When George Washington Came to Long Island

The Mystery of a Portrait Miniature

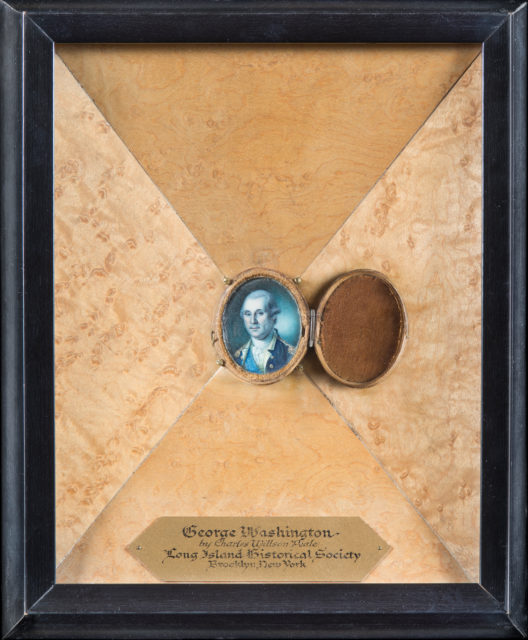

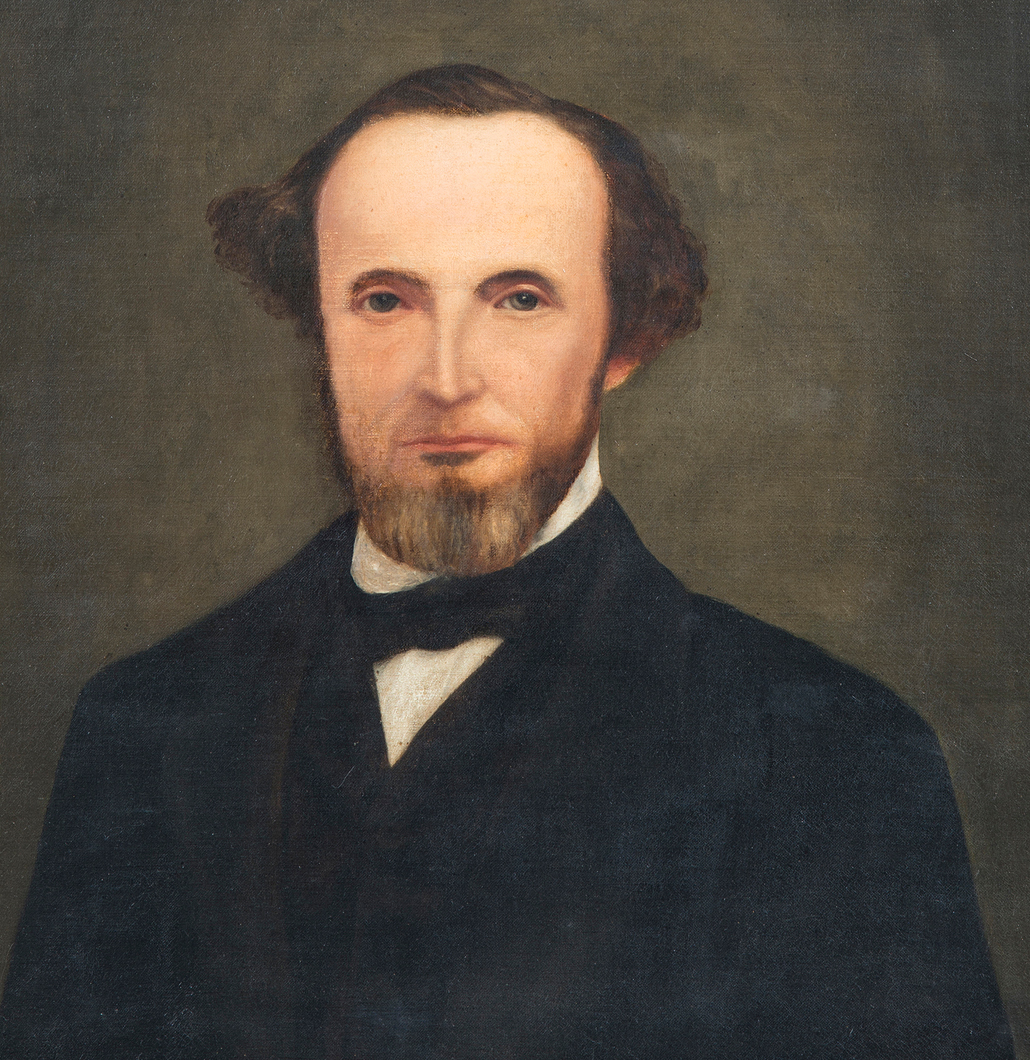

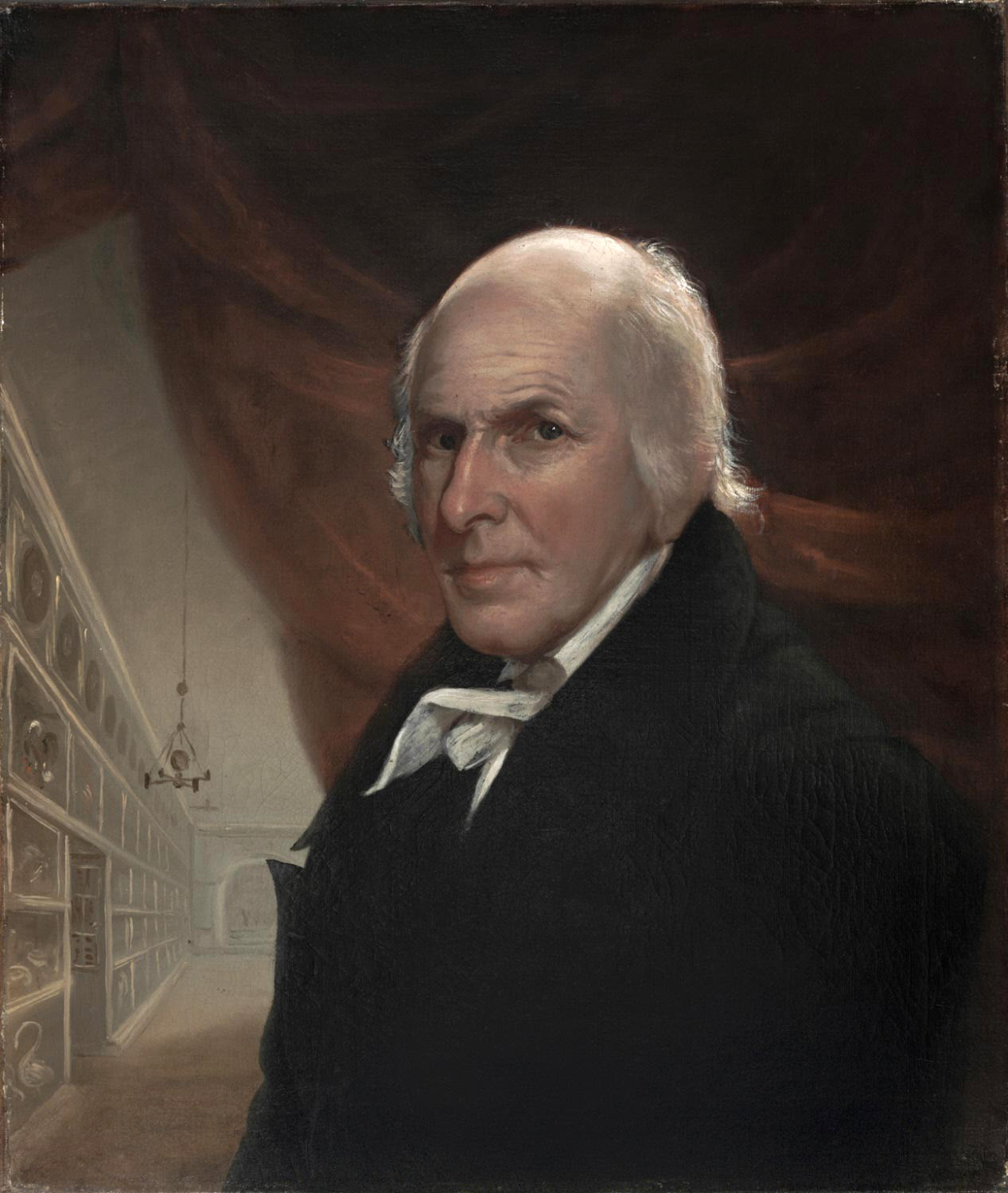

This two-inch portrait miniature of George Washington is one of the smallest and most significant decorative art items in the BHS collection. Washington is depicted as a military leader, the blue coat and cream waistcoat of his Continental Army uniform