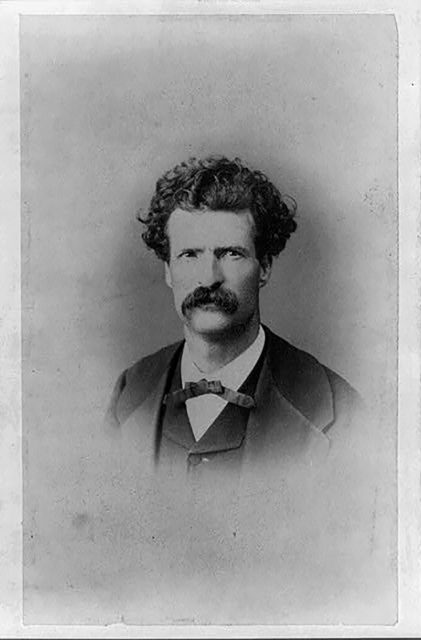

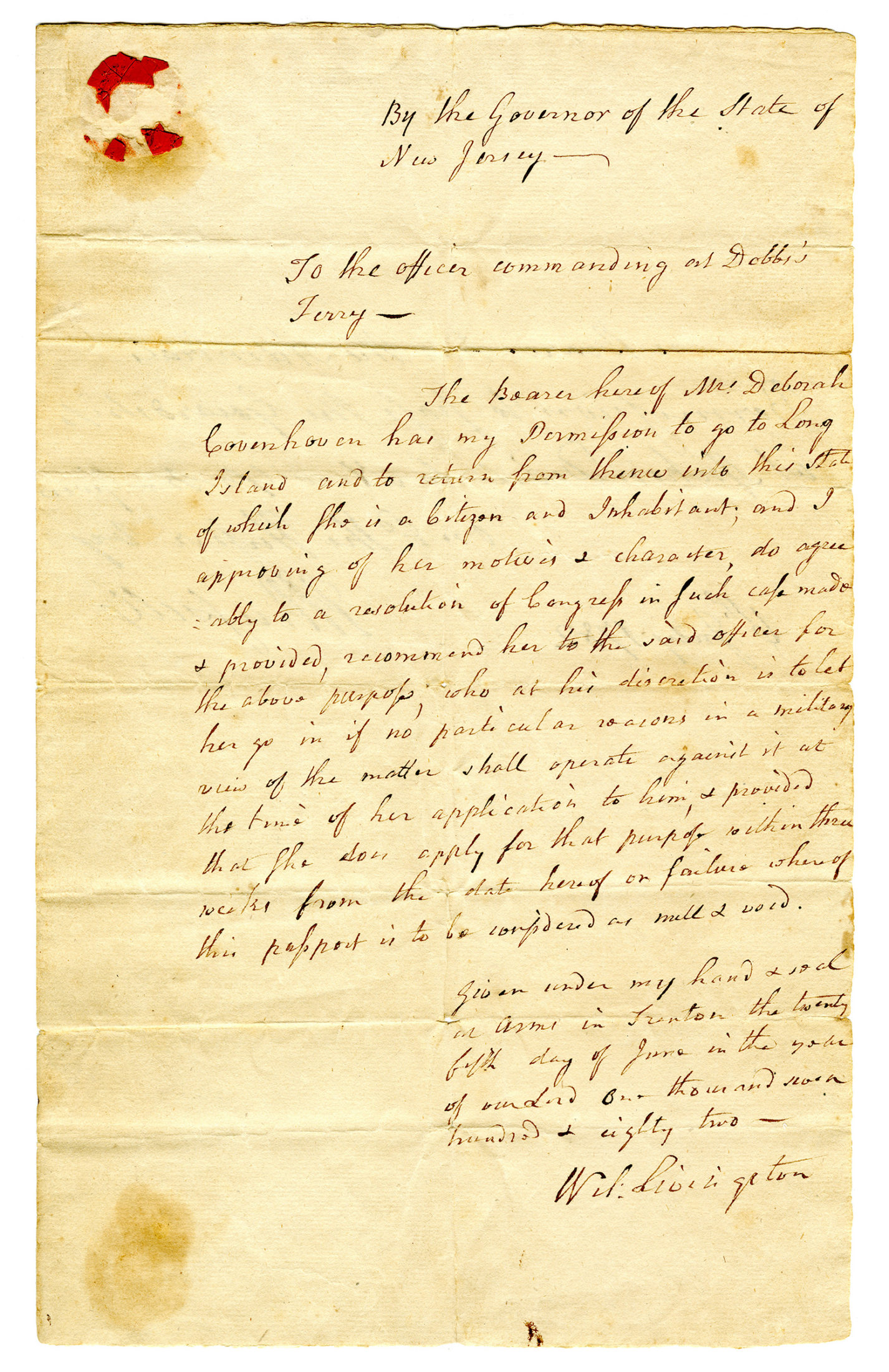

“Mr. B. preaches to seven to eight of his mistresses every Sunday evening”

