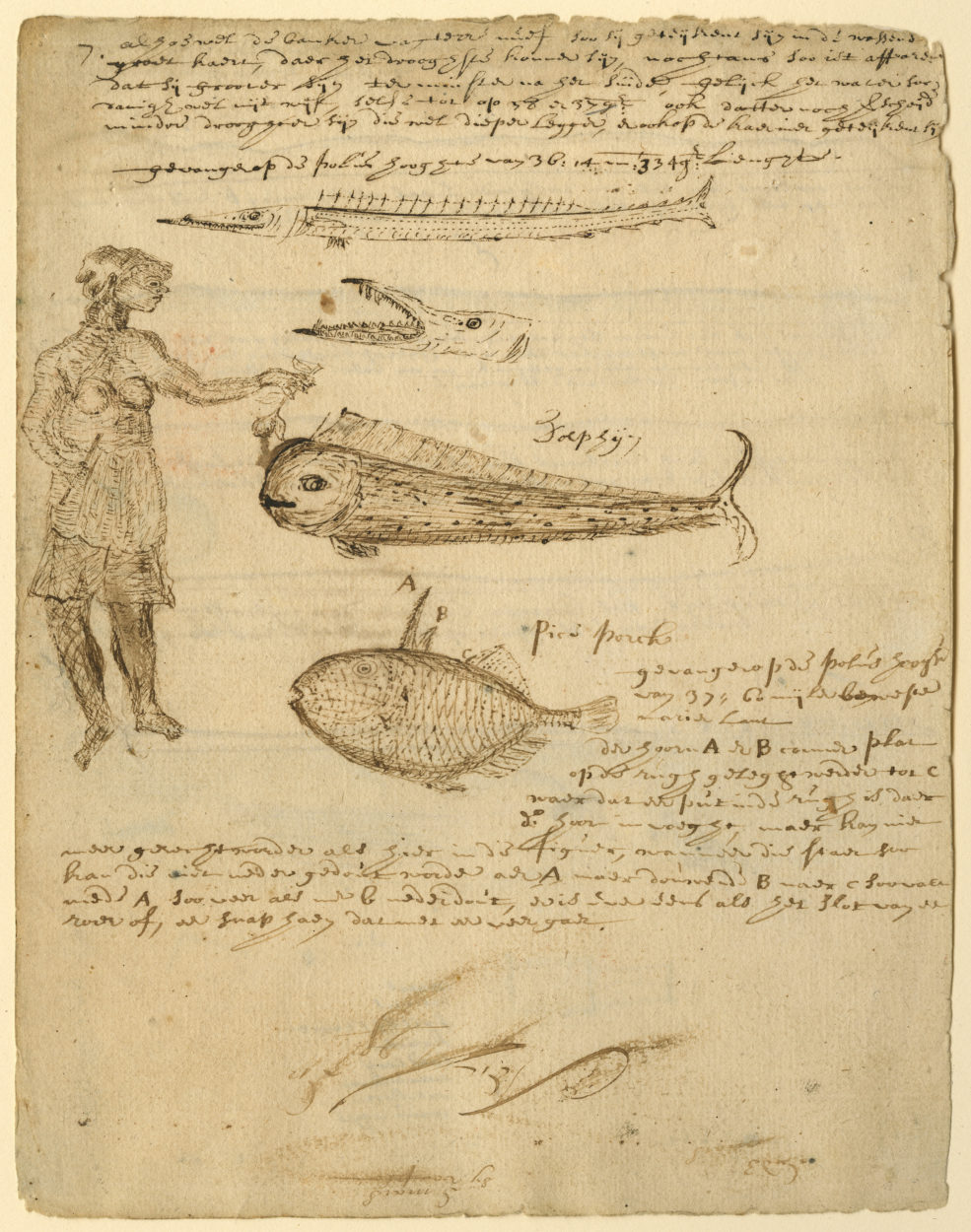

“Indians at the East End of the Isle”

