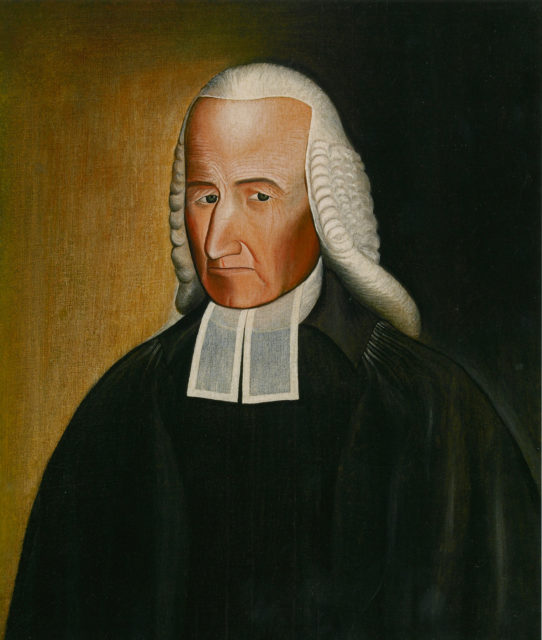

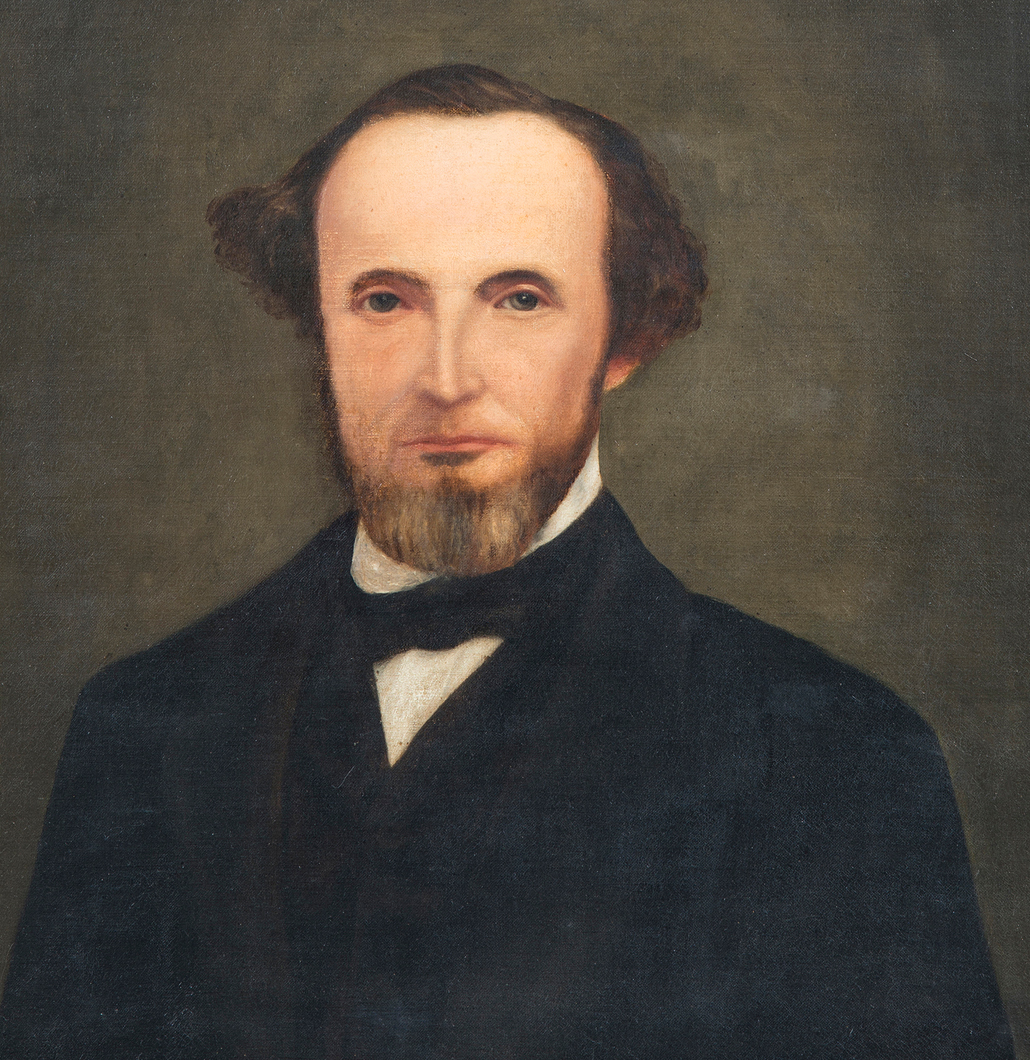

Abraham G.D. Tuthill

A Rural Long Island Portrait Painter

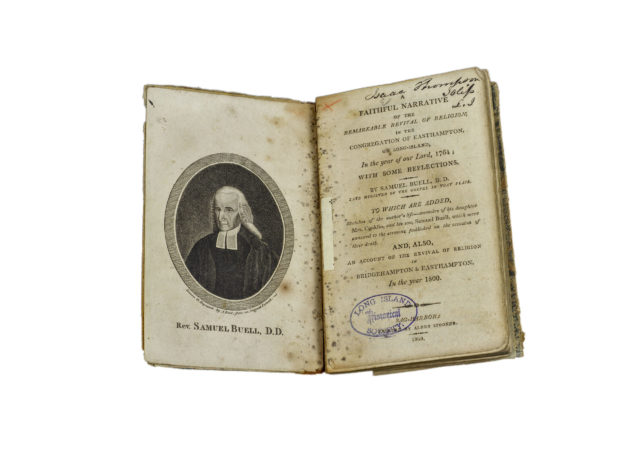

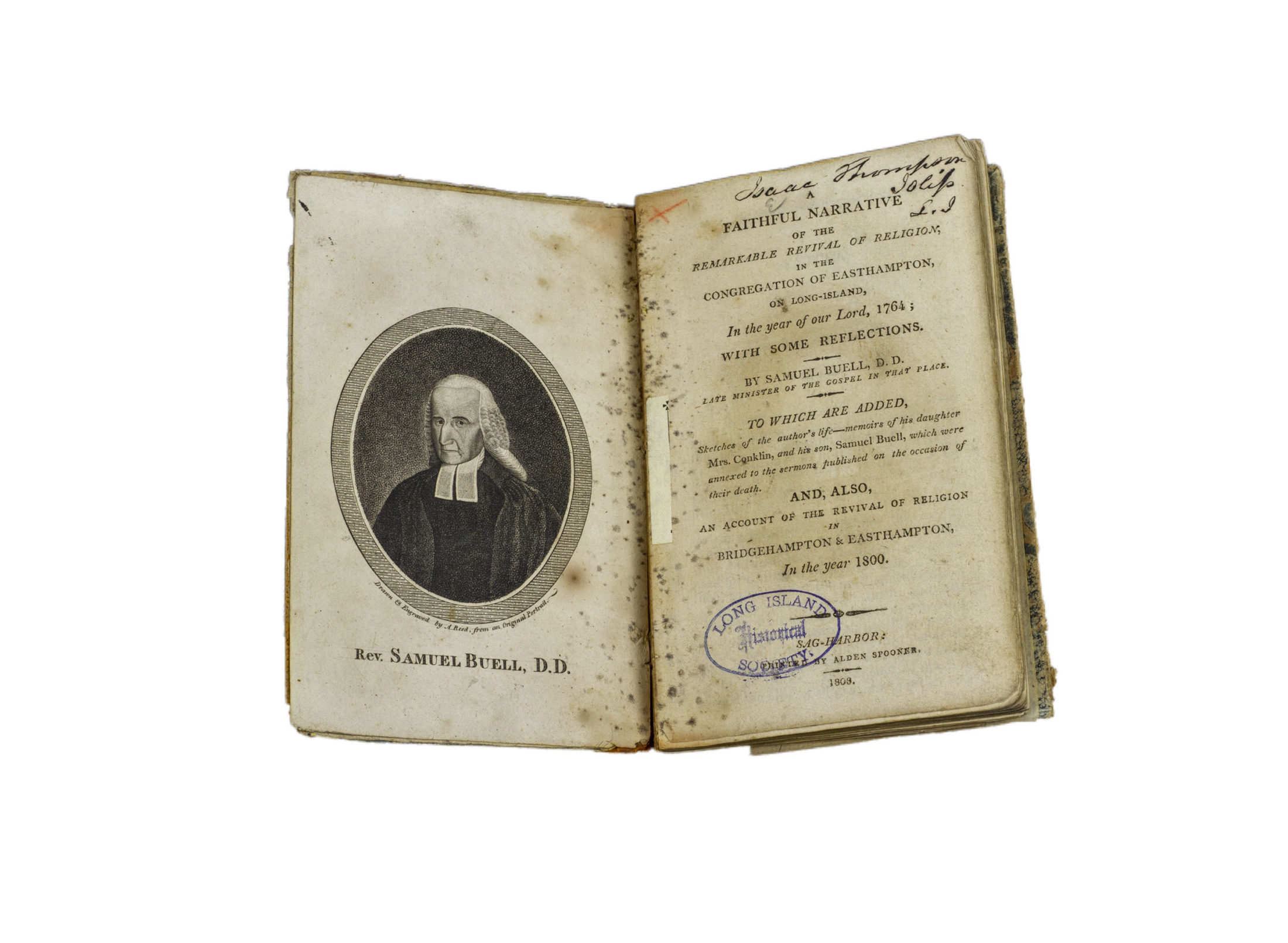

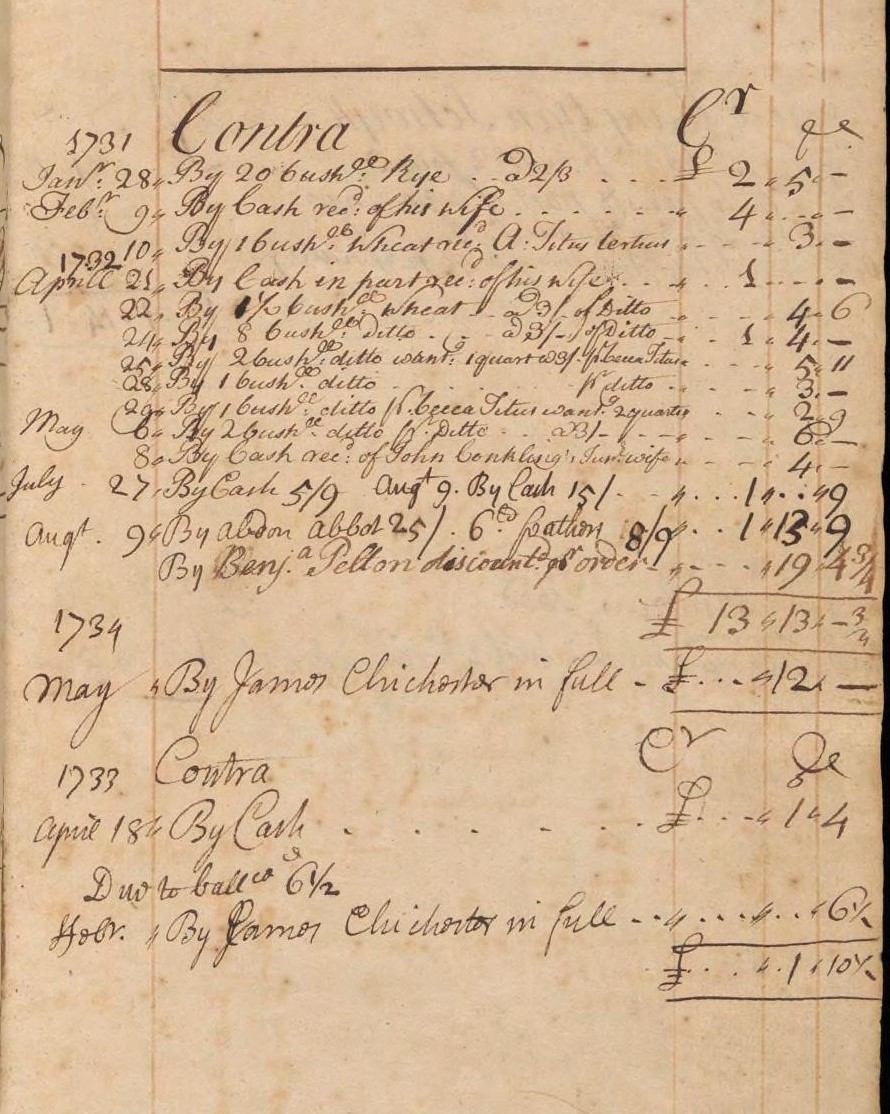

A small-town Long Island artist with big ambitions, Abraham Guilielmus Dominey Tuthill had a career typical among early America’s working artists. Born at Oyster Ponds on the North Fork of Suffolk County in 1777, at the start of his career in his early twenties, Tuthill did not have access to formal training. However, his ability to produce competent and sensitive portraits