Christianity and Race on Long Island

Samuel Buell and Samson Occum

The Reverend Samuel Buell encouraged ongoing efforts to convert local American Indian tribes to Christianity. This brought him into contact with one of eighteenth-century Long Island’s most complex religious leaders, Samson Occum (1723–1792), a Mohegan Indian Christian convert.

Early historians described Occum as “a heathen reformed,” an example of what they believed to be the civilizing powers of Christianity on the country’s American Indian population. Today, historians view Occum as a man caught between two worlds. While he voluntarily converted to Christianity and became a preacher, Occum was also a tribal leader and a vocal advocate for the rights of American Indians, who then faced systematic dispossession of their ancestral lands throughout the Northeast.

Seen through Occum’s eyes, eighteenth-century Suffolk County history becomes a story of religion and community, and a window into the history of racial differences in America.

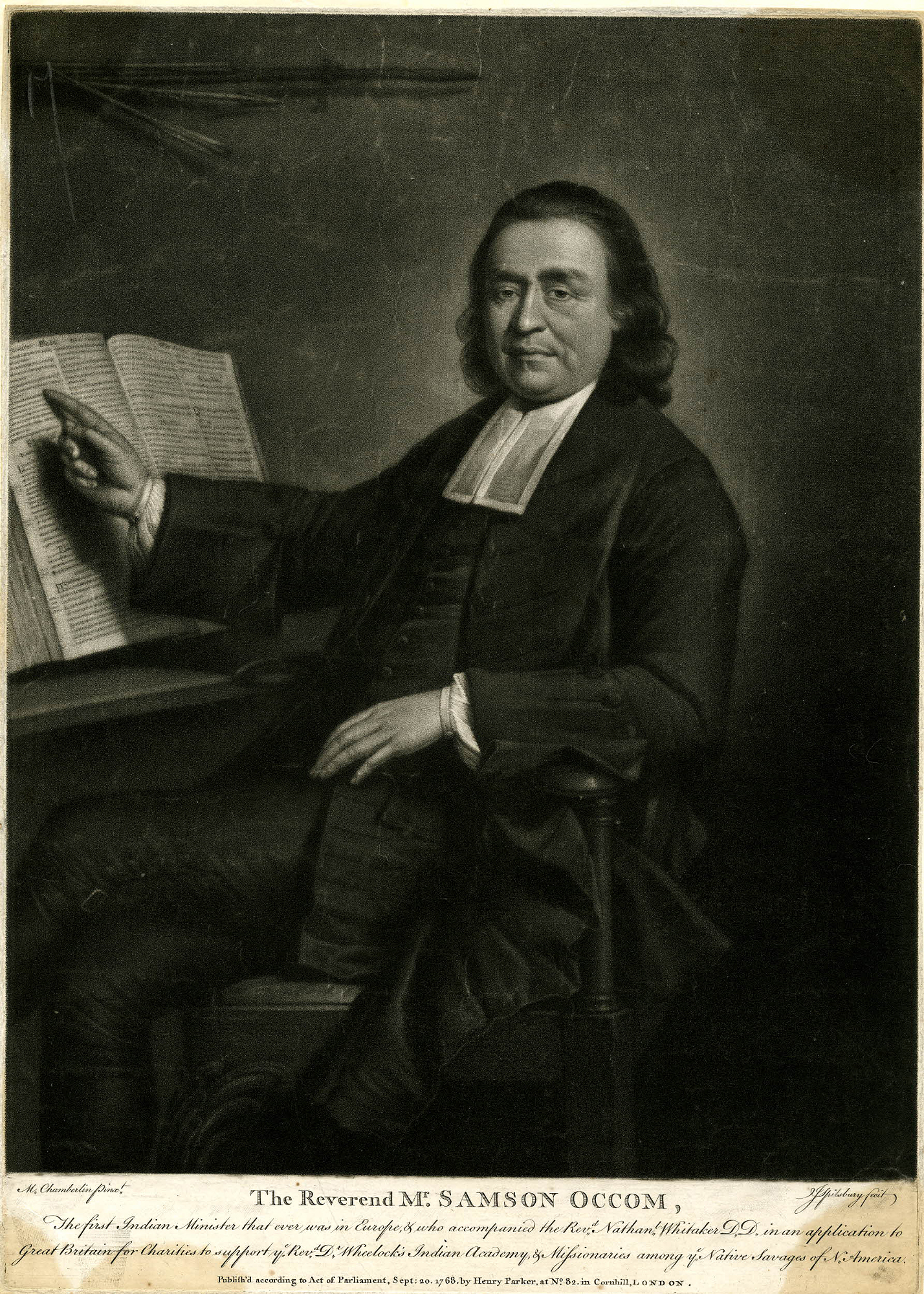

The Reverend Mr. Samson Occum, 1768

Henry Parker, London (publisher)