topped with the blue silk sash that denoted his status as commander-in-chief. Family legend has it that this miniature was painted by Charles Willson Peale, a prolific portraitist, naturalist, scientist, museum proprietor, and fellow soldier. The soft curves and highlights of Washington’s face, typical of Peale’s style, support this claim.

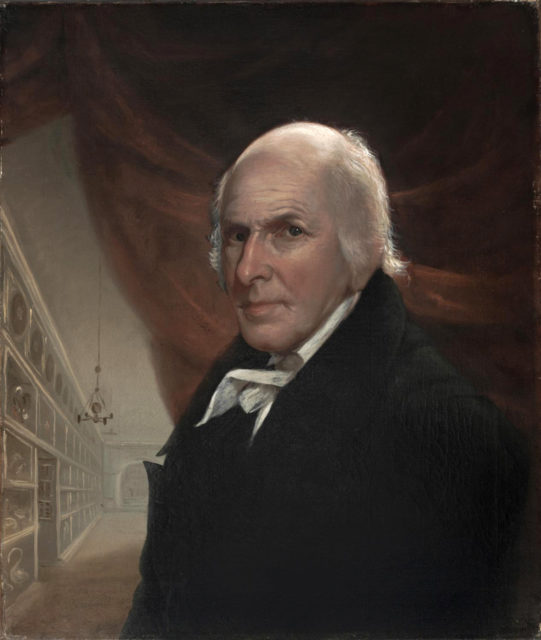

Self-portrait in the Museum, 1822

Charles Willson Peale

2015-1-1

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Between 1772 and 1795, Washington sat down with Peale for no fewer than seven portraits. In 1779, Peale completed a full-length portrait of Washington that celebrated his January 1779 victory at the Battle of Princeton. Even before the painting’s completion, Peale was inundated with requests for copies. The painting also became the source for portrait miniatures of Washington like the one in the BHS collection.