endeared him to Suffolk County’s affluent families. His early portraits, including Buell’s and one of Joanna Conklin Gardiner (1745–1809), ultimately brought Tuthill to the attention of Colonel Sylvester Dering of Shelter Island, who sponsored Tuthill’s professional artistic training.

Joanna Conklin Gardiner, 1799

Abraham G.D. Tuthill

Collection of the Oysterponds Historical Society

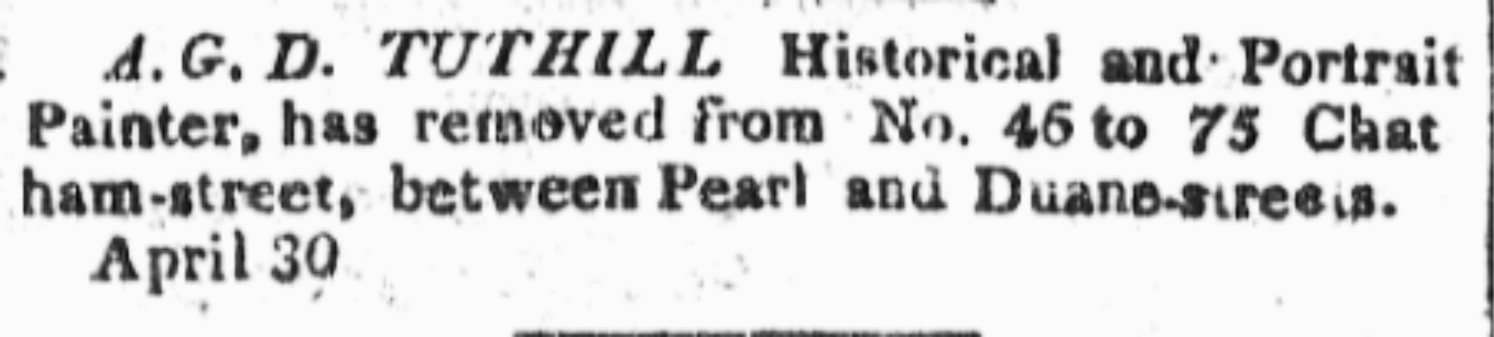

American artists looked to Europe to hone their artistic abilities at the turn of the 1800s. Tuthill traveled from New York City to London, where he spent the next eight years studying and improving his painting skills. By 1811, he had returned to the United States and established a studio on Chatham Street in New York City, where he encountered American art critic William Dunlap. Known as America’s first art historian, Dunlap later wrote that although Tuthill “told me that he had been to London to study the art…his works bore little indication of that school.”

A.G.D. Tuthill Advertisement

The New York Columbian, May 4, 1811

Despite his sarcastic criticisms, Dunlap attested that Tuthill later achieved relative success as an itinerant artist. While America’s early art world was centered in its growing urban cities, people living in rural areas still wanted portraits to hang in their homes as proof of their respectability. By traveling to more rural areas such as upstate New York, Michigan, Vermont, and Ohio—where artists were scarce and demand for portraits was high—Tuthill made a steady living well into the 1830s. He died in 1843 in Montpelier, Vermont.

Examples of Tuthill’s work are scattered throughout museum collections in the Northeast and Midwest, a testament to a determined artist’s career kickstarted by the early commissions and support of Long Island families like the Buells.

Melancthon Taylor Woolsey, circa 1820

Abraham G.D. Tuthill

1954.107

New-York Historical Society