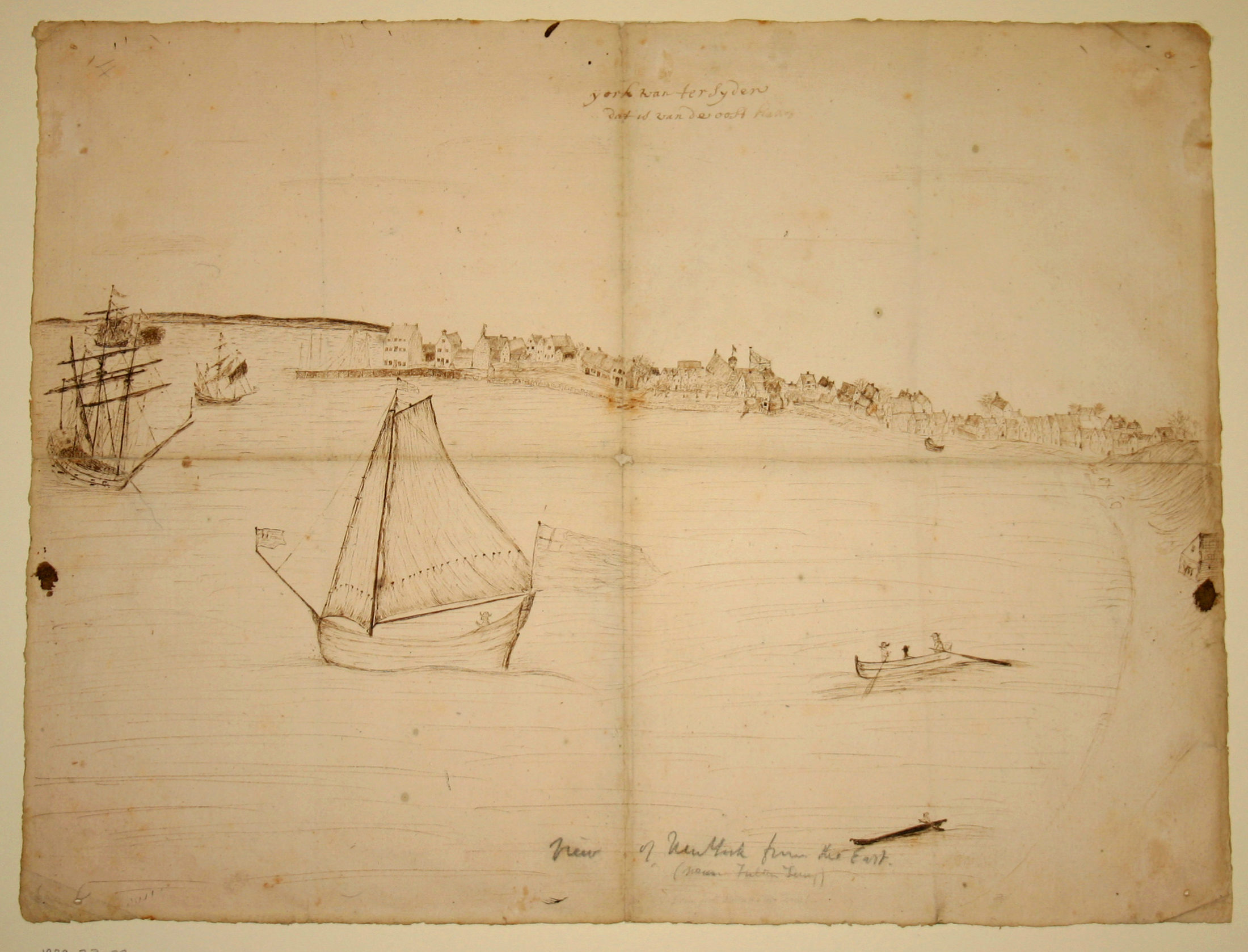

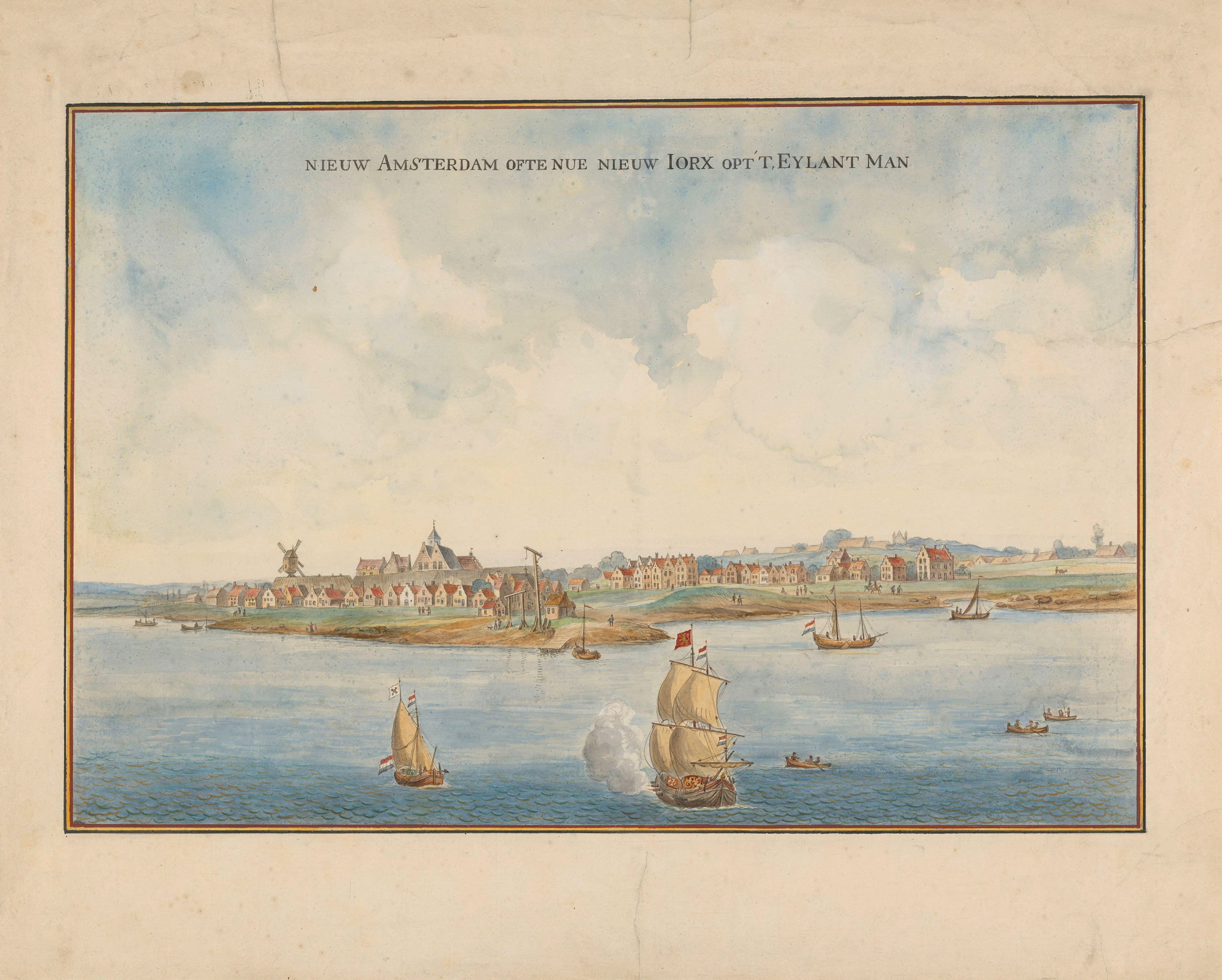

A description of the towne of Mannados or New Amsterdam as it was in September 1661, 1859 [1664]