George Washington at Princeton, 1779

Charles Willson Peale

1943.16.2

Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

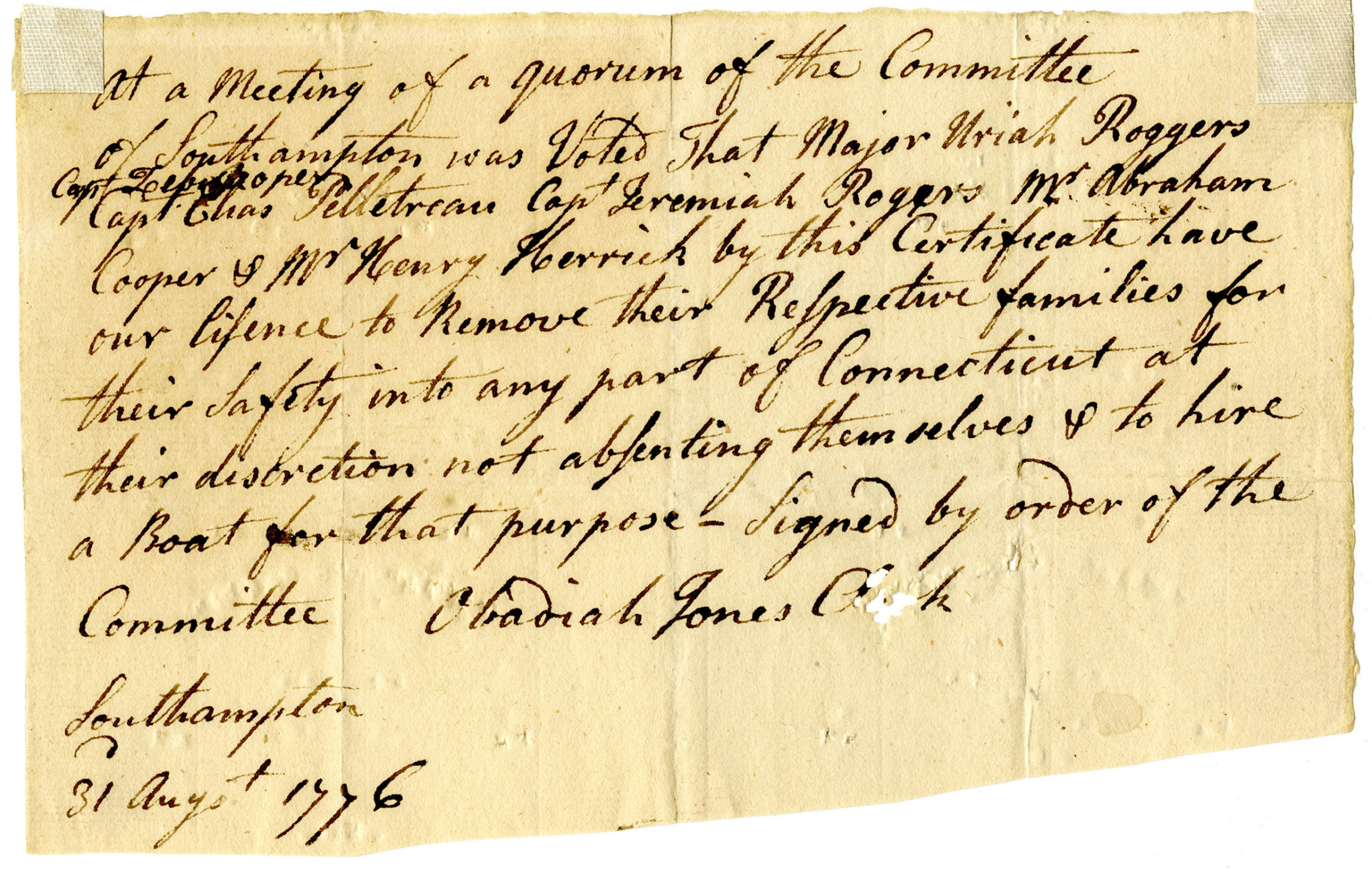

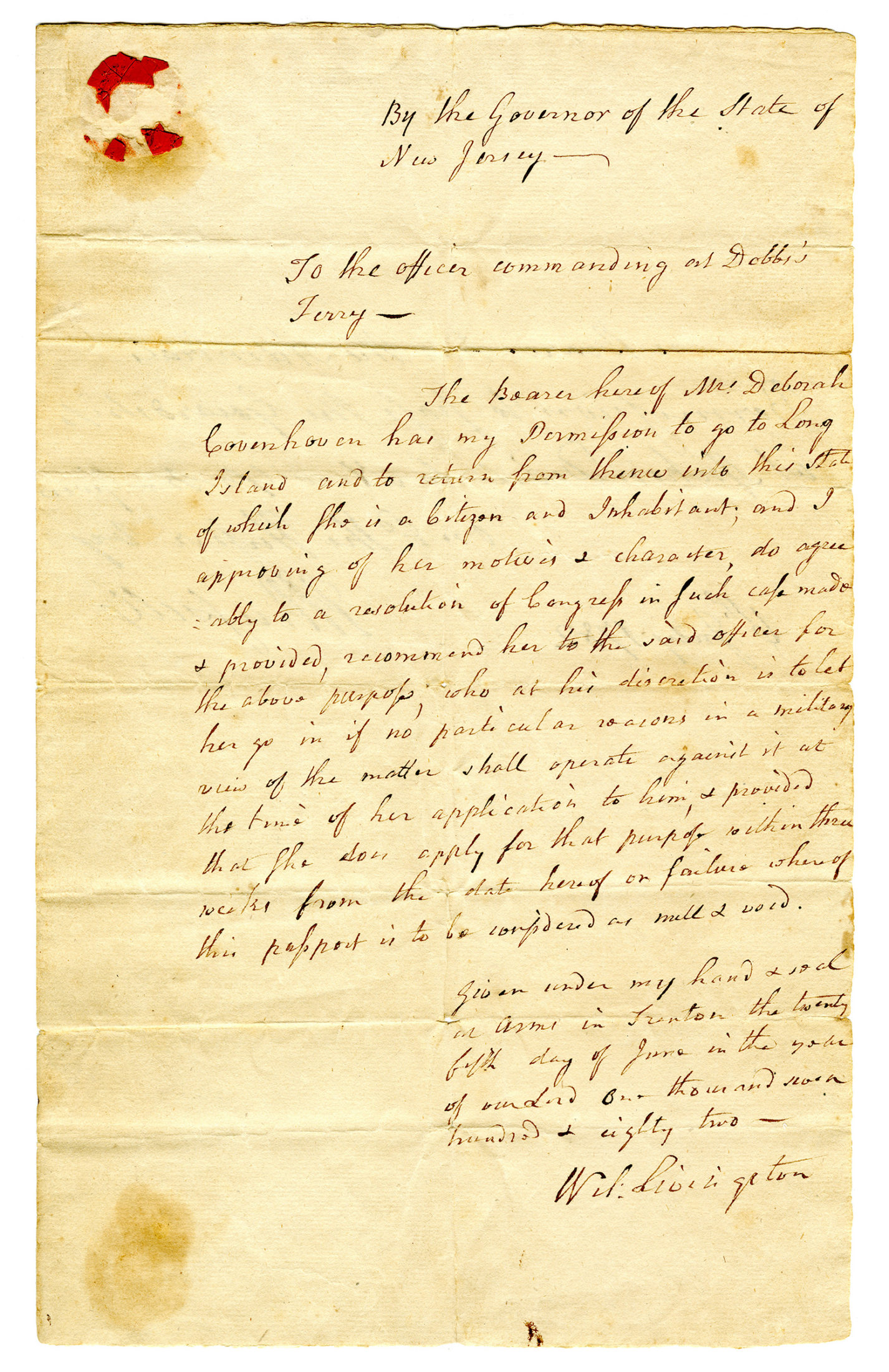

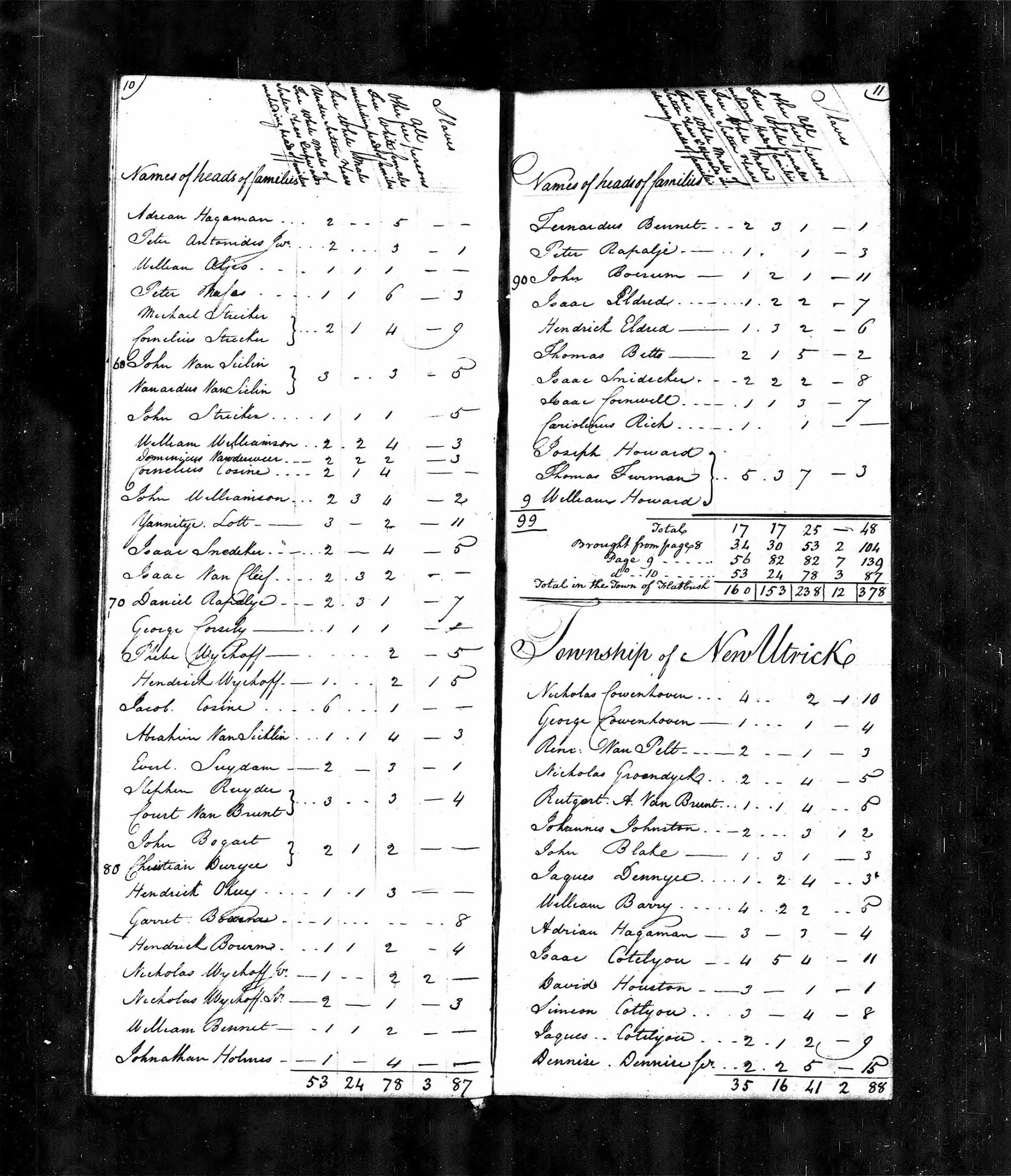

This portrait miniature was given to the Long Island Historical Society (today the