Was America’s “Freedom of Religion” Born in New Amsterdam?

Anthony Van Salee, Religious Dissenters, and Long Island

Research into Anthony Van Salee’s New Amsterdam has contributed to the belief that the Dutch embraced cultural diversity and religious tolerance and can be credited with laying the groundwork for the United States’ later constitutional freedom of religion. However, the lived experiences of individuals like Van Salee and other “religious dissenters” tell a different story.

The Dutch Republic did not endorse religious coercion, but the Reformed Dutch Church was the official, state-sponsored religion in New Amsterdam. When individuals of other faiths worshipped publicly, they inadvertently challenged the authority of the church and thus, the state. These challenges led state officials to persecute certain communities or banish them from Manhattan. Once removed, many dissenters like Van Salee put down roots in the colony’s Long Island frontier.

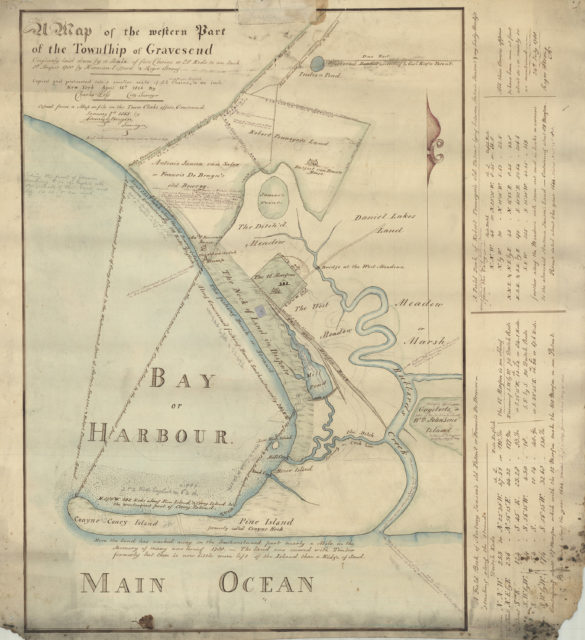

Map of the western part of the Township of Gravesend, 1800s

Teunis G. Bergen

Bergen-[18–?]uu.Fl

Brooklyn Historical Society

In 1645, just two years after Governor Willem Kieft signed Van Salee’s land deed, Van Salee had new neighbors: English noblewoman Lady Deborah Moody and her followers. Moody was an Anabaptist, a member of a radical Protestant sect that believed, among other things, that baptism should only be bestowed upon consenting adults, not children. Those beliefs led to Moody being forced to flee England in 1639, and, in 1643, being forced to abandon the the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Following her expulsion from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Moody traveled to New Amsterdam, where Kieft contingently welcomed her. He allowed her to settle in the colony, on 7,000 acres of land on the frontier, on the southwestern tip of Long Island. There, Moody established the settlement of Gravesend, the only one of the six original European settlements on western Long Island not founded by Dutch settlers. Gravesend was also the first American settlement to legislate religious freedom in its founding charter.

Friends Meeting House, Westbury, 1878

Elias Lewis Jr.