M-1664 (1859?).Fl

Brooklyn Historical Society

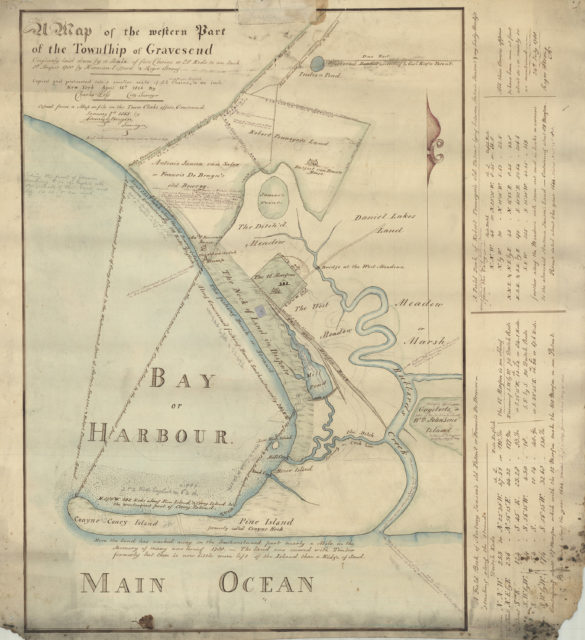

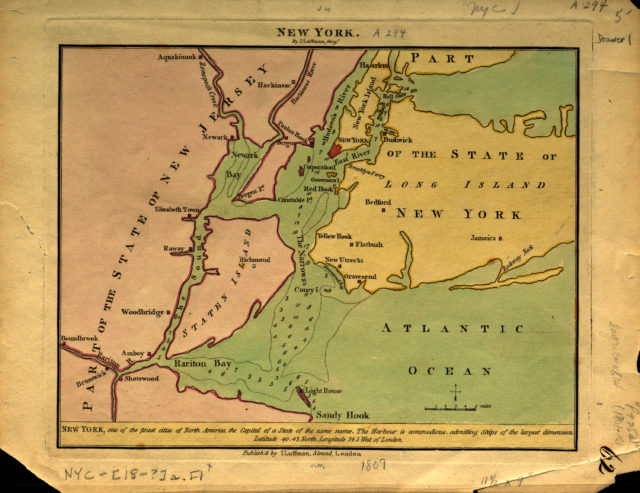

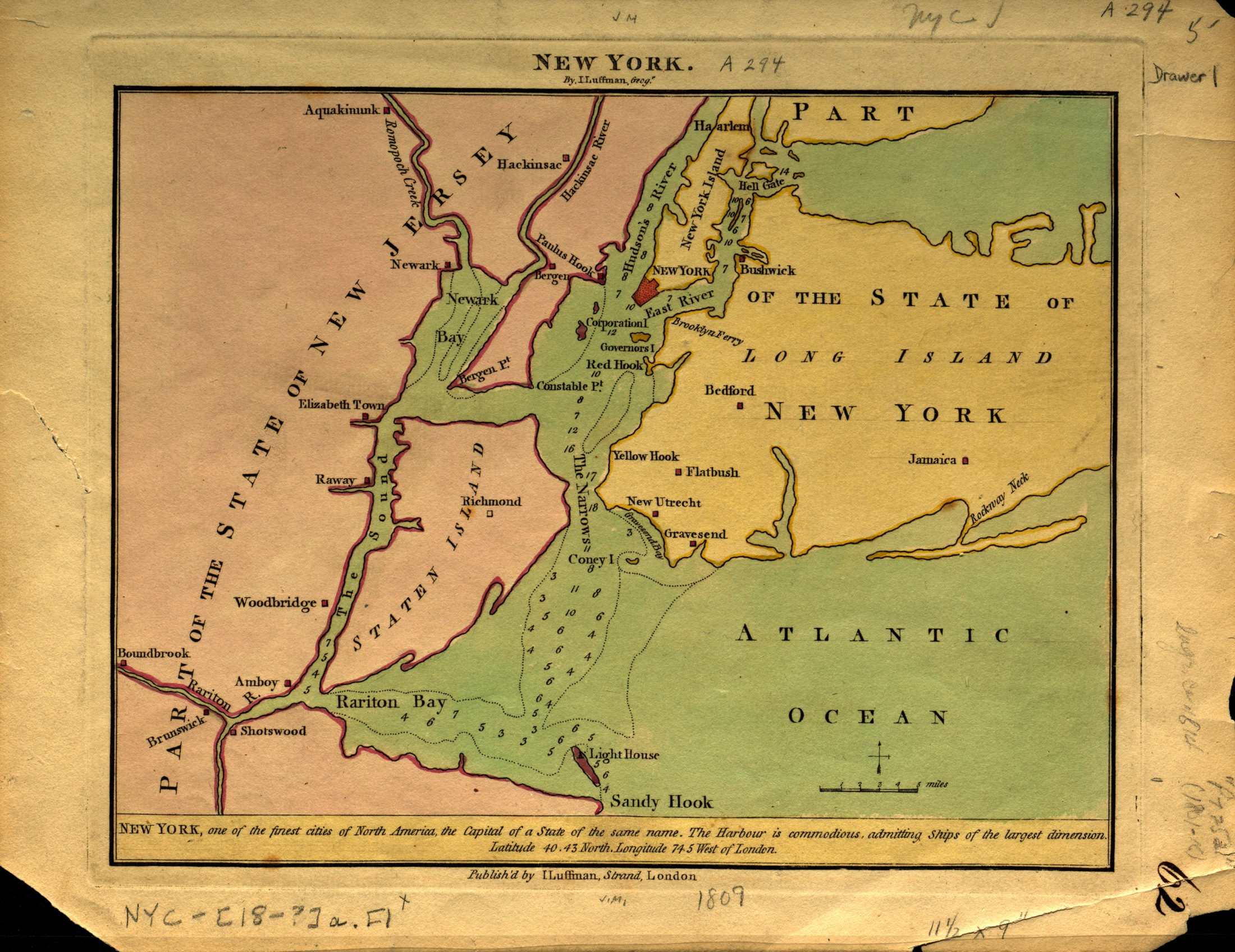

Van Salee nevertheless came out ahead. Governor Kieft approved his request for land on New Amsterdam’s far frontier on the southern tip of western Long Island. With their 200 acres, Anthony and Grietje were among the first European landholders in the area of New Utrecht and Gravesend, where they thrived. Their four daughters went on to marry into prominent merchant families. Today, members of the Vanderbilt family trace their lineage to Anthony Van Salee and Grietje Reyniers.