“Our land will then take such a rise”

The Growth and Suburbanization of Queens County

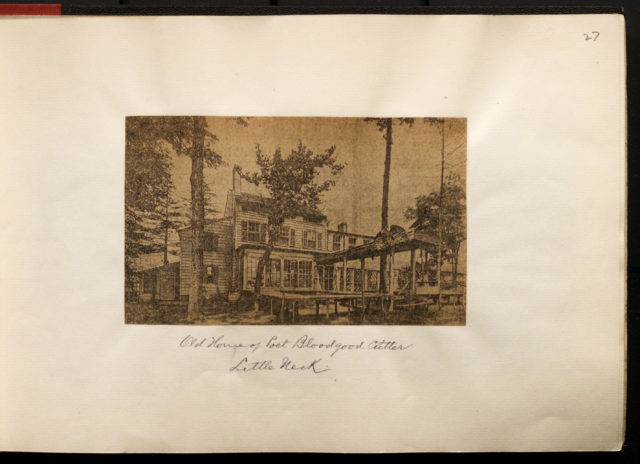

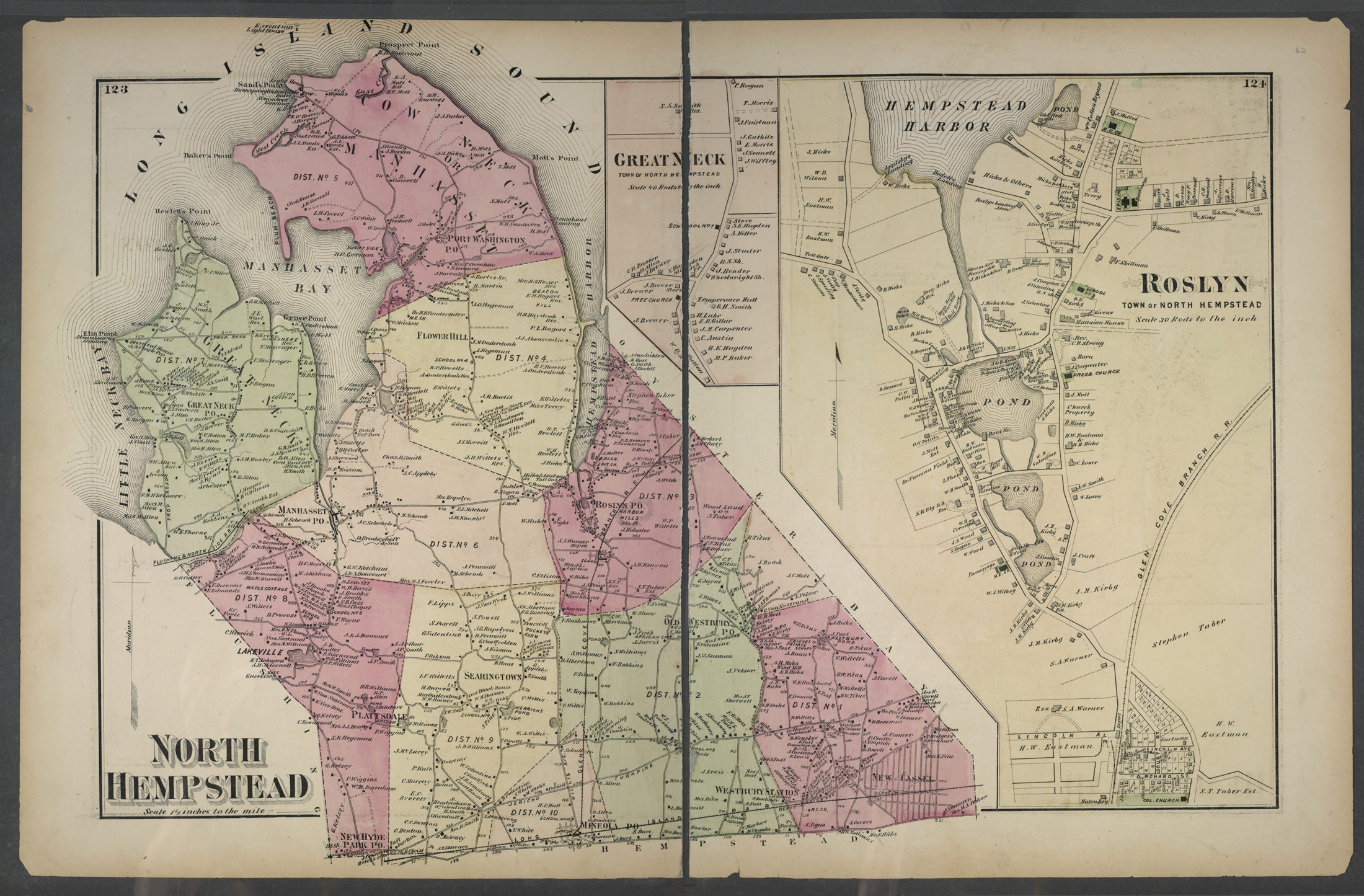

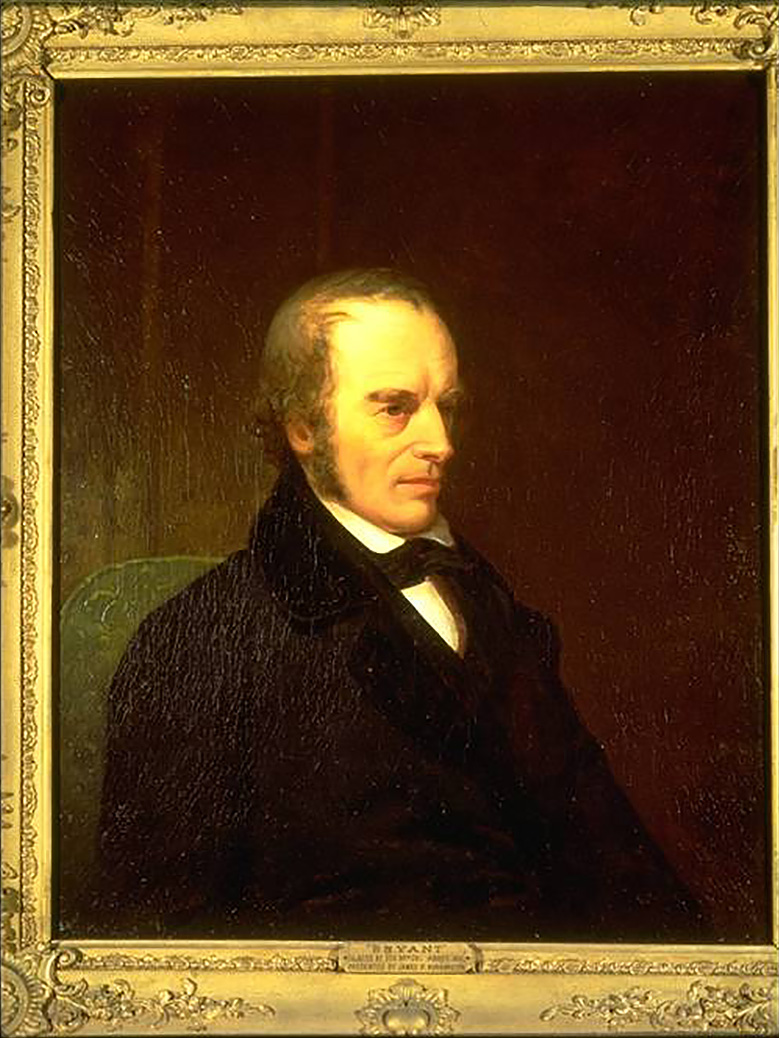

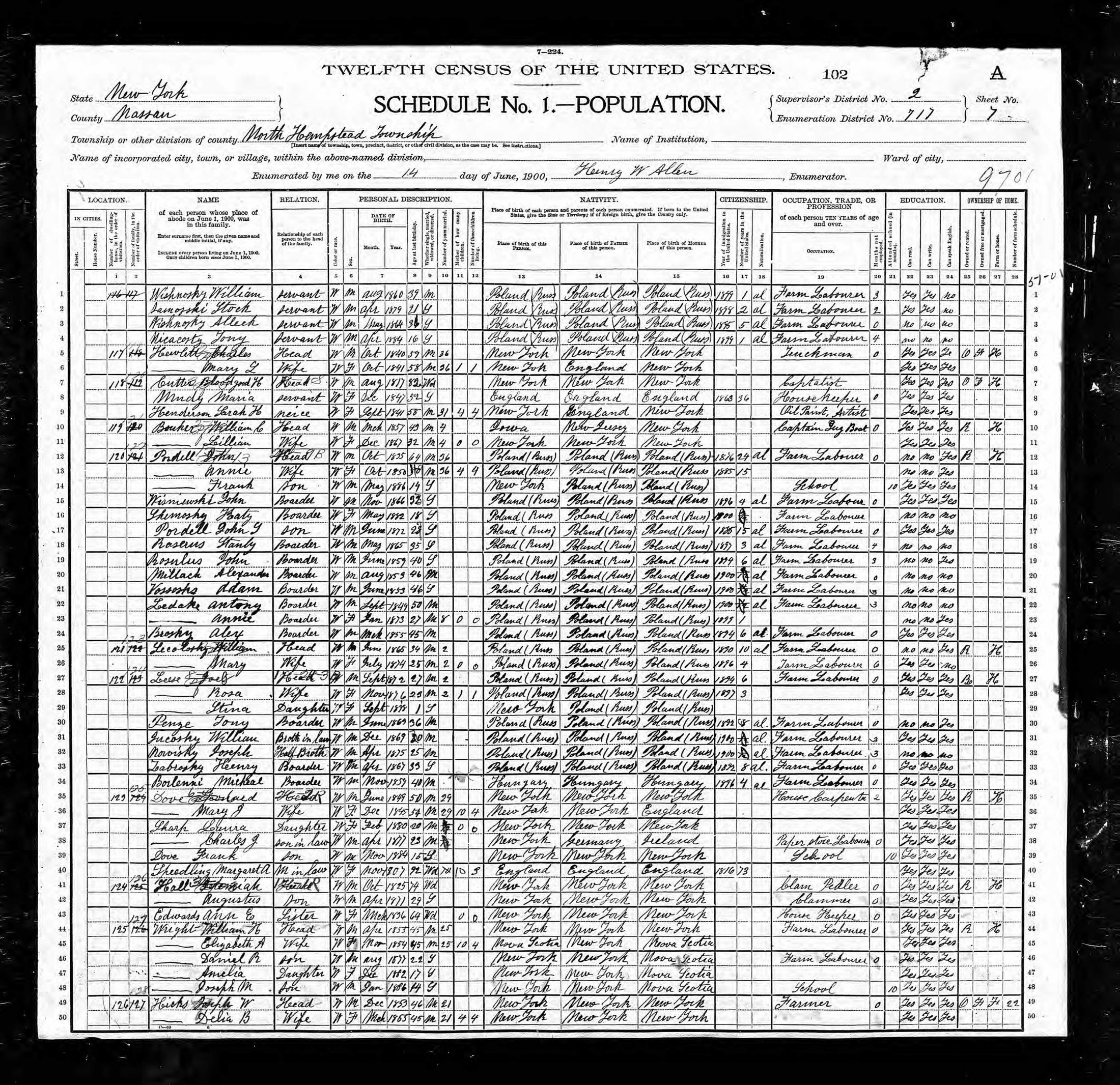