The Tilton-Beecher Sex Scandal

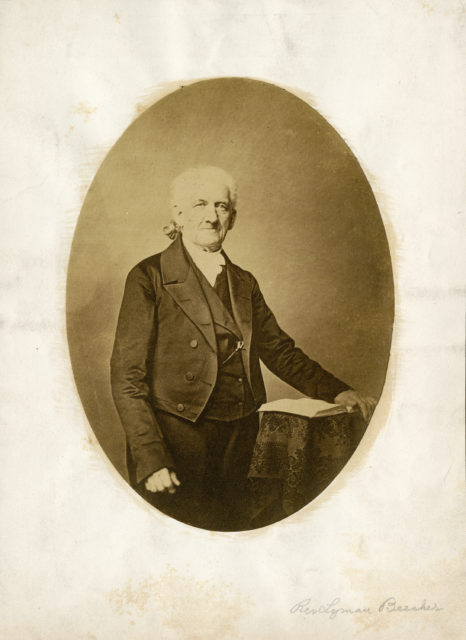

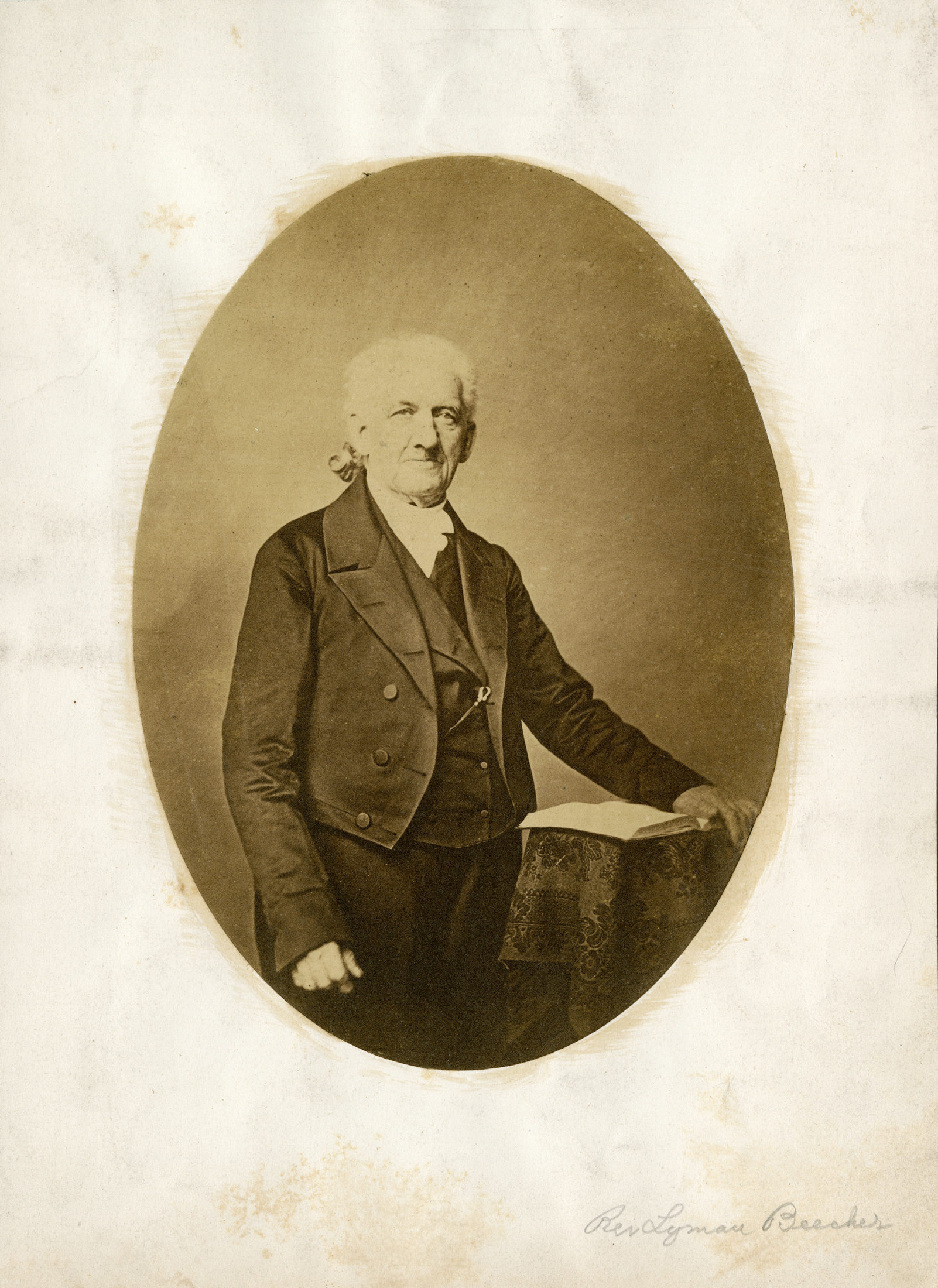

The love and respect that Plymouth Church congregants had for their Rev. Beecher led them to preserve this chair. It also guided their support of him throughout the public sex scandal that swept the religious leader and reformer into the national spotlight. In 1874, Beecher’s supposed affair with Brooklynite Elizabeth Tilton, wife of his longtime friend and protégé Theodore Tilton, became public. A national media firestorm tainted Beecher’s legacy with the suspicion of sin.