Negotiations and the Special Commission on Indian Affairs

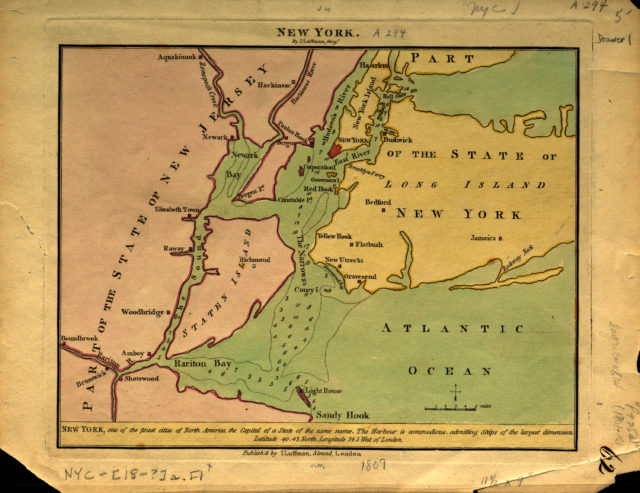

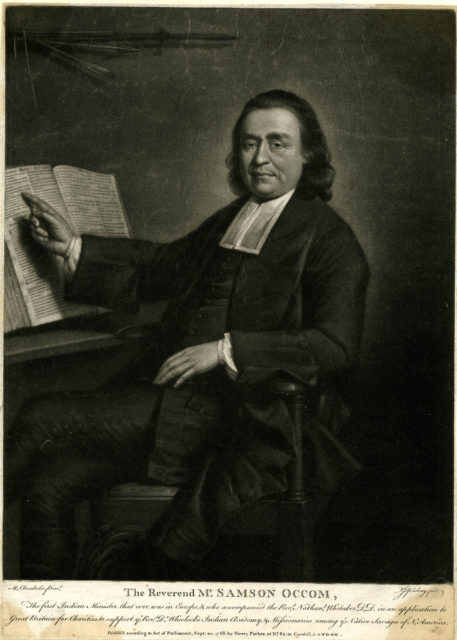

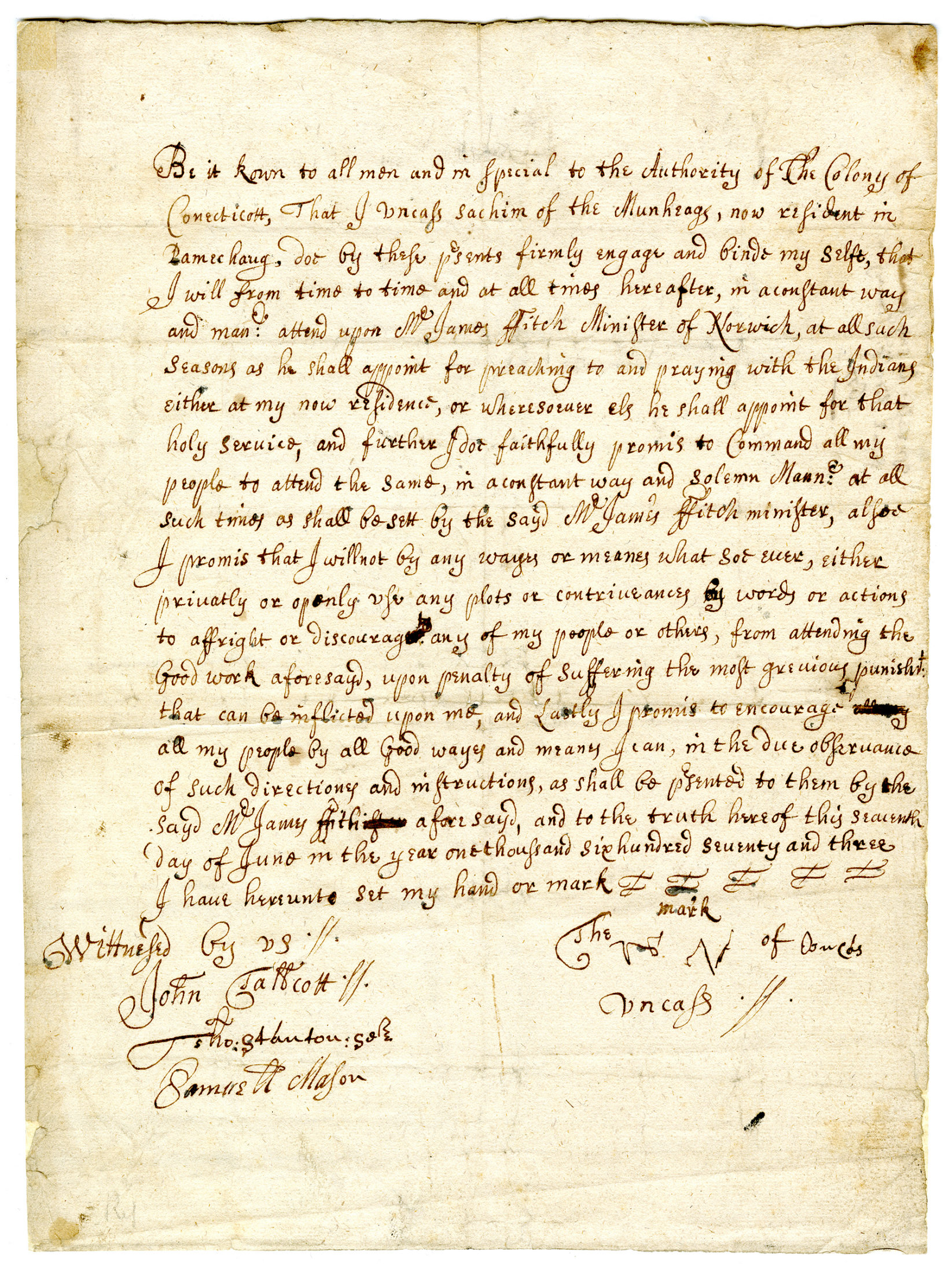

As a prominent Long Islander, William Wells served as an intermediary in numerous trials of transitions. In 1666, New York’s first English governor, Richard Nicolls, requested Wells establish and oversee a “Special Commission on Indian Affairs.” The commission was responsible for hearing and resolving land disputes between the English and American Indians on the East End. The establishment of the commission reveals the continuing conflict between Europeans and local American Indian groups and the attempts of Long Island’s new English government to diffuse tensions in the region.