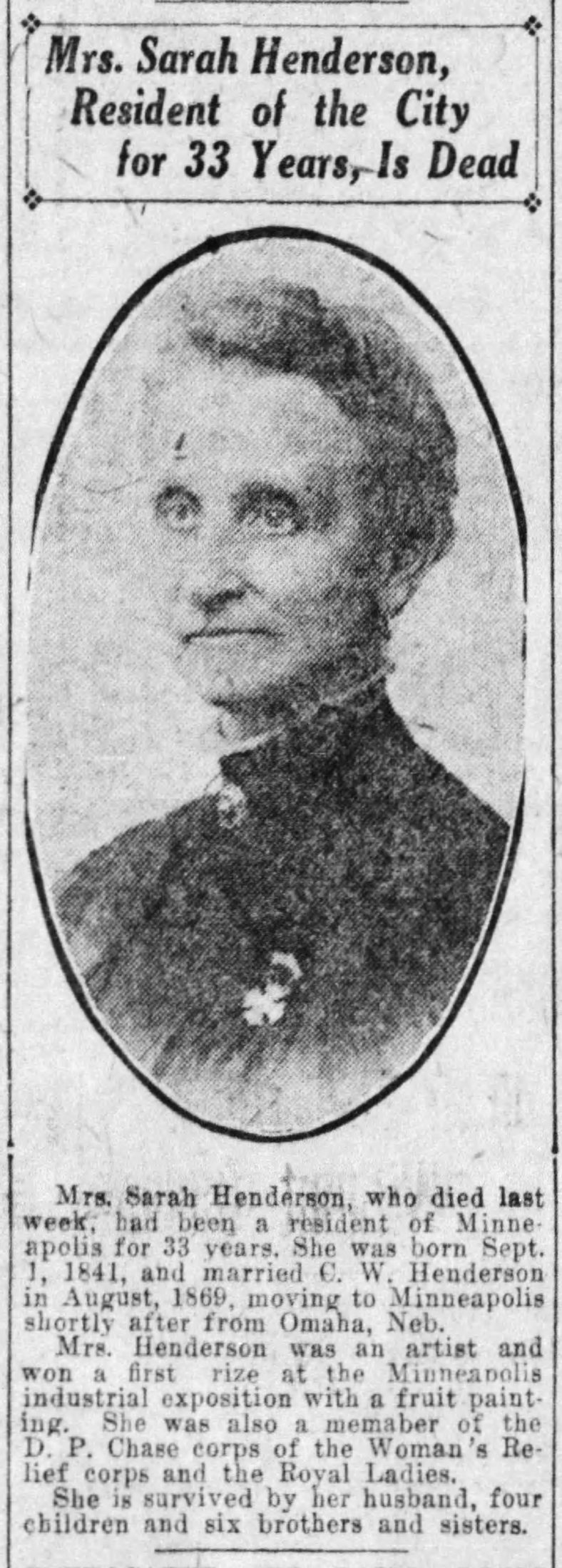

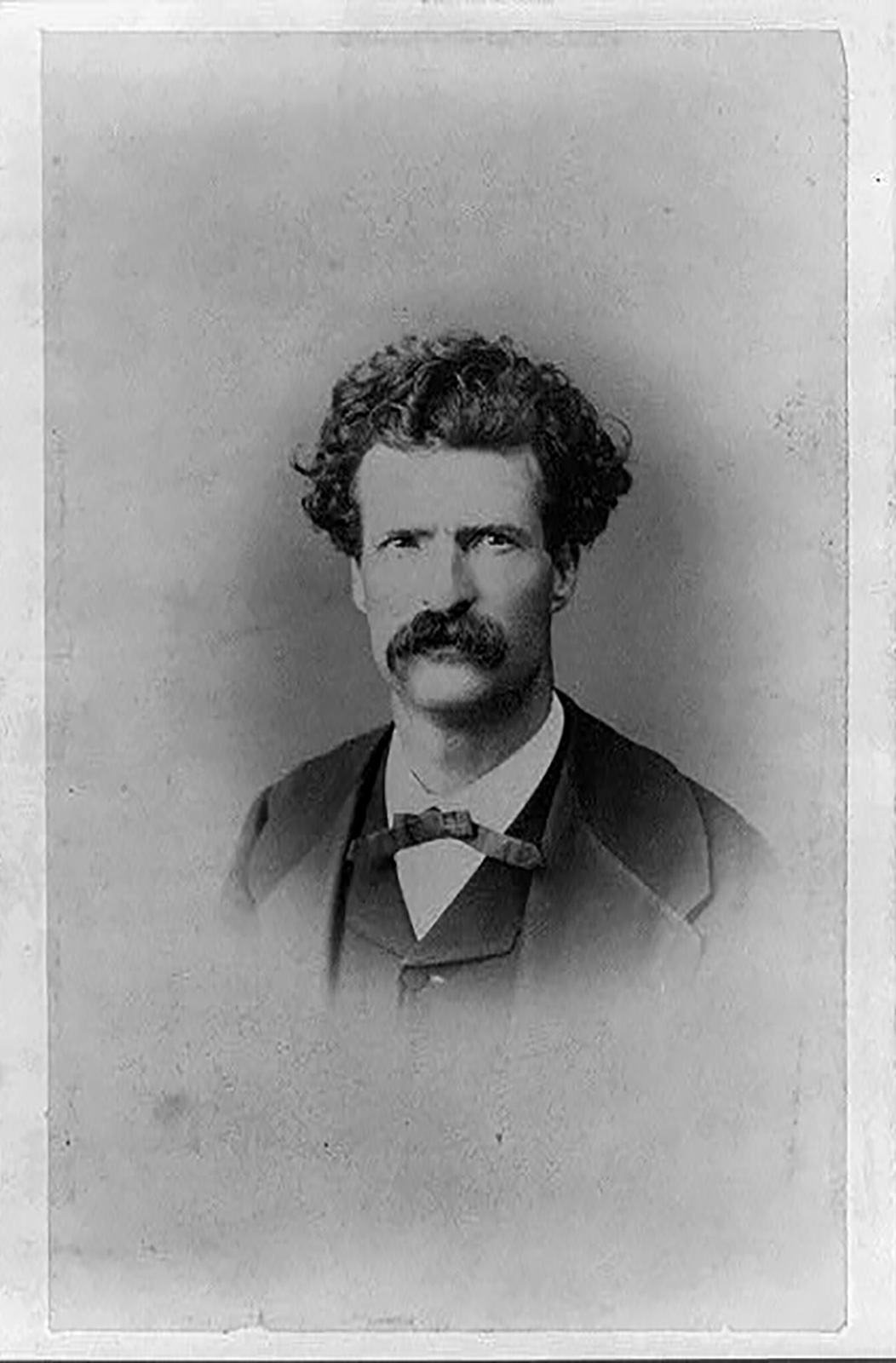

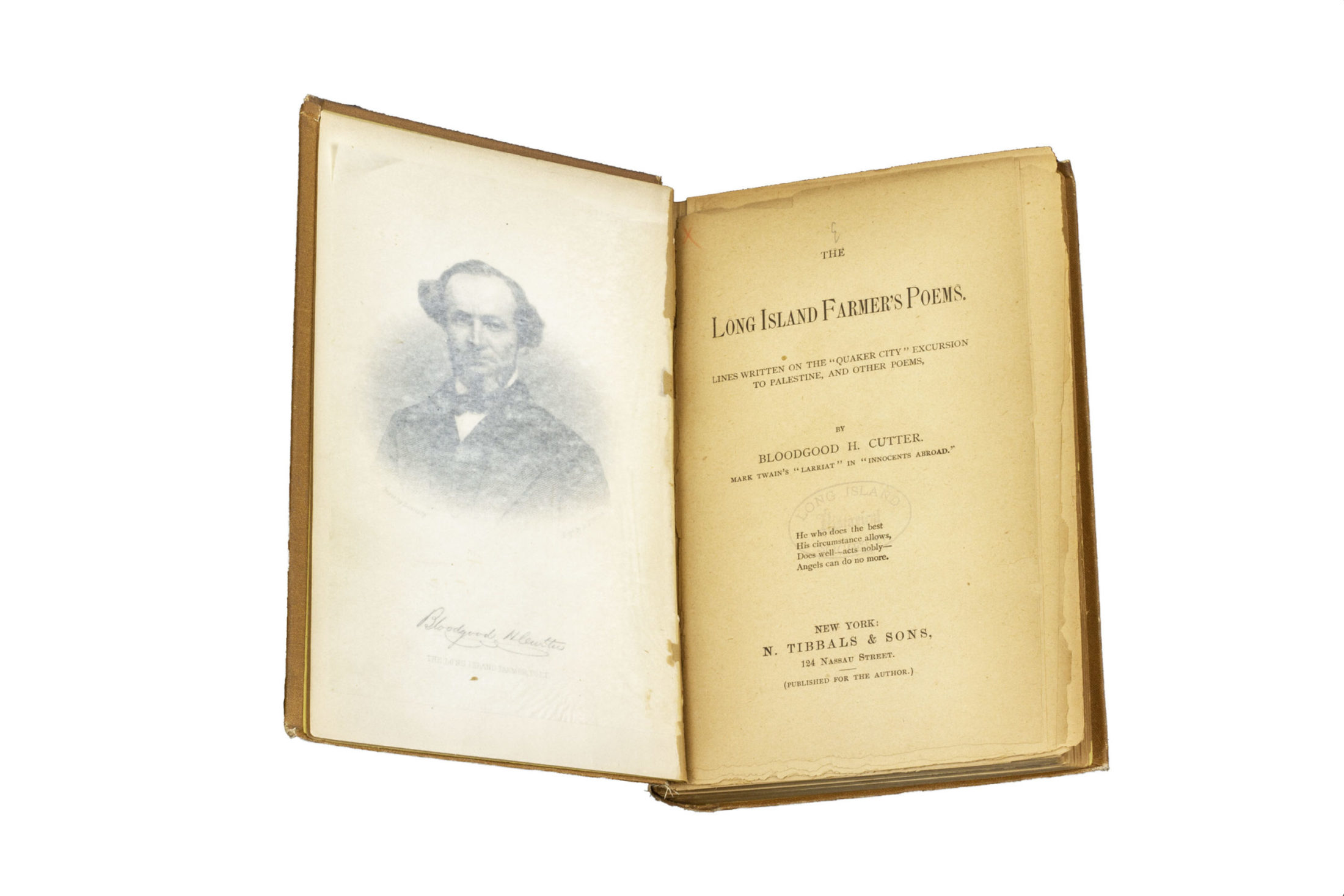

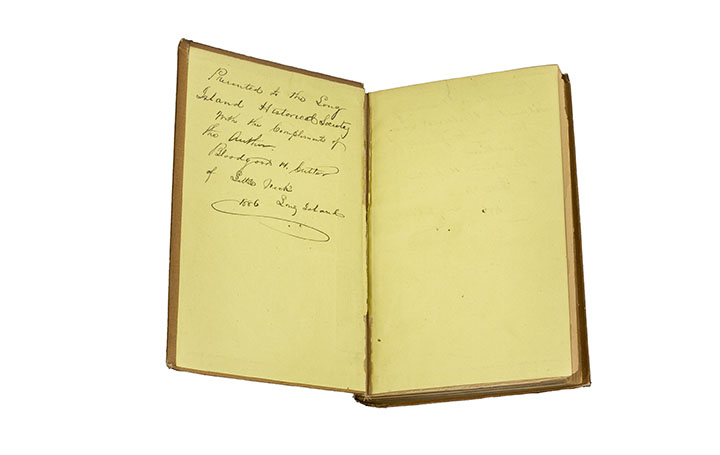

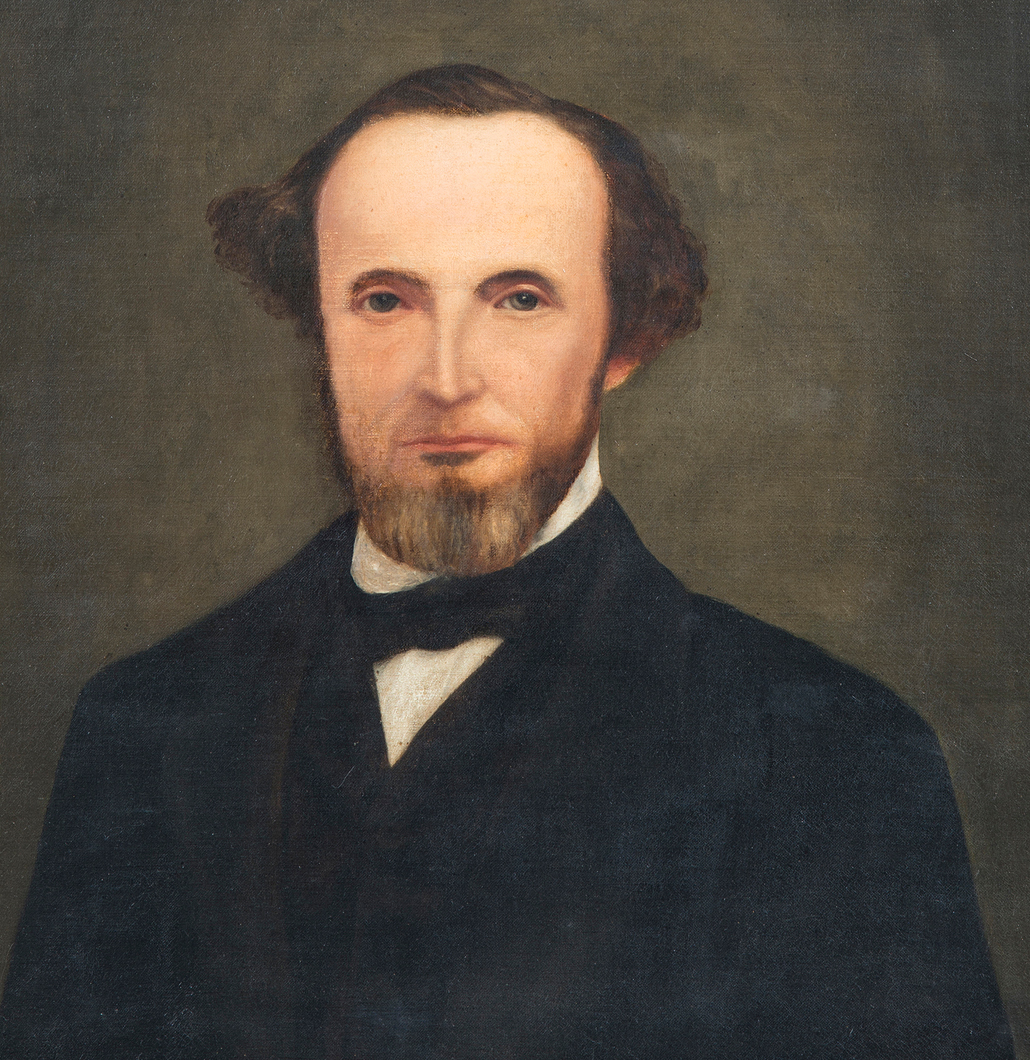

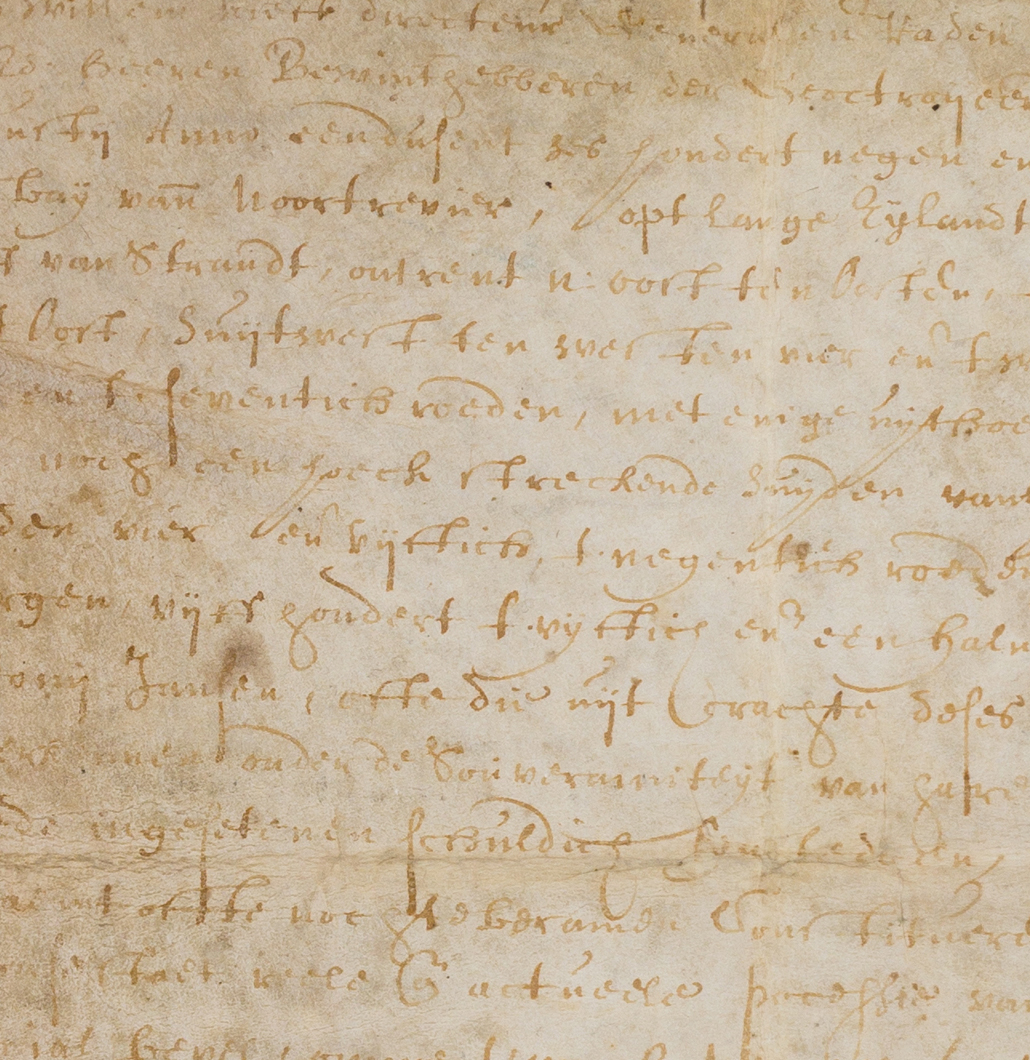

Bloodgood Haviland Cutter was the descendant on both sides of his family from some of Queens County’s earliest European settlers, granted land in the region in the 1600s by Dutch governor Willem Kieft. When the English government formally incorporated Queens County in 1683, it was home to five small townships: Newtown, Flushing, Jamaica, Hempstead, and Oyster Bay. Like the rest of Long Island, Queens was sparsely populated and its economy centered on farming and agriculture driven by enslaved workers. In 1790, less than 5,400 people lived in Queens, including 1,095 enslaved people.