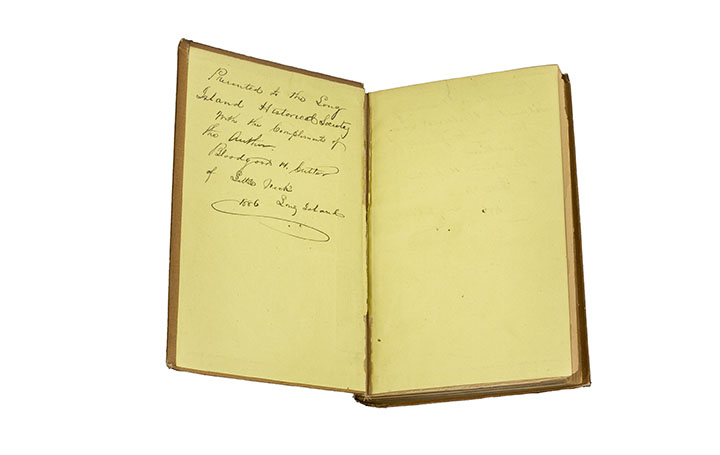

When Beecher accepted the pastorate at Plymouth Church in 1847, he brought to Brooklyn his wife of a decade, Eunice Bullard Beecher. His charisma and passion at the pulpit, which increased Beecher’s celebrity and endeared him to churchgoers, reportedly also attracted female admirers. In fact, before the sex scandal became national news, local gossip, circulated by whisper and in published accounts, claimed that “Mr. B. preaches to seven to eight of his mistresses every Sunday evening.”

