Why Are There So Few Great Female Artists?

Discovering Sarah Purchase Henderson, Bloodgood Cutter’s portraitist

This portrait arrived at the Long Island Historical Society without much recorded information. It likely joined the LIHS collection after Cutter died in 1906, when the contents of his Little Neck, Queens, estate sold at auction. The identity of the portraitist, “S. Henderson,” documented on the lower right corner of the canvas, has long been a mystery. We now know that the portrait’s painter was related to Bloodgood Cutter, and a woman.

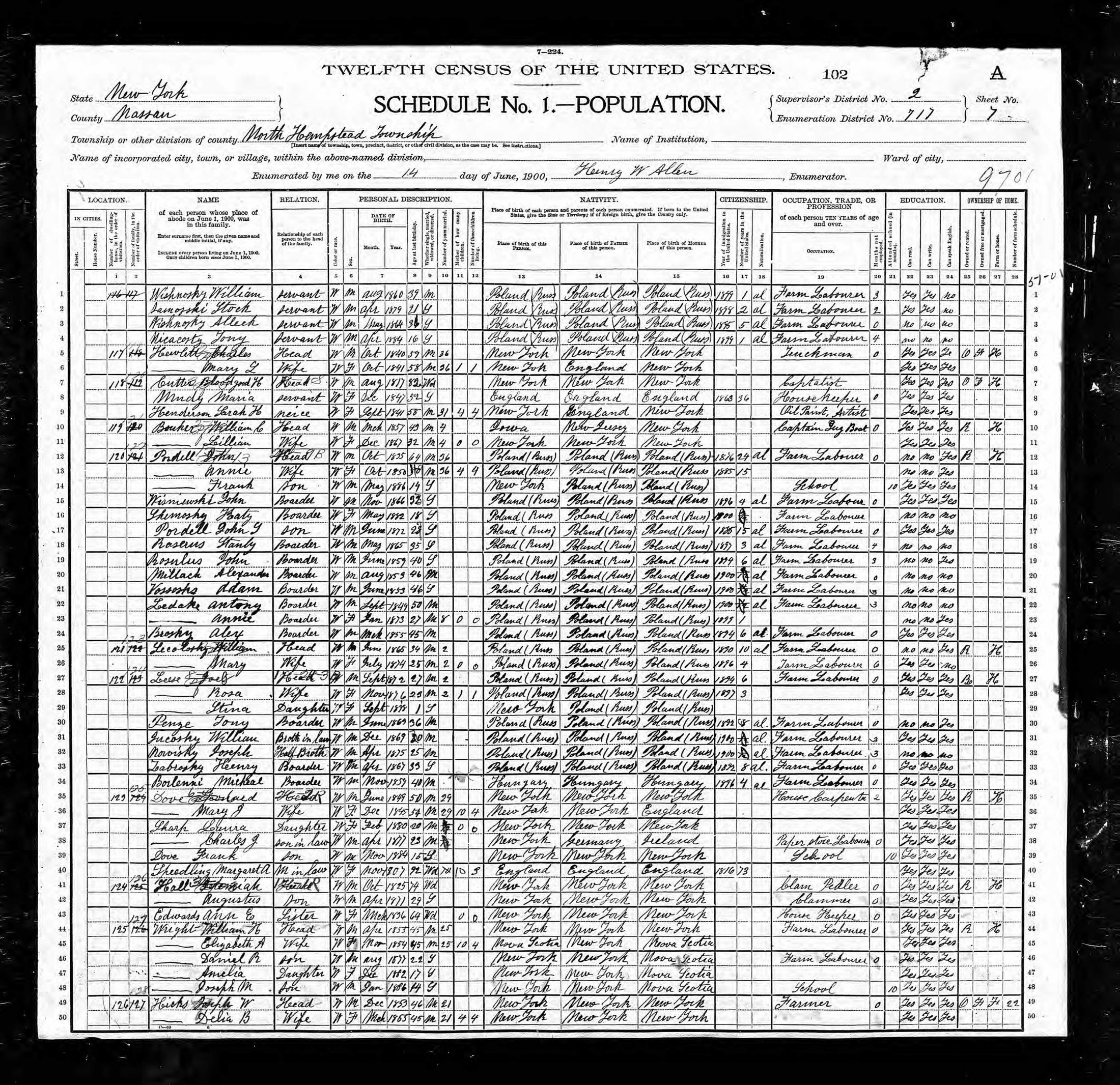

Federal census for Bloodgood Cutter, 1900

United States Census Bureau

National Archives and Records Administration

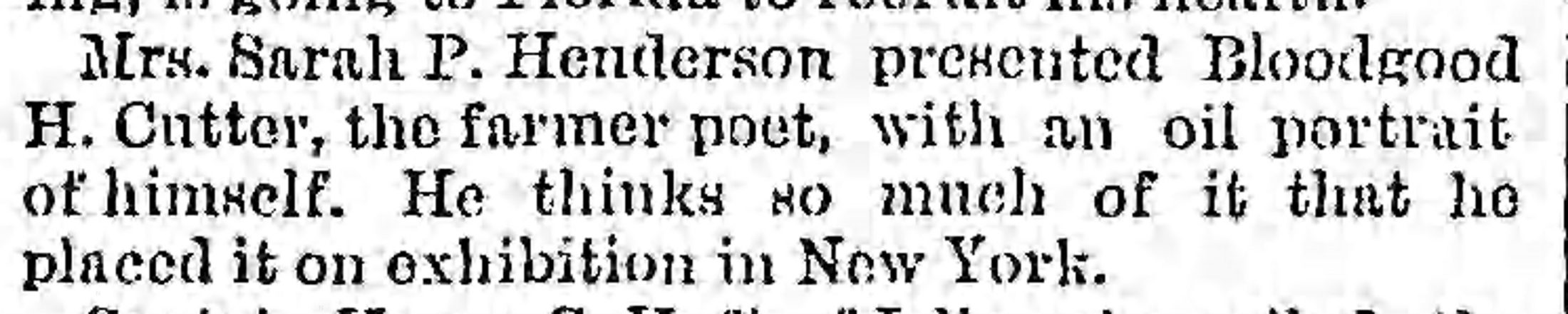

Cutter had no children of his own, but he did have many nephews and nieces, including Sarah Purchase Henderson. In 1900, Sarah was staying with her uncle and appeared in the federal census with “oil paint artist” listed as her profession. Following this trail revealed Henderson to be the painter of this portrait, as evidenced by a Brooklyn Daily Eagle article from 1888 announcing that she had “presented Bloodgood Cutter, the farmer poet, with an oil portrait of himself.”

“Down on Long Island”

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 25, 1888

Brooklyn Public Library

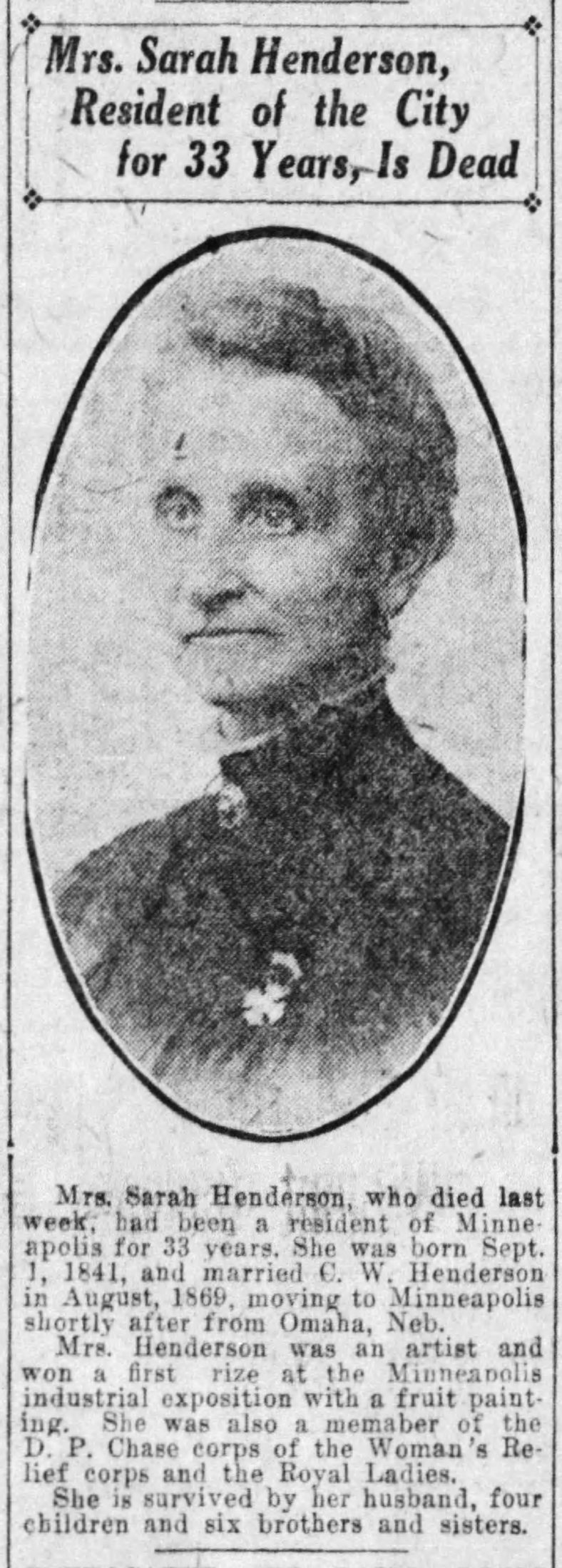

Like many female artists in the 1700s and 1800s, Henderson likely struggled to find a place for herself within the male-dominated profession. Although women artists did join professional organizations like the National Academy of Design and Brooklyn Art League and exhibited their works, all too often they were dismissed as “accomplished” amateurs.