1902,1011,5130

The British Museum

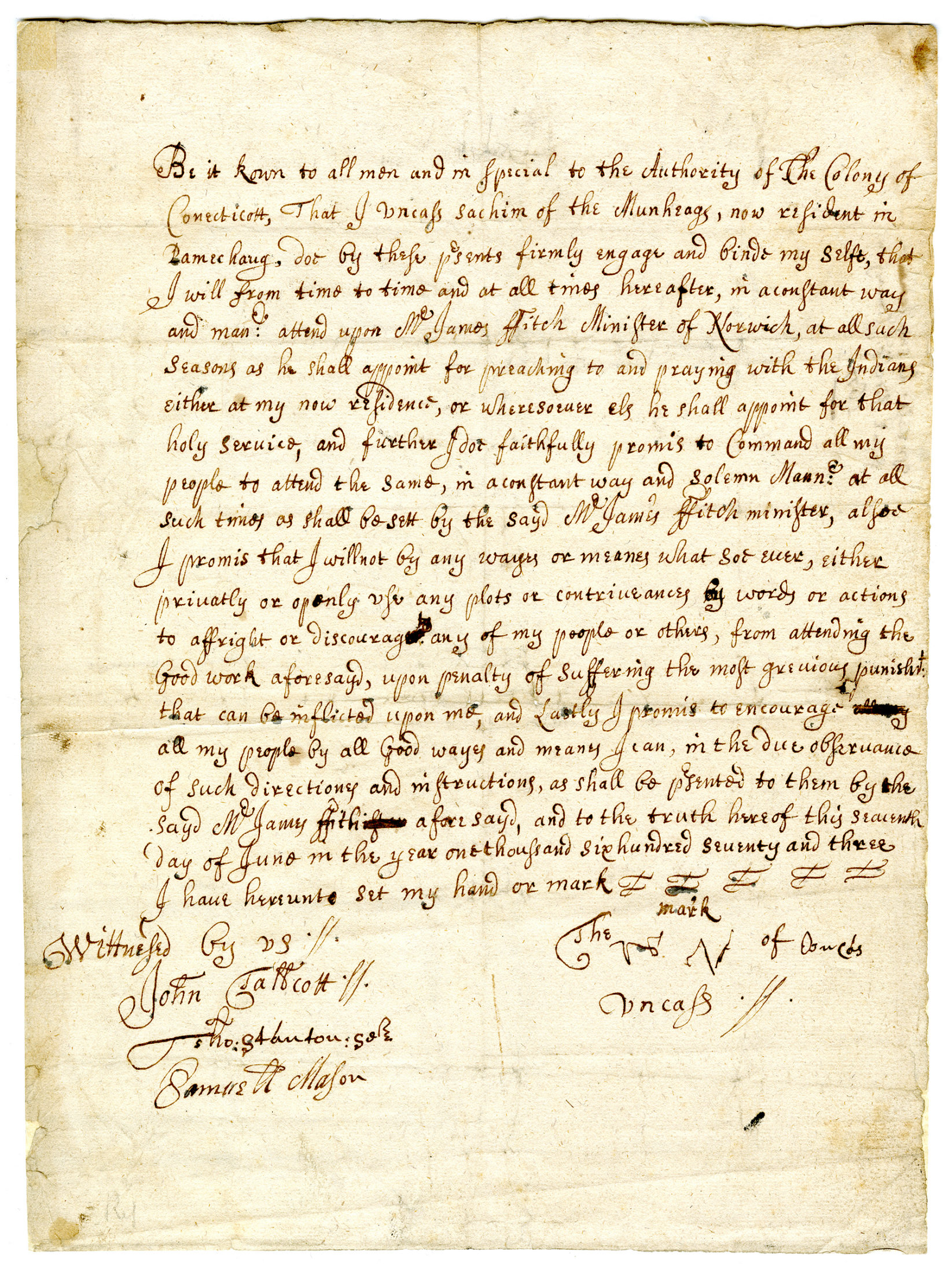

Samson Occum was born in Connecticut in 1723 into a Mohegan Indian community. For centuries, Christian missionaries had attempted to convert the Mohegans, to mixed results. Beginning in the mid-1600s, tribal leaders sought alliances with local English authorities to secure their peoples’ safety. These political negotiations sometimes required that preachers be allowed to spread Christian teachings, as did the 1673 contract in the BHS collection between the Mohegan tribal leader Sachem Uncas and Mr. James Fitch, minister of Norwich. While European preachers sought to “civilize” through Christianity, religion may have appealed to American Indians like Occum for the negotiating power it provided.

Contract between Uncas, sachem of the Mohegans, and James Fitch, minister of Norwich, 1673

Mid-Atlantic Early Manuscripts collection (1972.002)

Brooklyn Historical Society

Like Samuel Buell, Occum was swept up in the fervor of the Great Awakening as a teenager. Occum’s conversion and desire to learn brought him to the attention of Eleazar Wheelock, a Yale-educated minister who became Occum’s mentor and oversaw his education in English, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, in addition to ministerial studies.