V1972.1290a

Brooklyn Historical Society

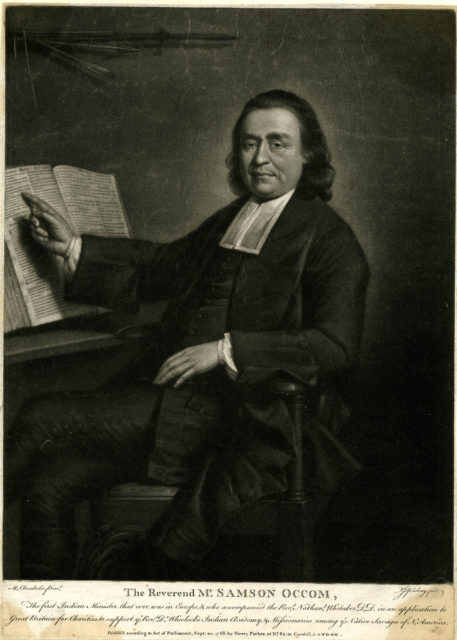

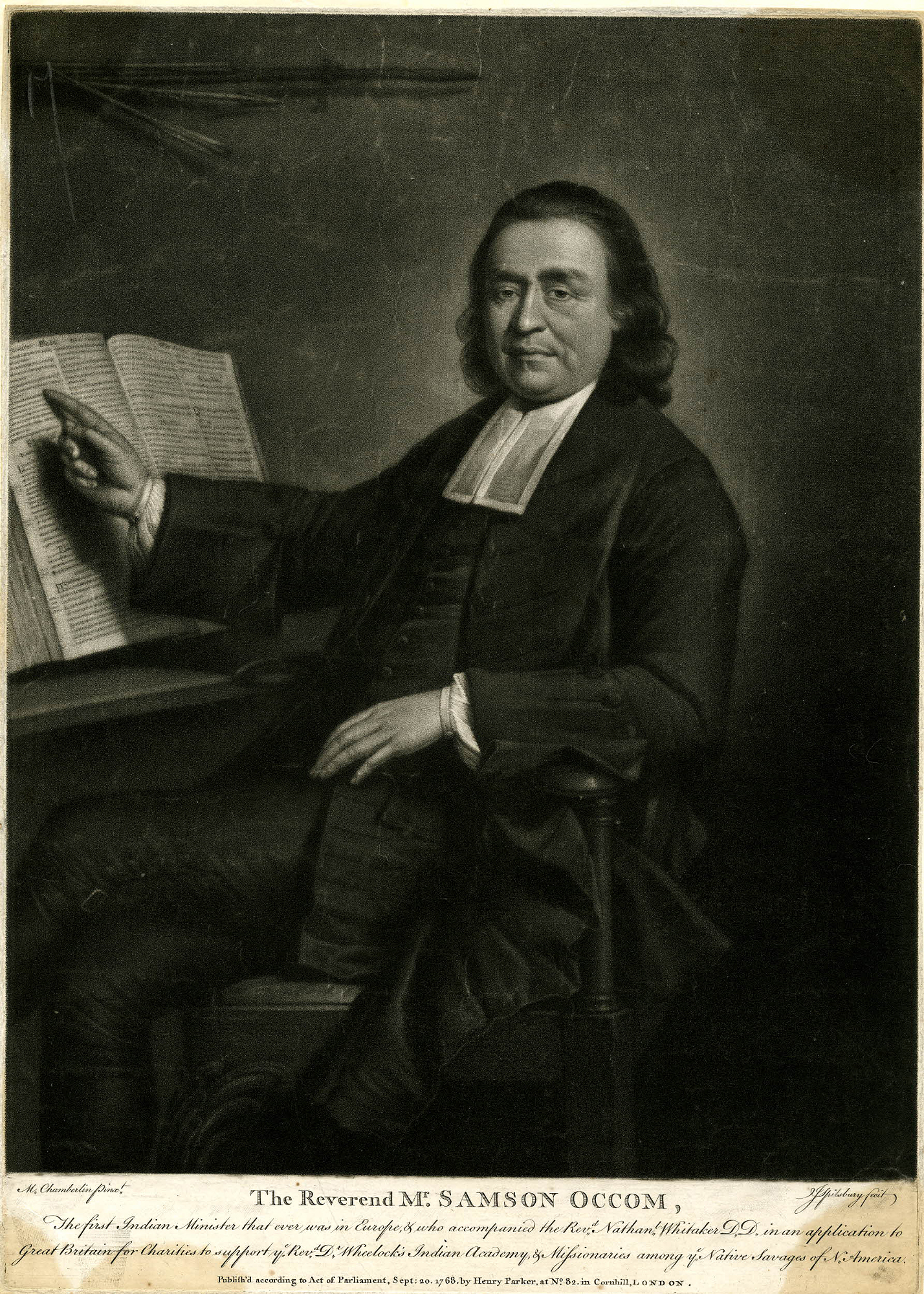

Moody likely opened Long Island to another controversial religious group, the Friends of God, more commonly known as the Quakers. Rejecting all sacraments, liturgies, and paid intermediaries like priests, the Quakers believed that all of the faithful were spiritual equals before God. Dutch Governor Peter Stuyvesant used their public proselytizing to banish the first group of itinerant Quaker preachers from Manhattan when they arrived in 1658.