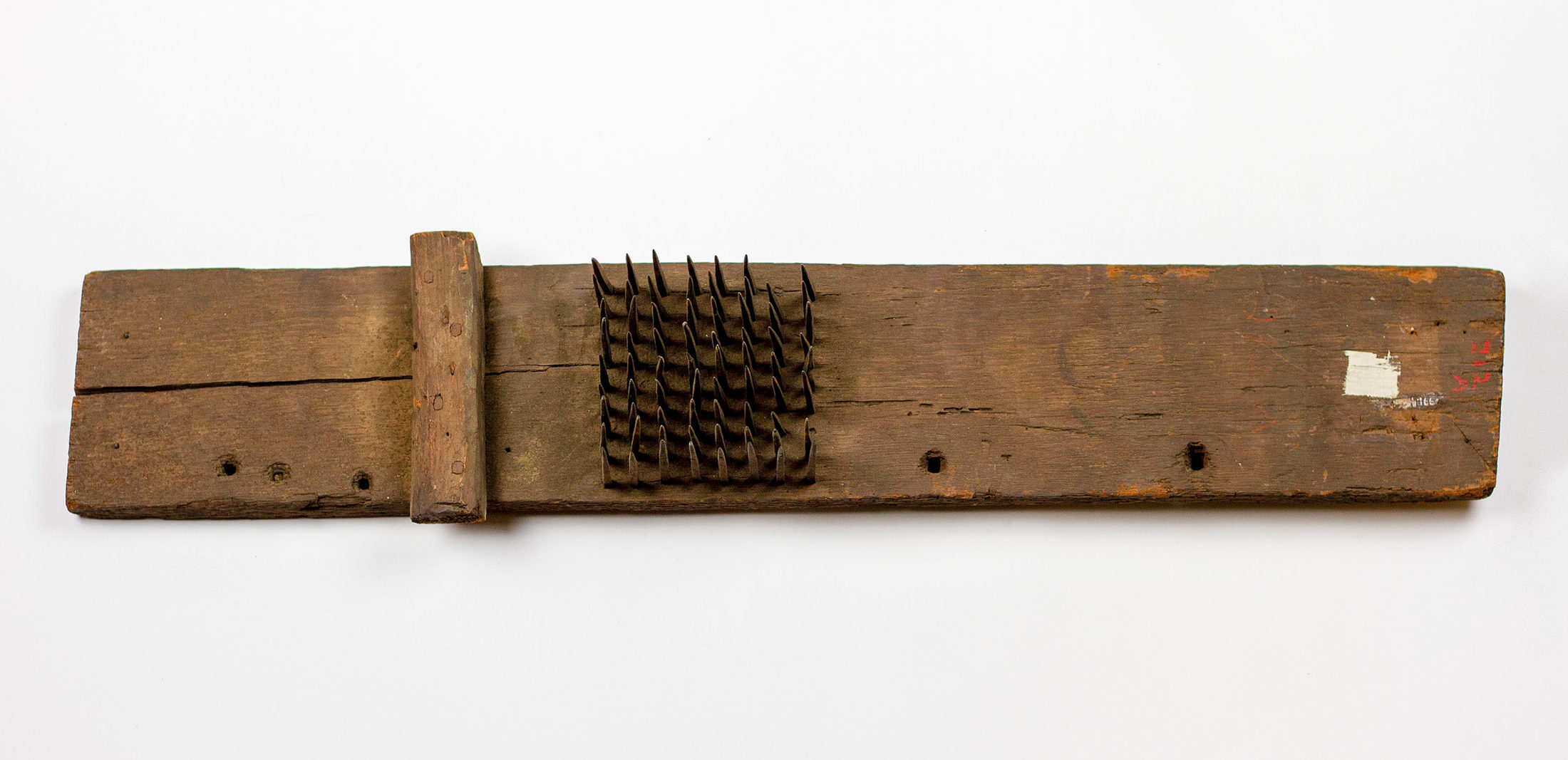

Hatchel, 18th century

Made in Newtown, Queens County, Long Island

M1991.456.1

Brooklyn Historical Society

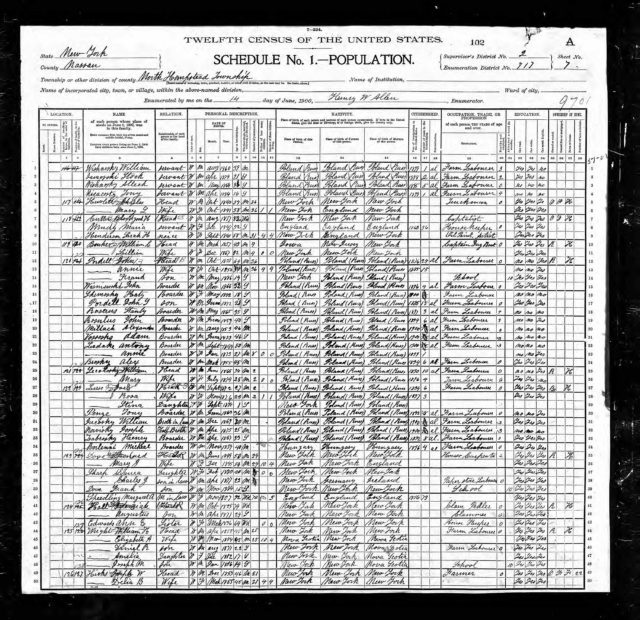

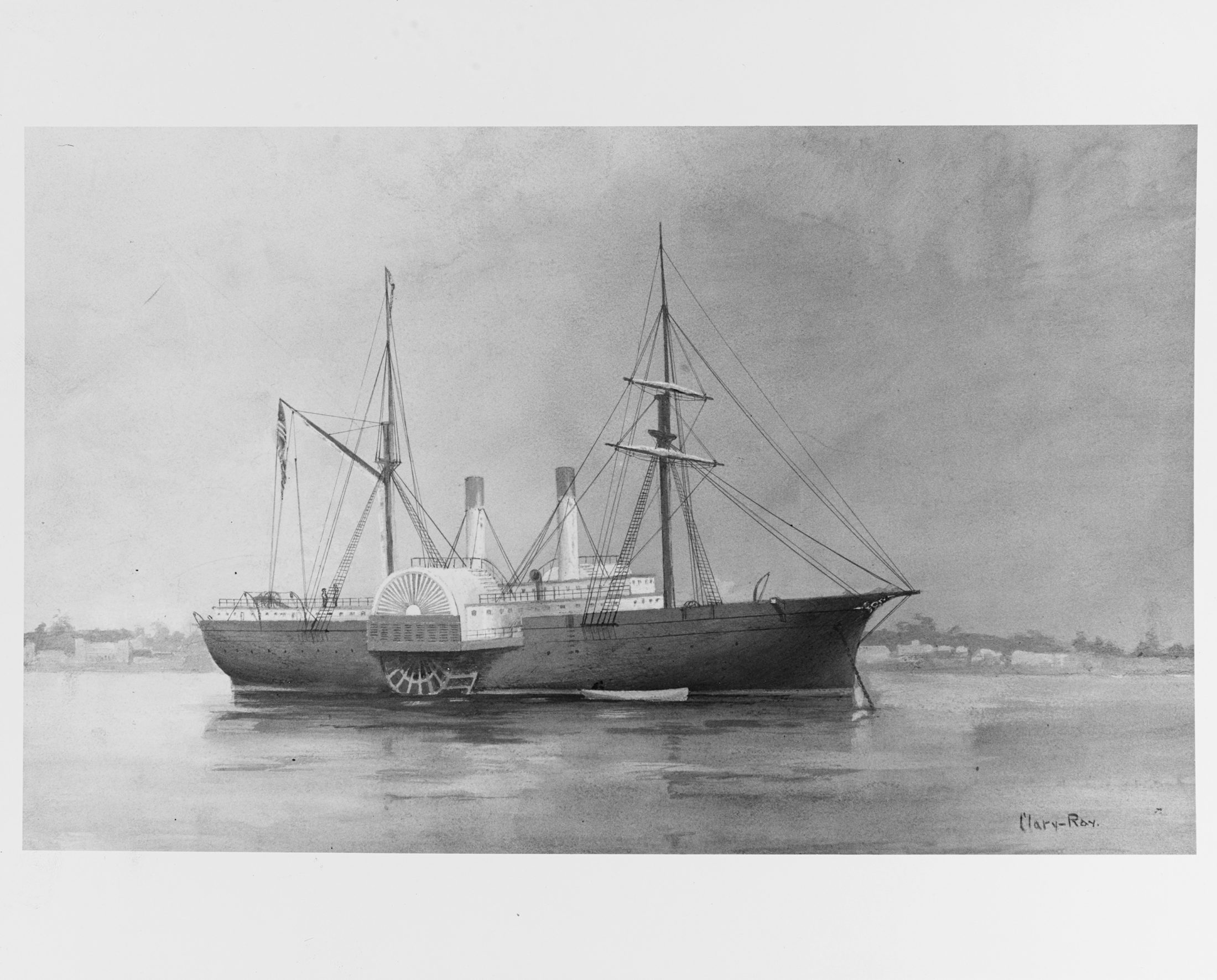

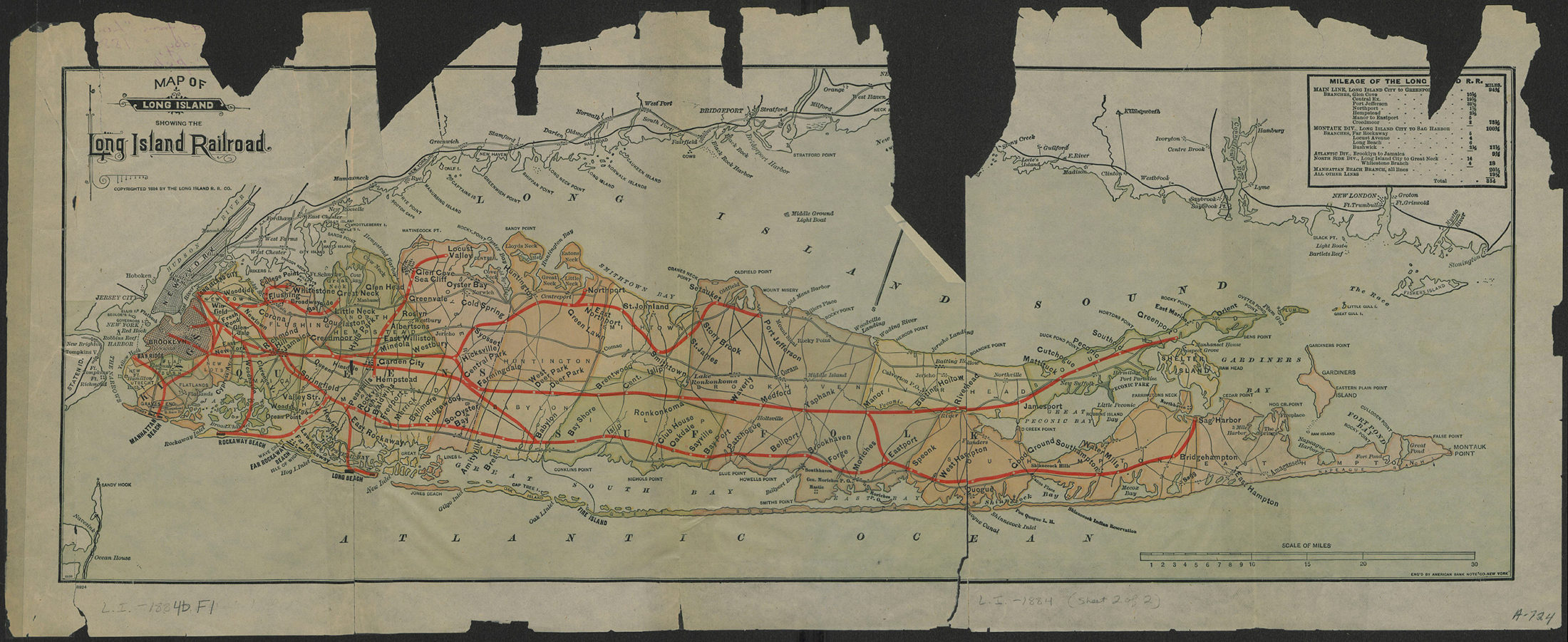

Queens remained largely rural well into the 1800s, but the introduction of railroads jump-started its transformation. The first tracks of the Long