“Mrs. Sarah Henderson, Resident of the City for 33 Years, is Dead”

Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 18, 1914

Despite this, women artists like Henderson pursued their passions, seeking training and opportunity domestically and abroad. Today, the lives and talents of female artists are being rediscovered. Like Sarah Henderson’s portrait of her uncle, other paintings at BHS previously unattributed are being rediscovered as the work of local female artists, including Brooklynite Eleanor C. Bannister (1858-1939) and portraitist Susan Mary (S.M.) Norton (1855-1922).

Joshua Marsden Van Cott, Jr., 1891

Susan Mary Norton

M1974.241.1

Brooklyn Historical Society

When Henderson painted this portrait of her Uncle Bloodgood in 1888, he was seventy-one years old, far older than he appears in her idealized representation of him. Evidence shows that Henderson likely based her painting on a photograph of her uncle taken in the 1860s, immortalizing him in his prime. The portrait then reflects Bloodgood Cutter’s ideas about his legacy, which he recorded in a poem, “On Seeing His Own Likeness.”

My friends, this likeness of my mortal form,

Preserve as a keep-sake when I am gone;

That is, when death lays low my weary head,

And consigns me to mansions of the dead.Then my lines, though they may be rude in kind,

Will represent the inner man, or mind

And by using my simple pen—

Indite those for myself, and fellow-men.