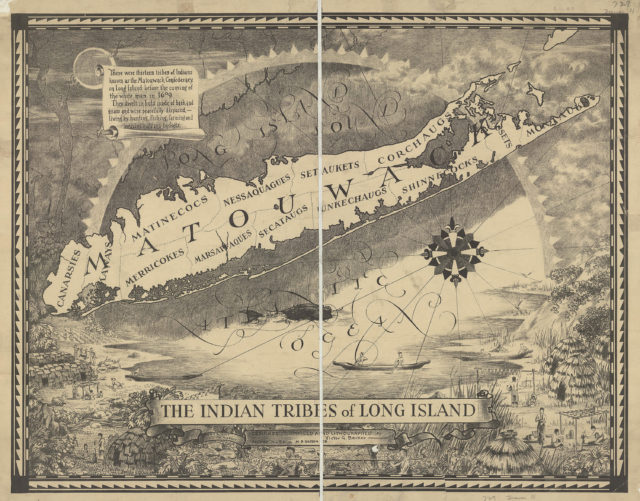

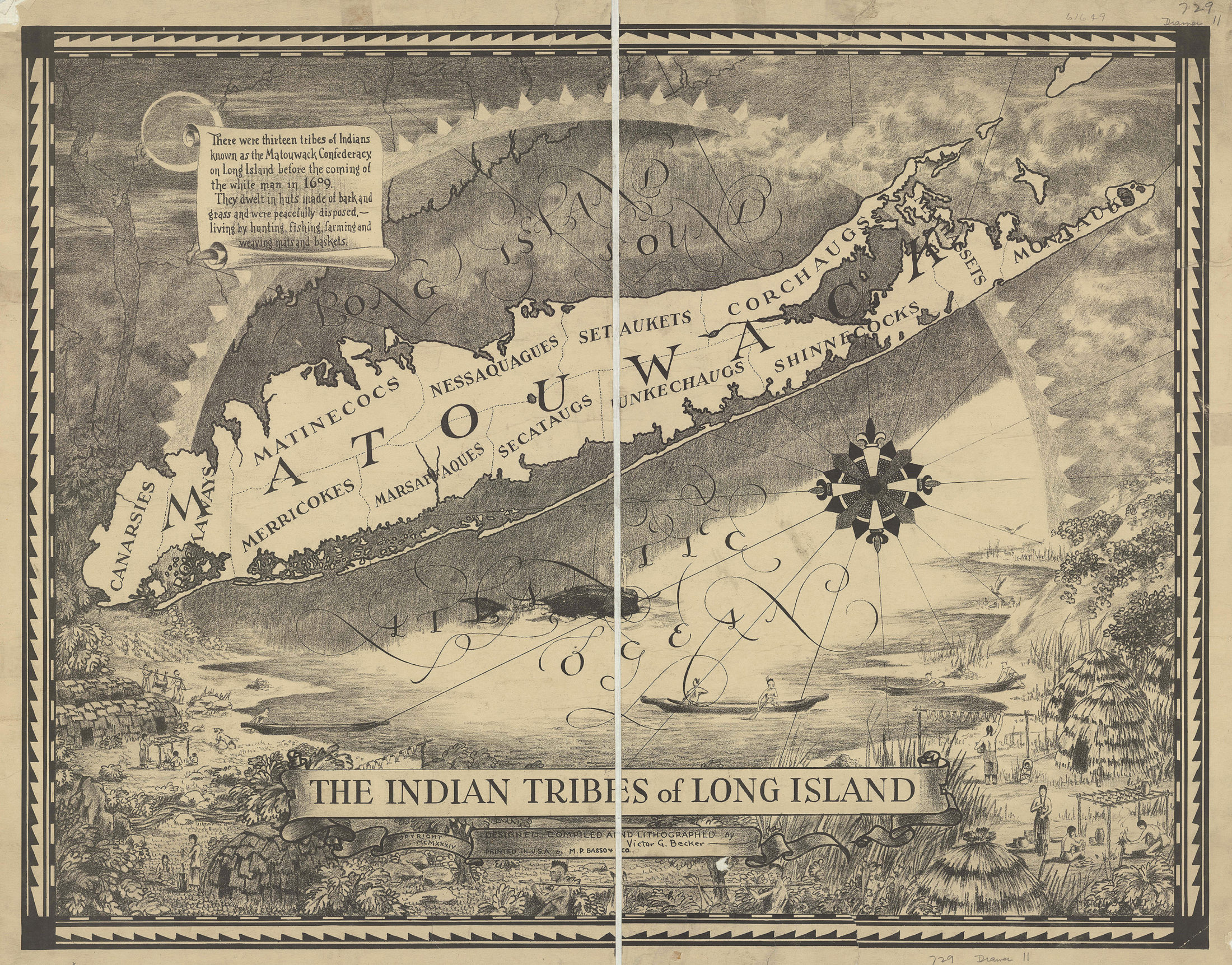

The Indian tribes of Long Island, circa 1934

Designed, compiled and lithographed by Victor G. Becker

L.I.-193.Fl

Brooklyn Historical Society

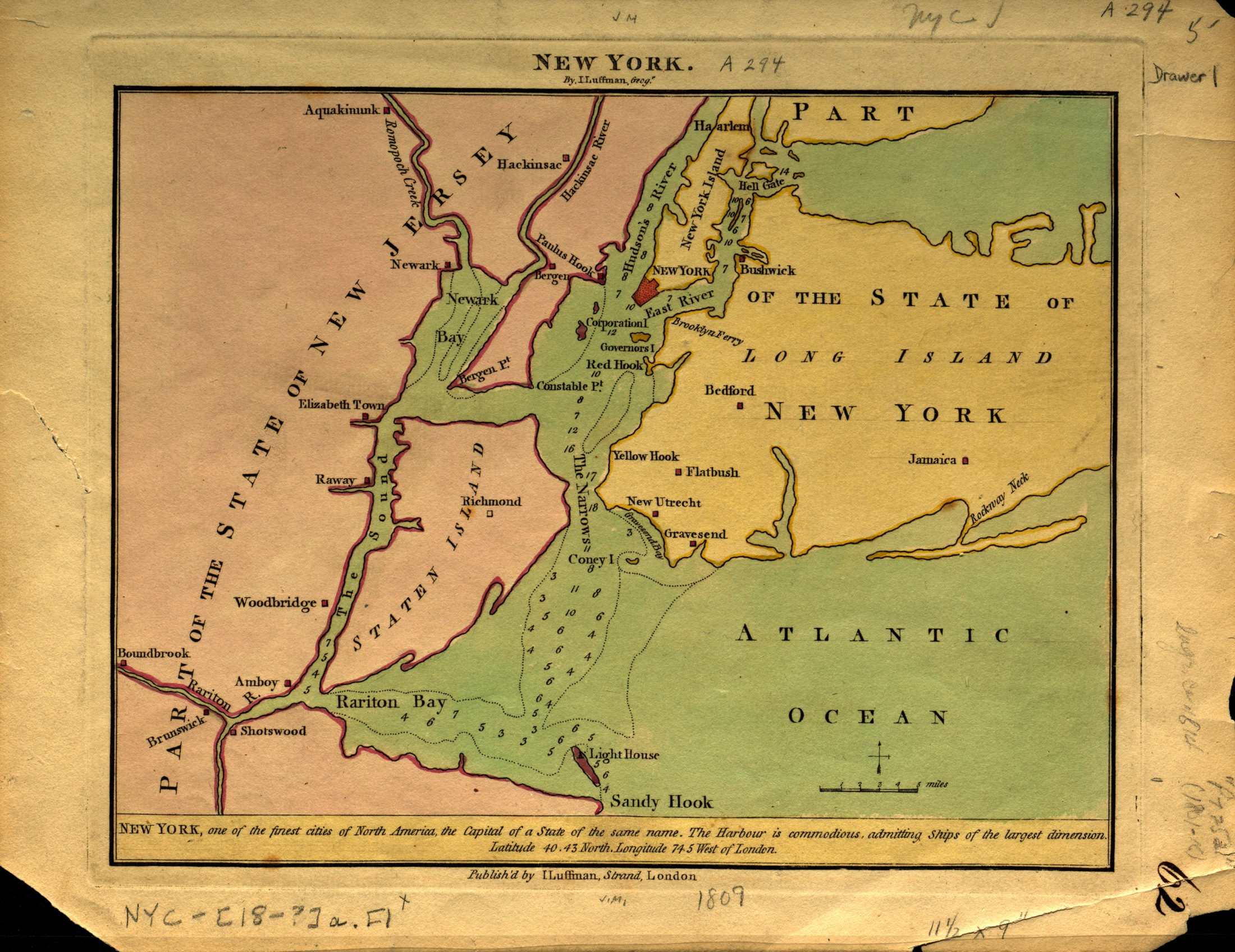

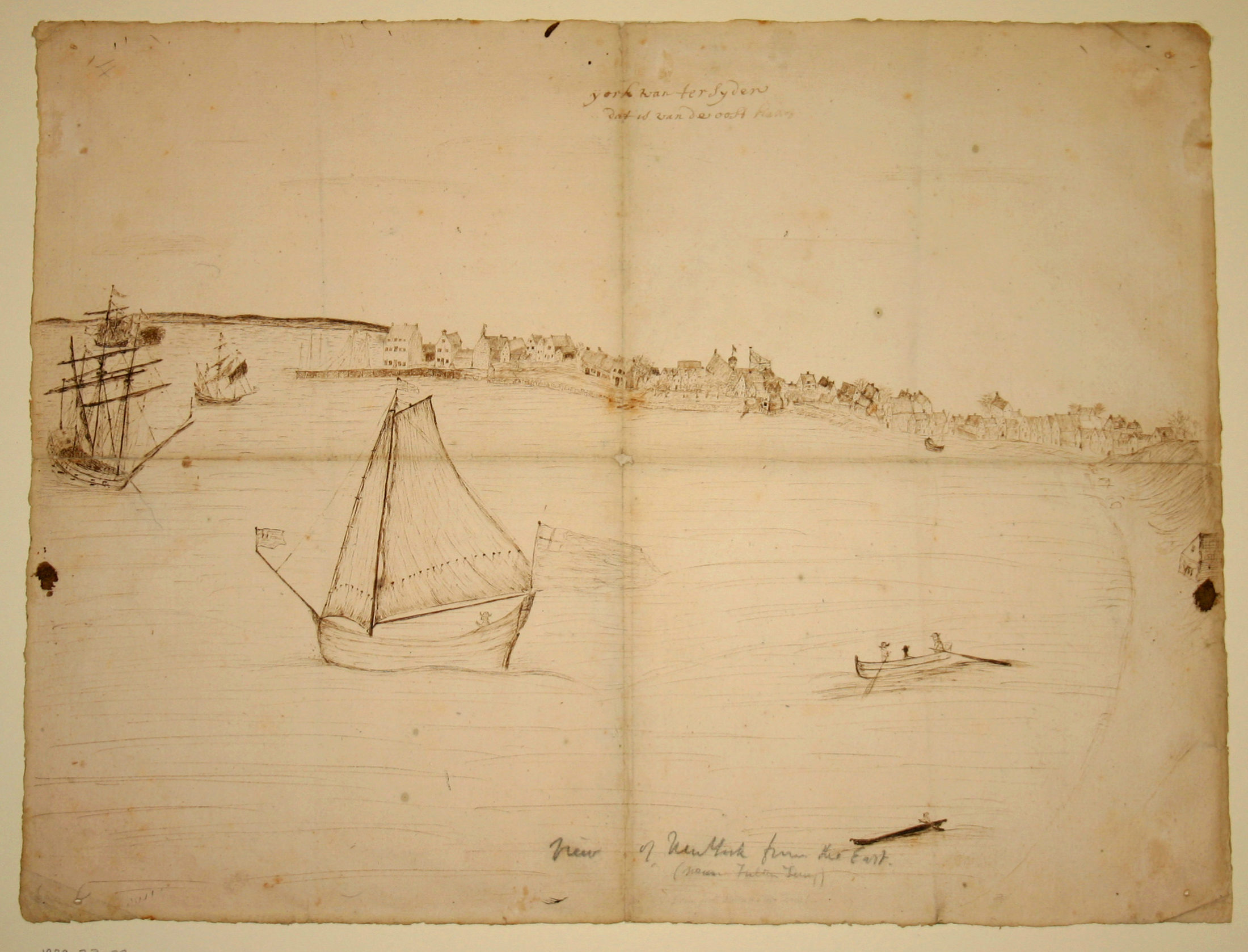

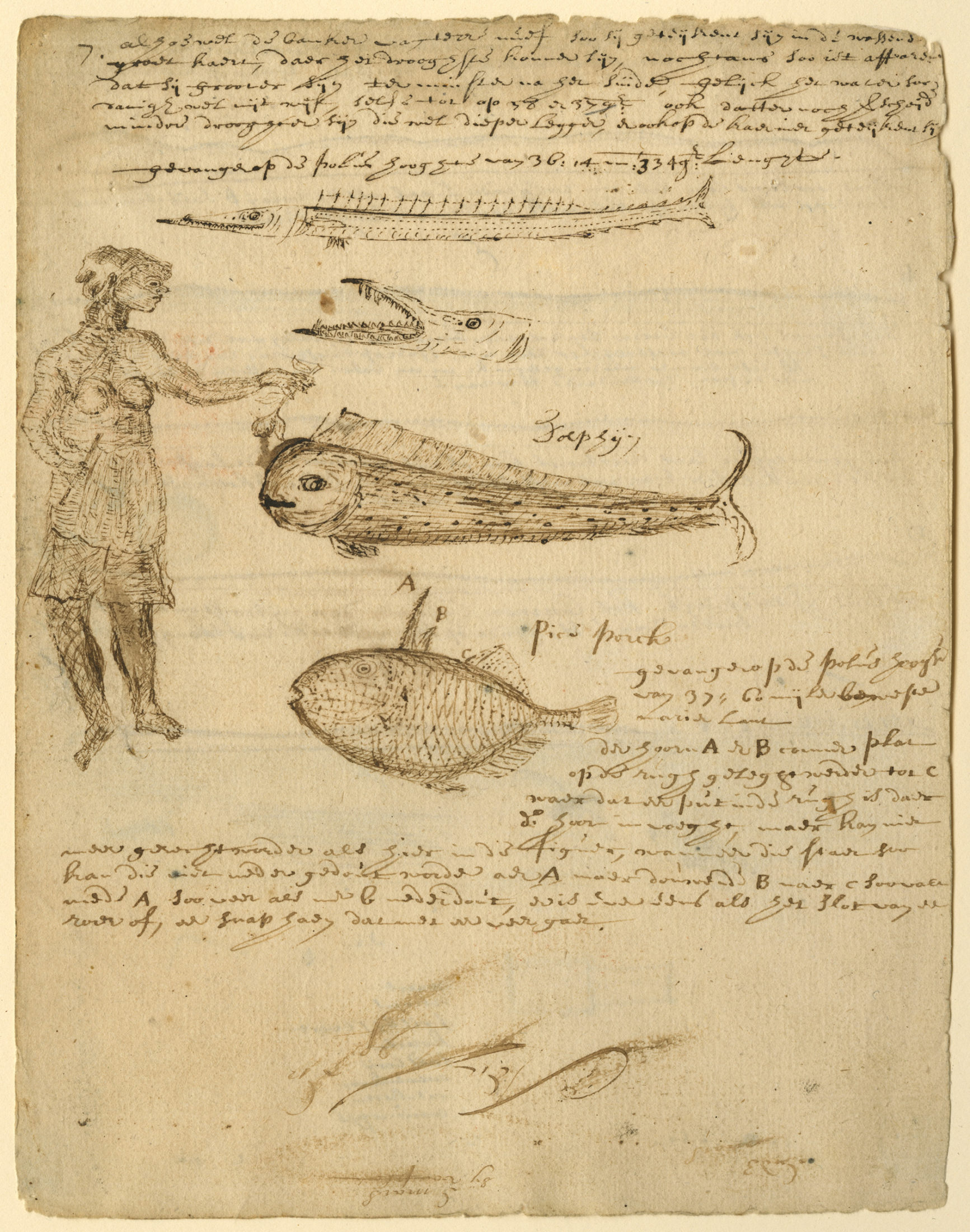

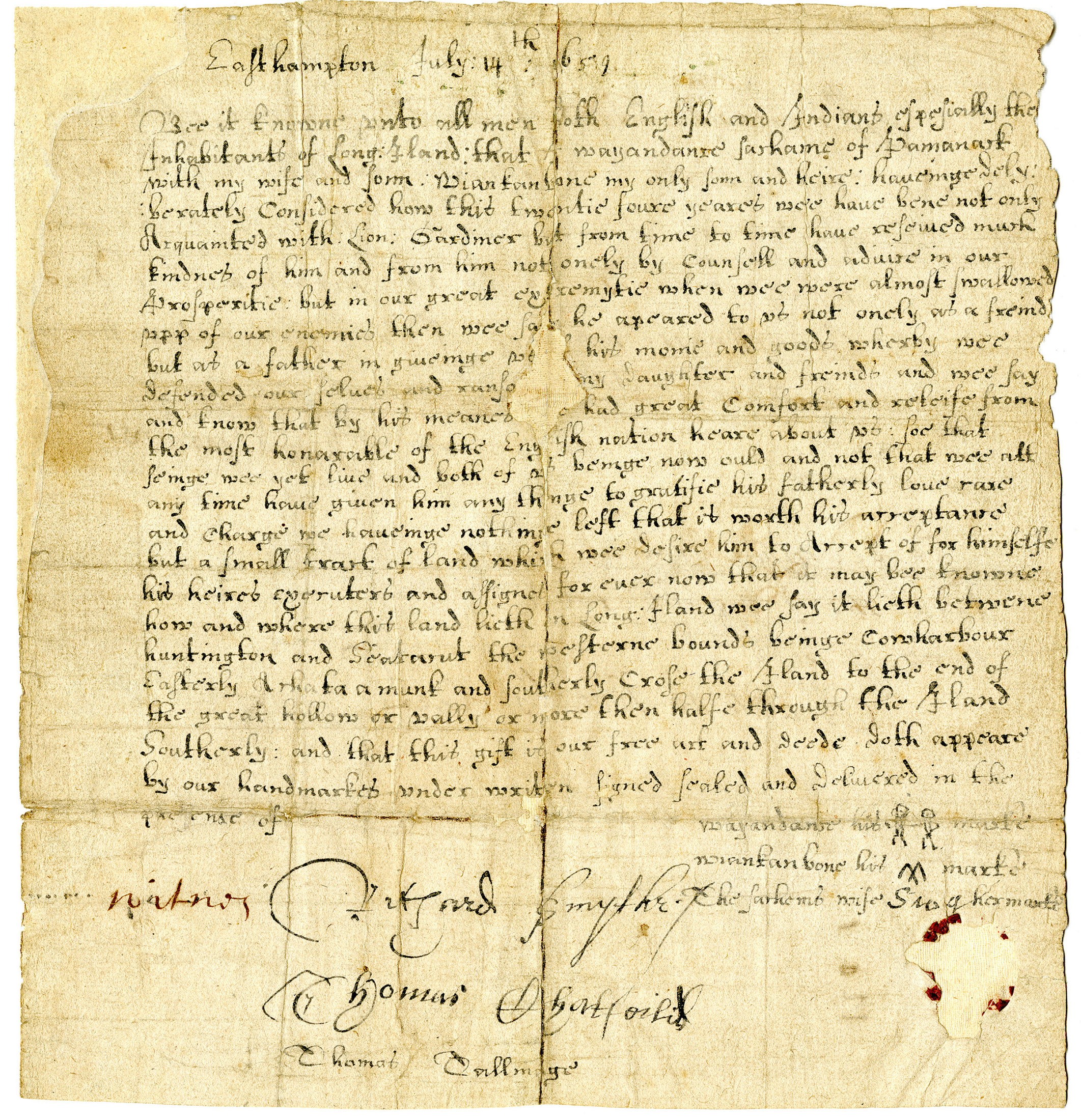

The arrival of Englishmen on Long Island in the mid-1600s kicked off decades