Island Railroad were laid in 1836 and connected Brooklyn to Jamaica, Queens. In the next decades, competing railroad corporations pushed rail lines farther east onto Long Island.

Map of Long Island showing the Long Island Railroad, 1884

Long Island Rail Road American Bank Note Company

L.I.-1884b.Fl

Brooklyn Historical Society

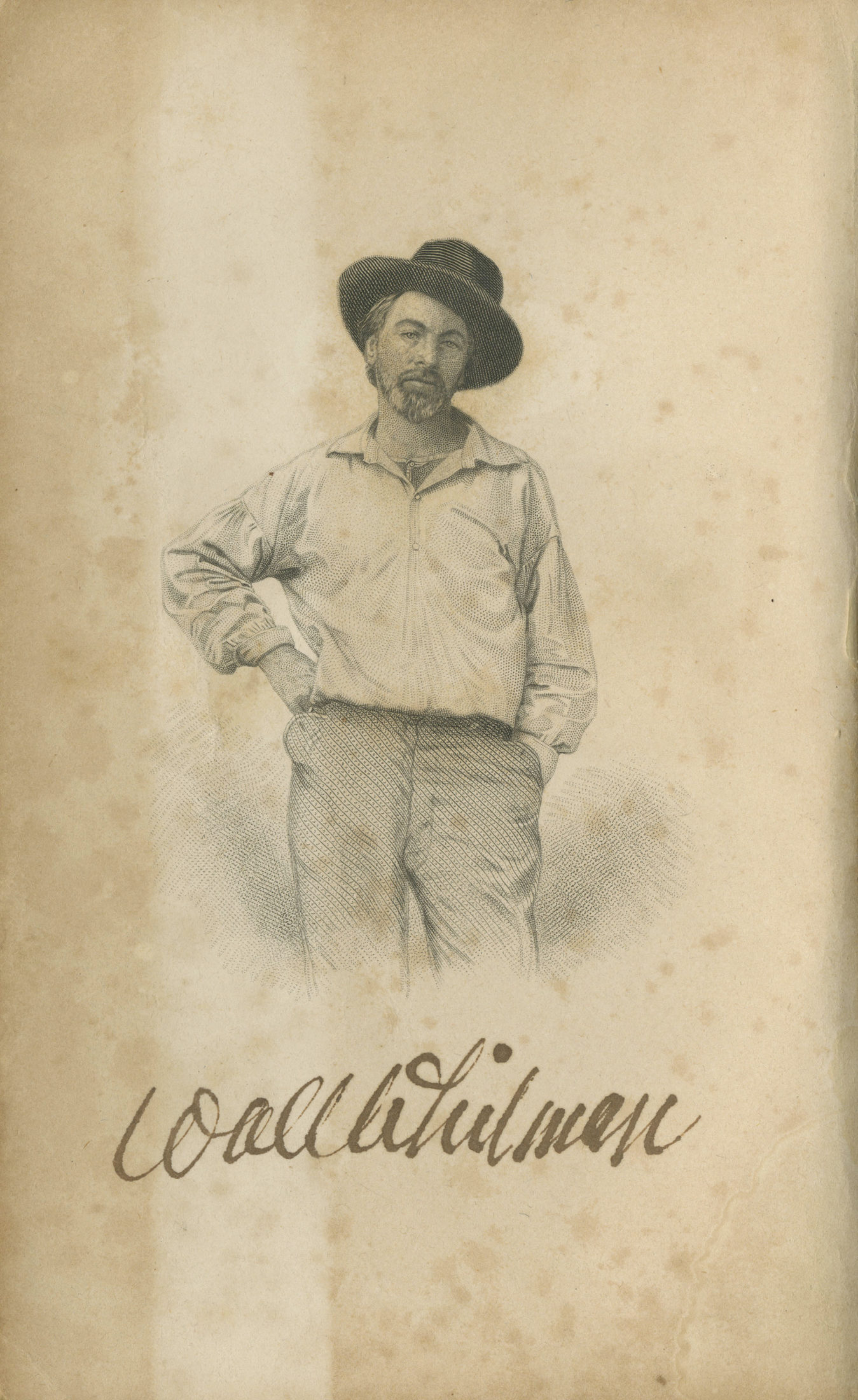

Cutter’s poetic musings provide evidence of his avid interest in railroads. He invested in several, including the Long Island Rail Road Company and the North Shore Railroad Company, the latter organized in 1863 to build tracks east from Flushing towards Great Neck. In his poem “North Side Railroad,” Cutter enthusiastically cried out:

Come out, my friends, and now subscribe

To build a road on the North Side,

If each will only do his part,

We soon will see the railroad start.