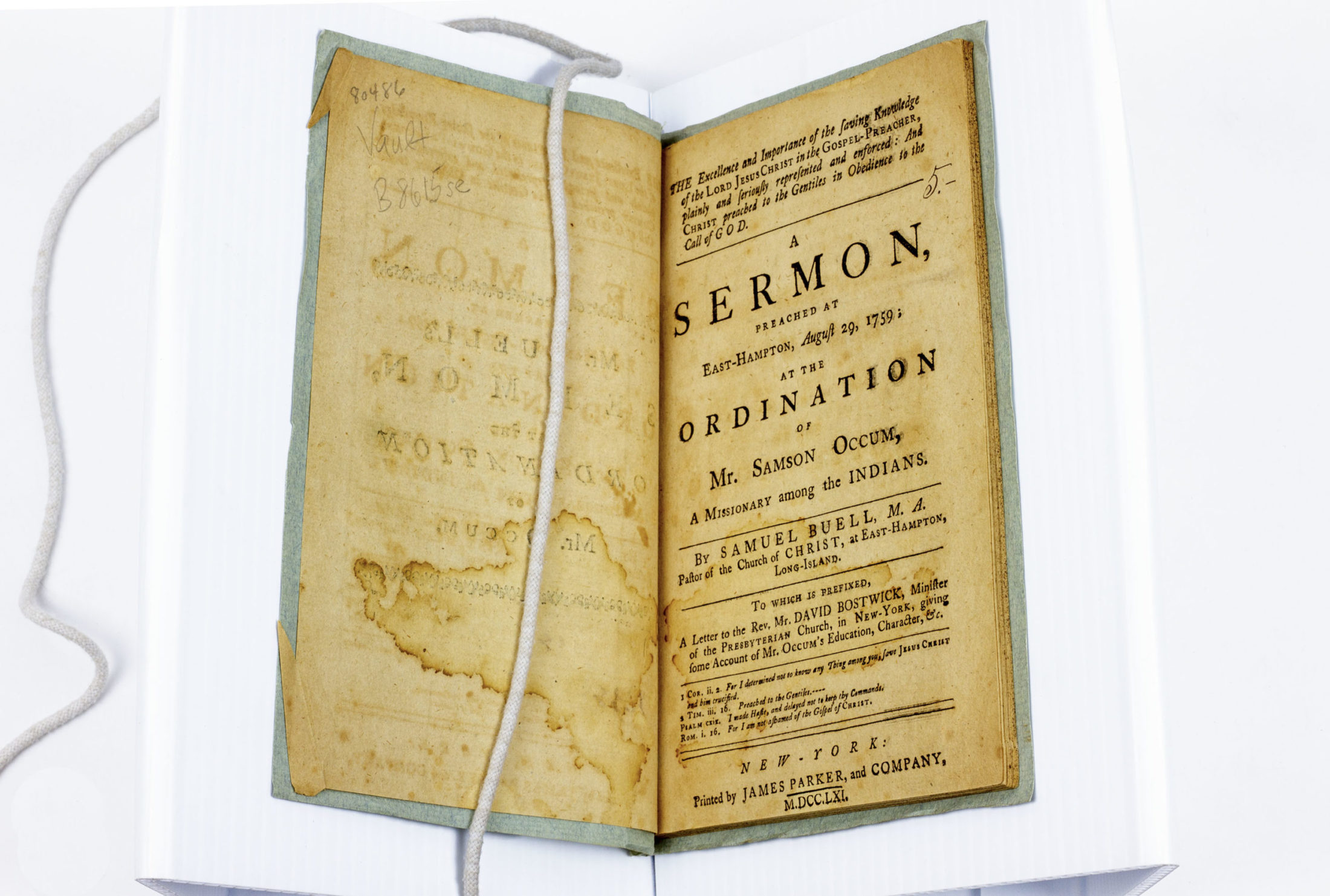

In 1749, Occum began the first of his ministries among American Indian tribes, which over the next few decades would include Montaukett, Lenape, Oneida, and Iroquois peoples. Wheelock arranged for groups like the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge to pay Occum, but he received far less than a white itinerant preacher would have. This injustice influenced Buell to recommend Occum’s ordination into the Long Island Presbytery in 1759, a position that provided Occum with a more stable source of financial support.

A Sermon preached at East-Hampton…at the Ordination of Mr. Samson Occum, 1761

BX7233.B7982 E8 1761

Brooklyn Historical Society

Unlike many of his American Indian contemporaries, Occum received a formal education that enabled him to leave an extensive written record of his life. Occum did not see converting as embracing “civilization” but rather as utilizing a platform through which he could achieve some measure of equity with his white neighbors. Embracing Christianity connected Occum to powerful men like Buell, with whom Occum could attempt to negotiate on behalf of his people.

Years of mistreatment fueled Occum’s disillusionment with the religious establishment, which through its actions reasserted time and again that Occum would never truly be their equal because of his race. In the 1770s, Occum organized a Pan-Indian settlement called Brothertown in upstate New York, where he and many of Long Island’s surviving American Indians immigrated. Occum’s faith allowed him to transform his community, but perhaps not in the way his white mentors had envisioned.