Brooklyn Historical Society) in 1883 by Brooklynite Robert Benson (1812–1883). According to Benson, the original local owner was his maternal great-grandfather, Nicholas Couwenhoven from the village of New Utrecht, today the southern section of Brooklyn across the Narrows from Staten Island.

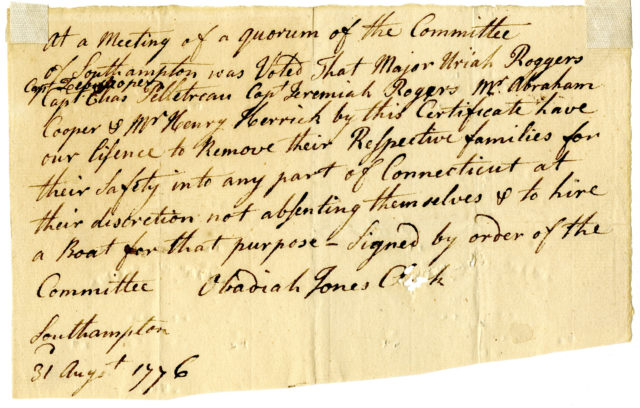

Following the Revolutionary War, Washington became a patriotic symbol for the new nation and it was common for Americans to display portraits of their first president in their homes. Newly discovered information about Couwenhoven and his journey through the Revolutionary War makes his ownership of this portrait miniature an intriguing mystery.