Port Jefferson Rail Road Station, 1878

George B. Brainerd

V1972.1.197

Brooklyn Historical Society

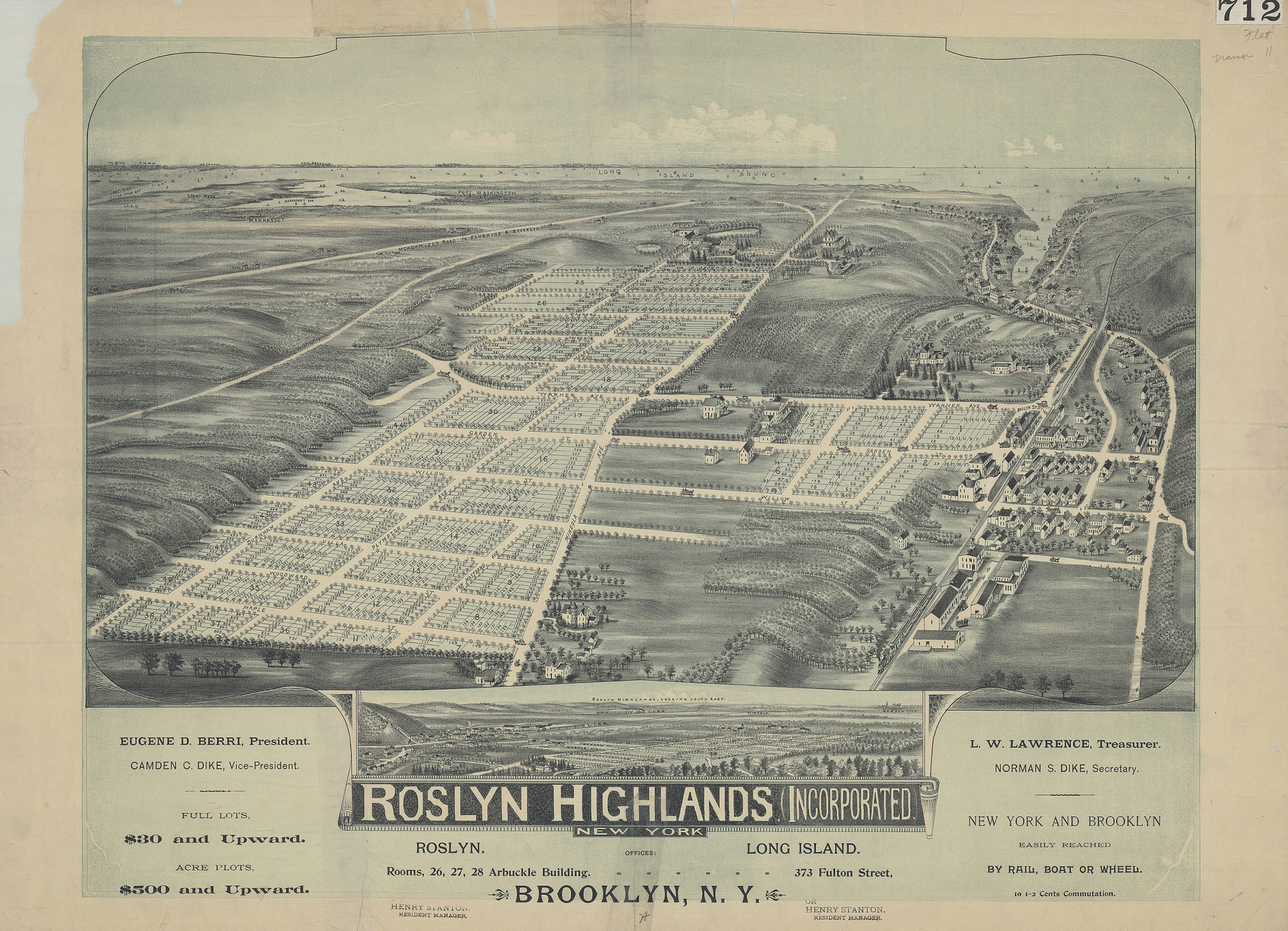

Improved transportation options in the second half of the 1800s led to a boom in land speculation in Queens and the construction of new communities. Many new residents were attracted to Queens because they were searching for a suburban retreat from the growing congestion of New York City.

Roslyn Highlands Incorporated, New York, after 1892

L.I.-[189-?]a.Fl

Brooklyn Historical Society

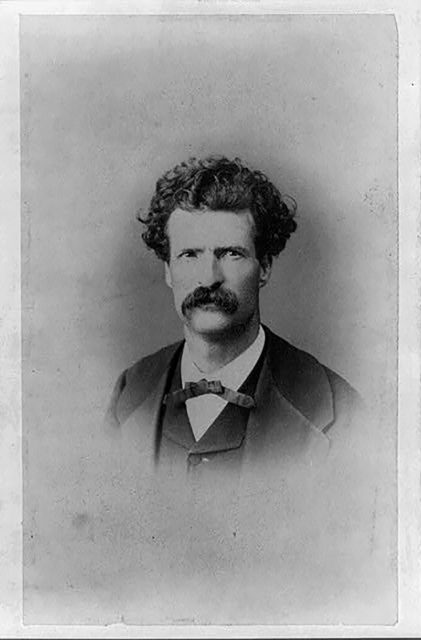

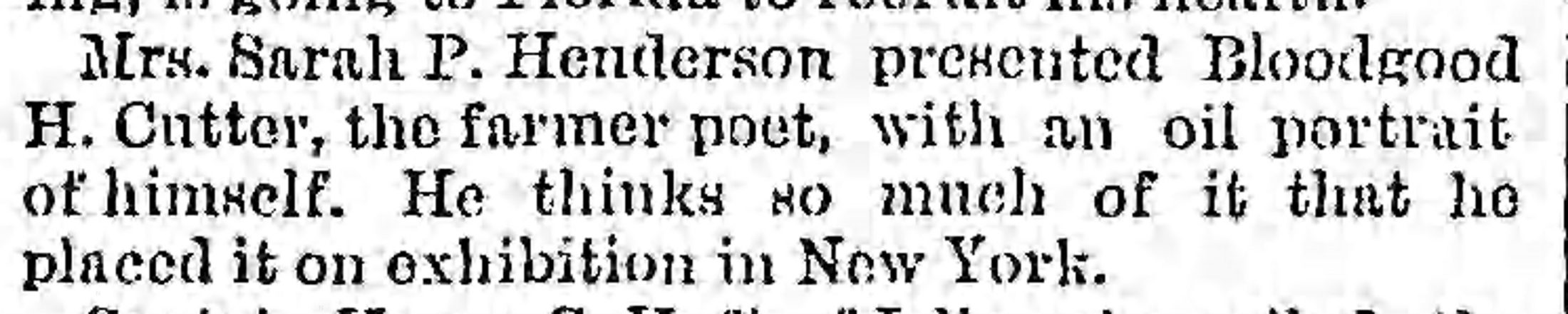

While Bloodgood Cutter’s quaint “Long Island Farmer Poet” image contradicts his status as a shrewd venture capitalist who increased his wealth by investing strategically. In his poem “North Side Railroad,” Cutter summed up the risk and rewards of investing in Long Island’s railroads.

Our land will then take such a rise,

‘Twill us agreeably surprise…Then citizens will out remove,

And then the North Side will improve;

How much better that will pay,

Then raising either corn or hay.Then if you wish to sell your land,

Can get the chink right in your hand;

And then if you desire more ease;

Can work or play, just as you please.