Through a Pastor’s Eyes

Early Ecclesiastical History in the BHS Collection

Map of the southern part of the state of New York including Long Island, the Sound, the state of Connecticut, part of the state of New Jersey and islands adjacent, 1815

William Damerum (publisher)

E-US-1815.Folded

Brooklyn Historical Society

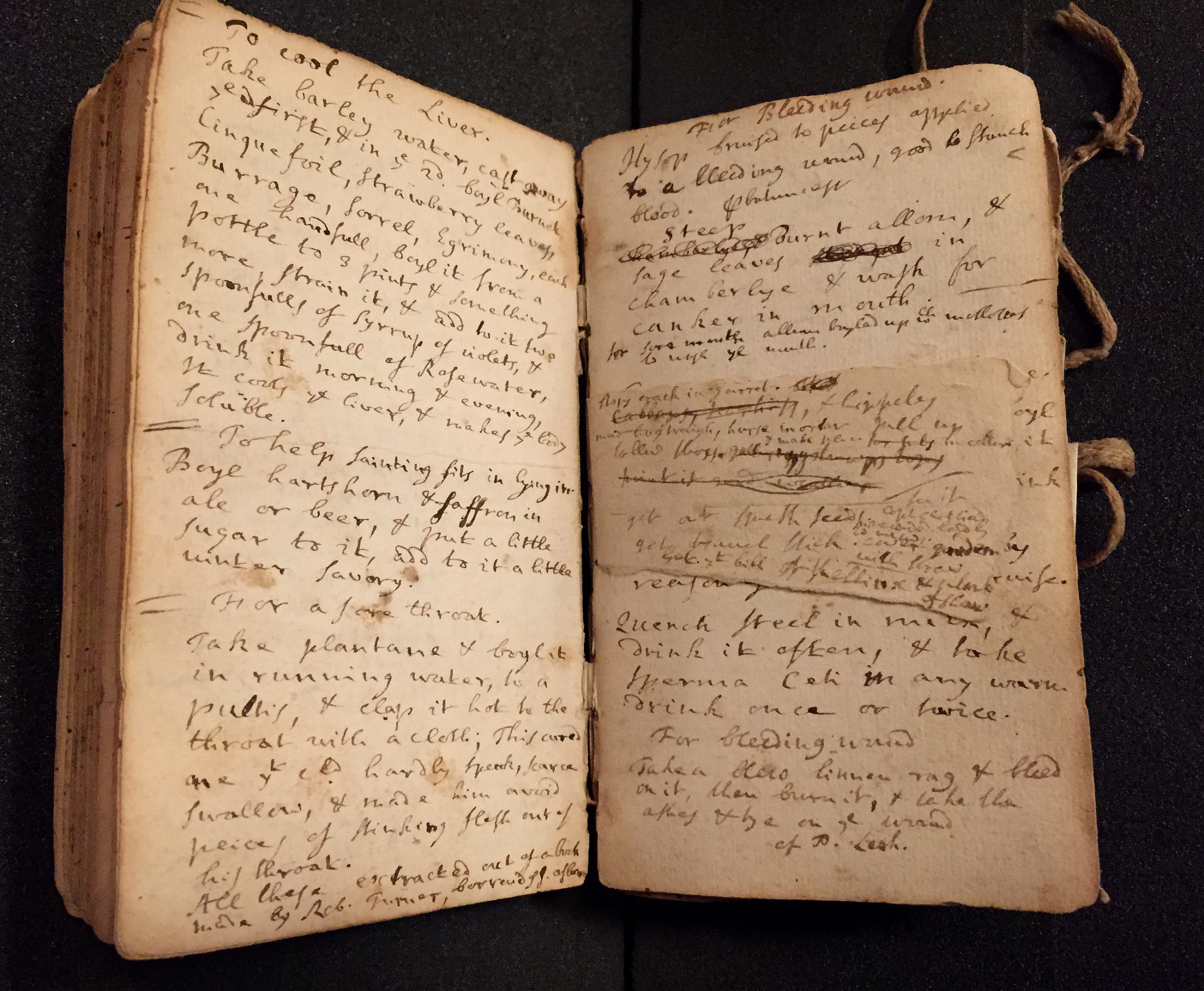

Two men guided the first century of religious life in East Hampton. The Reverend Thomas James presided over the local church from 1650 to 1699, followed by the Reverend Nathaniel Huntting from 1699 to 1746. During these formative years, negotiations and tensions with the neighboring Montaukett people were a frequent concern. James expressed interest in acting as a missionary among the local indigenous population; town records indicate most of his time was spent establishing the settlement and its local whaling economy. Indigenous peoples were an important source of information, including the potential uses of local plant life for food and medicine, for European settlers.

Nathaniel Huntting journal, 1697

Nathaniel and Jonathan Huntting papers (1974.075)

Brooklyn Historical Society

Rev. Samuel Buell dominated the second half of the 1700s, ministering from 1746 until his death in 1798. Buell’s tenure was marked by the religious revitalization and disruptions of the Great Awakening and the Revolutionary War. After the British victory at the Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776, many American rebels fled to safety across the Long Island Sound to Connecticut. Buell stayed in East Hampton and cooperated with occupying British forces. His steady correspondence with both British and American leaders helped him negotiate the trade of essential goods with Connecticut during the war. Neither a hardline patriot nor a loyalist, Buell explained to Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull that his primary concern during the war was “the Weal and Prosperity of my Native Country and the Public.”