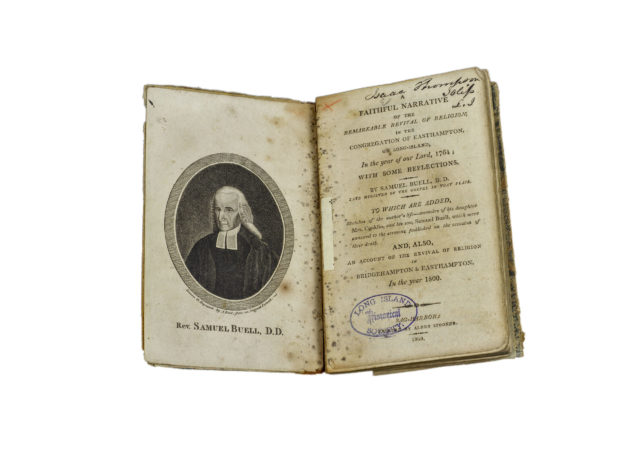

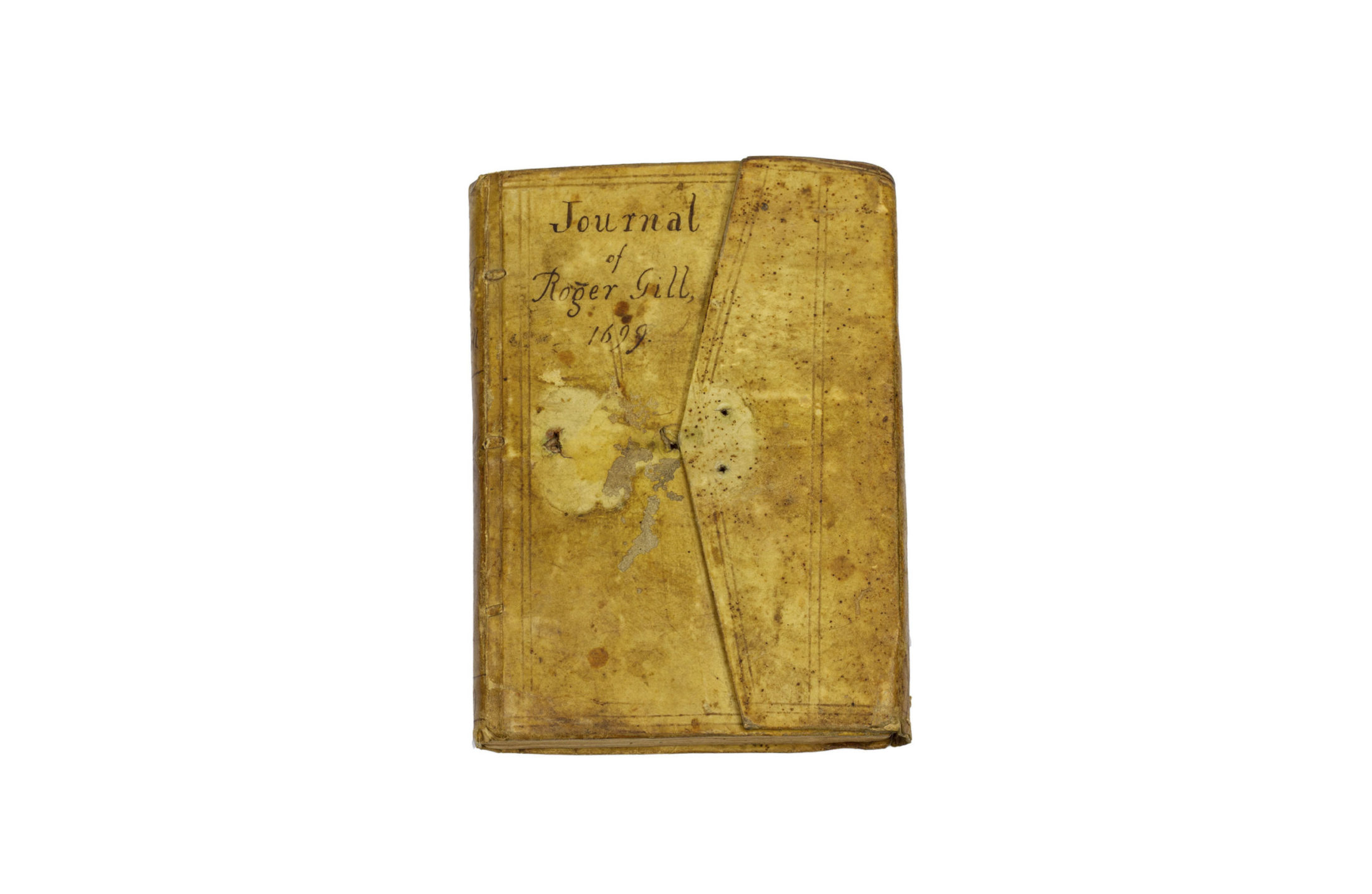

Journal of Roger Gill, 1698

1981.014

Brooklyn Historical Society

The Quakers crossed the East River, where they found an ally in Lady Moody and a foothold for their faith on Long Island. In the coming decades, the Quakers established Meetings in Gravesend, Jamaica, Oyster Bay, and Shelter Island, and gained followers. In the process of creating Quaker communities, they also attracted the ire of Governor Stuyvesant, who banned colonists from welcoming any Quakers into their homes. In 1657, the small Quaker community in Flushing, Queens, fed up with the Dutch government’s continued persecution, signed the Flushing Remonstrance, demanding the right to practice their religion freely.

Petitions like the Flushing Remonstrance should be seen as precursors to the United States’ constitutionally protected freedom of religion, not just the “tolerant” policies of New Amsterdam and other colonies.