Negotiating Captivity and Freedom

The Different Fates of American Prisoners of War

Couwenhoven family legend claims that Nicholas received this portrait miniature from Colonel Nathaniel Ramsay, a Continental Army lieutenant colonel from Maryland and brother-in-law of the miniature’s creator, Charles Willson Peale. How Couwenhoven and Ramsay became acquainted and the role their relationship, represented by the exchange of this miniature, played in Couwenhoven’s postwar legal battles reveal the little-known history of American prisoners of war during the Revolution.

On June 28, 1778, Ramsay was wounded and captured by the British at the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey. Like most American prisoners, Ramsay served out his sentence in New York City. Although estimates vary, between 1776 and 1783 as many as 30,000 American soldiers may have been held prisoner throughout the city. Ramsay was lucky. As a high-value officer-captive, he was held in a private home on western Long Island in Flatbush. His captivity was spent in much better conditions than American foot soldiers confined in overcrowded makeshift cells or British prisoner ships like the HMS Jersey, docked in Brooklyn’s Wallabout Bay. As many as 18,000 Americans died while imprisoned, more Americans than perished on the battlefield.

Prisoner Ship Jersey, late 19th century

Edwin Stafford Doolittle

M1974.46.1

Brooklyn Historical Society

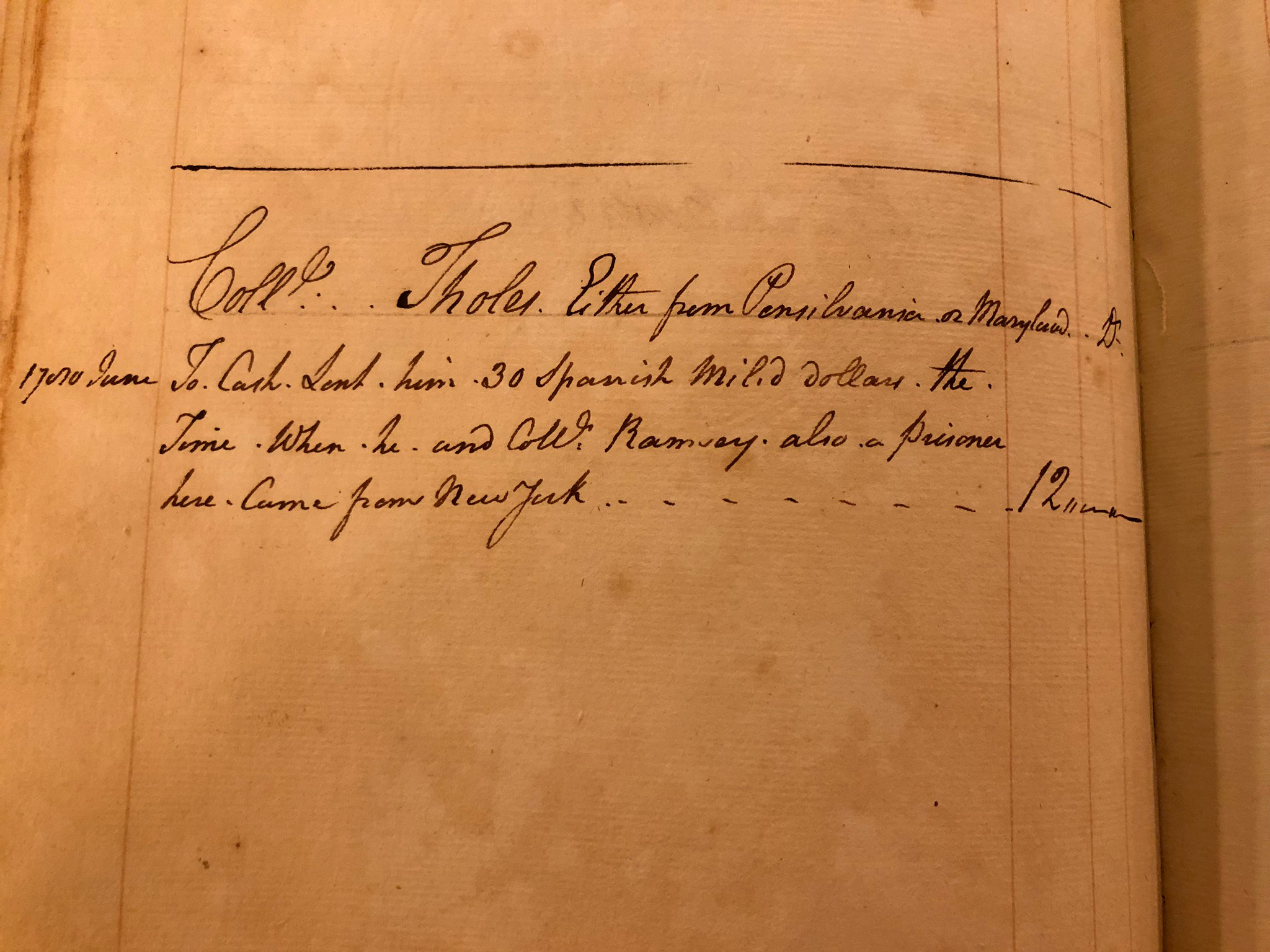

Ramsay’s release took two years to negotiate. During that time, he got to know the locals, including Couwenhoven, who had taken a great interest in American prisoners. Couwenhoven’s wartime account book (in the BHS collection) documents hundreds of dollars of his own money loaned to American prisoners to pay their wartime expenses, including lodging and clothing.

In June 1780, Couwenhoven lent “30 Spanish milled dollars,” or silver coins, to Ramsay and a fellow officer-prisoner, Colonel Oliver Towles, to fund the cost of their travel into Manhattan for a meeting with the British that ultimately ensured their release. While speculative, the role Couwenhoven played in this meeting may have been the reason that Ramsay gifted the miniature of Washington to him.

Revolutionary War Era Account Book, 1780

Nicholas Covenhoven papers (ARC .283)

Brooklyn Historical Society

Nineteenth-century Brooklyn historian Henry Stiles wrote that Couwenhoven’s efforts on behalf of American POWs were “merely a polite concession to the rising fortunes of America,” and indeed, they may have been. In 1783, New York State authorities summoned Couwenhoven to stand trial as a suspected loyalist. For suspected traitors on trial, testimonials and support from family and friends were critical to prove their innocence. Couwenhoven’s most important defense likely came from George Washington himself, who wrote in a letter that he had “frequently heard from the American officers who have been prisoners on Long Island that on all occasions you [were] their friend.” Couwenhoven was cleared of all charges, thanks in no small part to prisoners of war like Ramsay; Ramsay’s brother-in-law Charles Willson Peale; and, of course, Washington. This portrait miniature was most likely Couwenhoven’s ticket to freedom.