of diplomatic negotiations between them and local indigenous communities like the Montaukett on Long Island’s South Fork. Negotiated exchanges of land and goods opened the door to European settlement on Long Island and initially provided Native American communities with the protection of a powerful ally. As the first century of contact drew to a close, though, disagreements and misunderstandings arose more frequently, requiring government intervention.

Land deed for property near Smithtown between Wyandanch and Lion Gardiner, 1659

Smith families papers (ARC .244)

Brooklyn Historical Society

From 1666 to 1674, Well’s Special Commission on Indian Affairs heard testimony and issued decisions on disputes between “Christians and Indians” largely relating to land sales, border disputes, and accusations of trespassing and property damage. The Duke’s Laws, the legal system established in 1665 by Governor Nicolls and his council (including Wells), included nine ordinances relating specifically to Indians, intended to help mediate conflicts before they turned violent. American Indians were understandably reluctant to solve problems within this foreign system, one which undoubtedly skewed heavily in favor of the English.

Mention of the special commission disappears from colonial records in the mid-1670s, when it was likely absorbed into the larger colonial court system. As the 1600s drew to a close, Long Island’s American Indian population shrank dramatically, decimated by outbreaks of diseases. Those who survived saw their rights curtailed and ancestral lands shrink and, by the late 1800s, real estate developers eager to turn Long Island’s East End into a suburban retreat for New York’s wealthy.

Guide map of Wompenanit, Hither Hills, and Hither Woods,

belonging to Frank Sherman Benson and Mary Benson at Montauk, L.I., 1905

L.I.-1905a.Fd.RA

Brooklyn Historical Society