Cordial Glass, 18th century

M1991.861.1

Brooklyn Historical Society

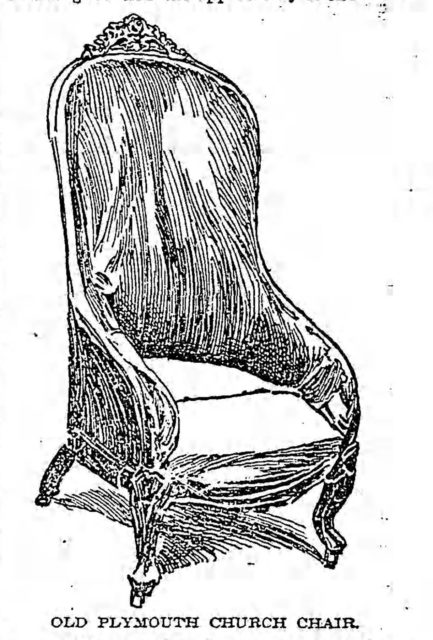

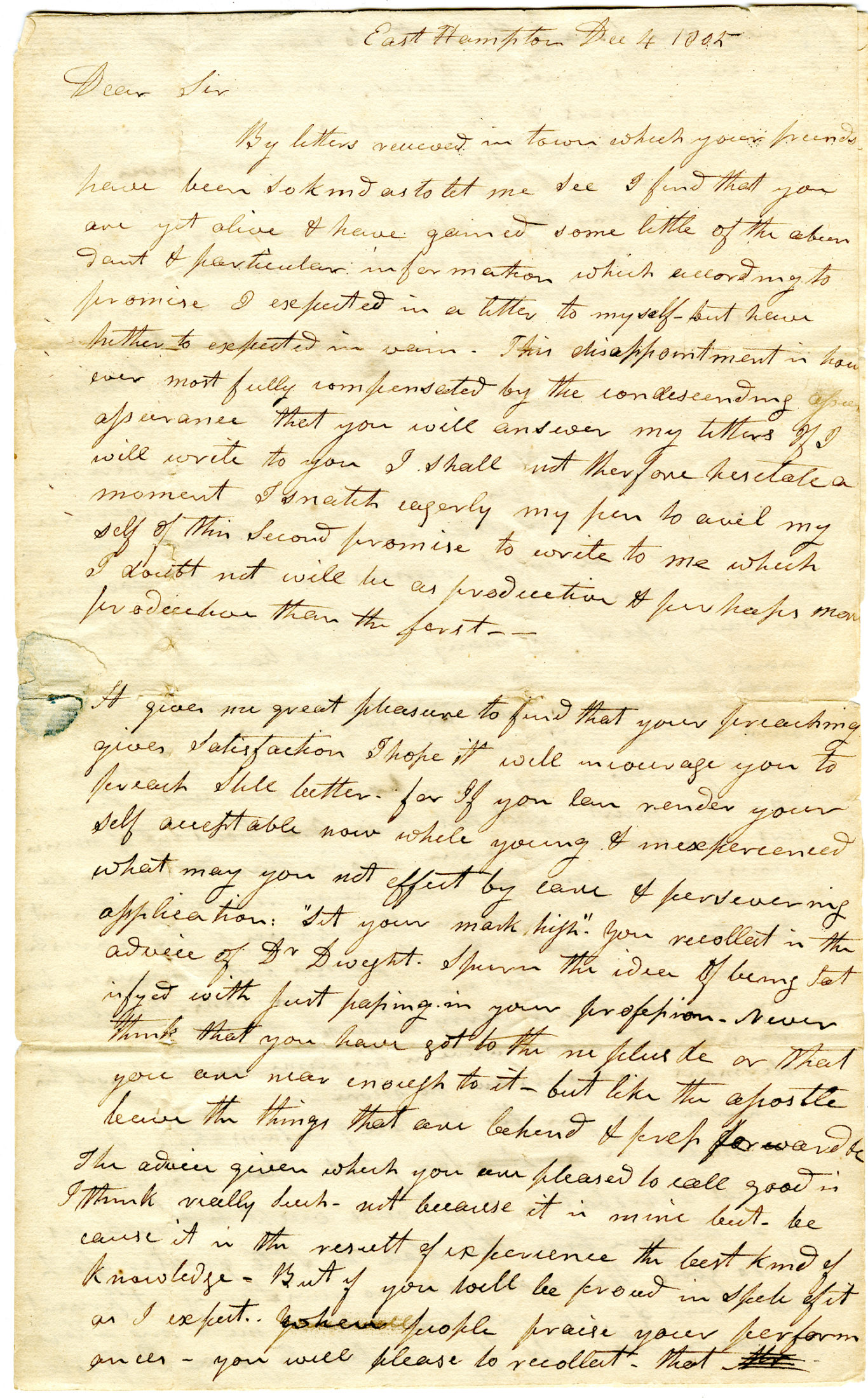

Buell’s successor, Lyman Beecher, spent the least amount of time on Long Island, but ironically he is the best-known public figure. Beecher arrived in East Hampton fresh from Yale College in 1799 and ministered there only until 1810. Known for his strict Presbyterian teachings, Beecher gained national notoriety for his activism and vocal positions in public debates about the era’s pressing moral issues, including temperance and abolition. Several of his children, among them Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Ward Beecher, later eclipsed Lyman’s own celebrity in the fight against slavery.

Lyman Beecher to Jonathan Huntting

December 4, 1805

Mid-Atlantic Early Manuscripts Collection (1974.002)

Brooklyn Historical Society