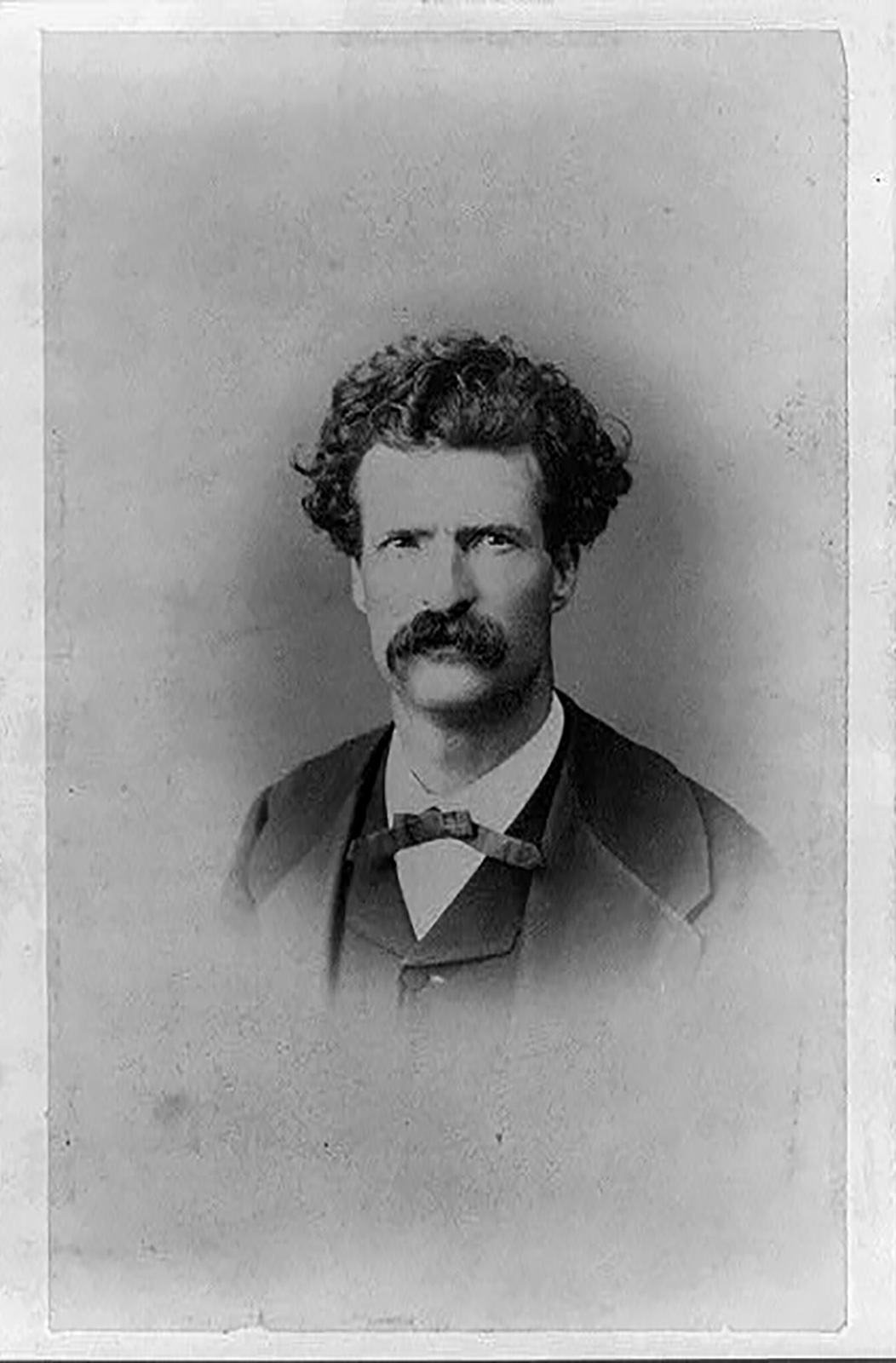

Mrs. Henry Ward Beecher, circa 1870

V1974.51.10

Brooklyn Historical Society

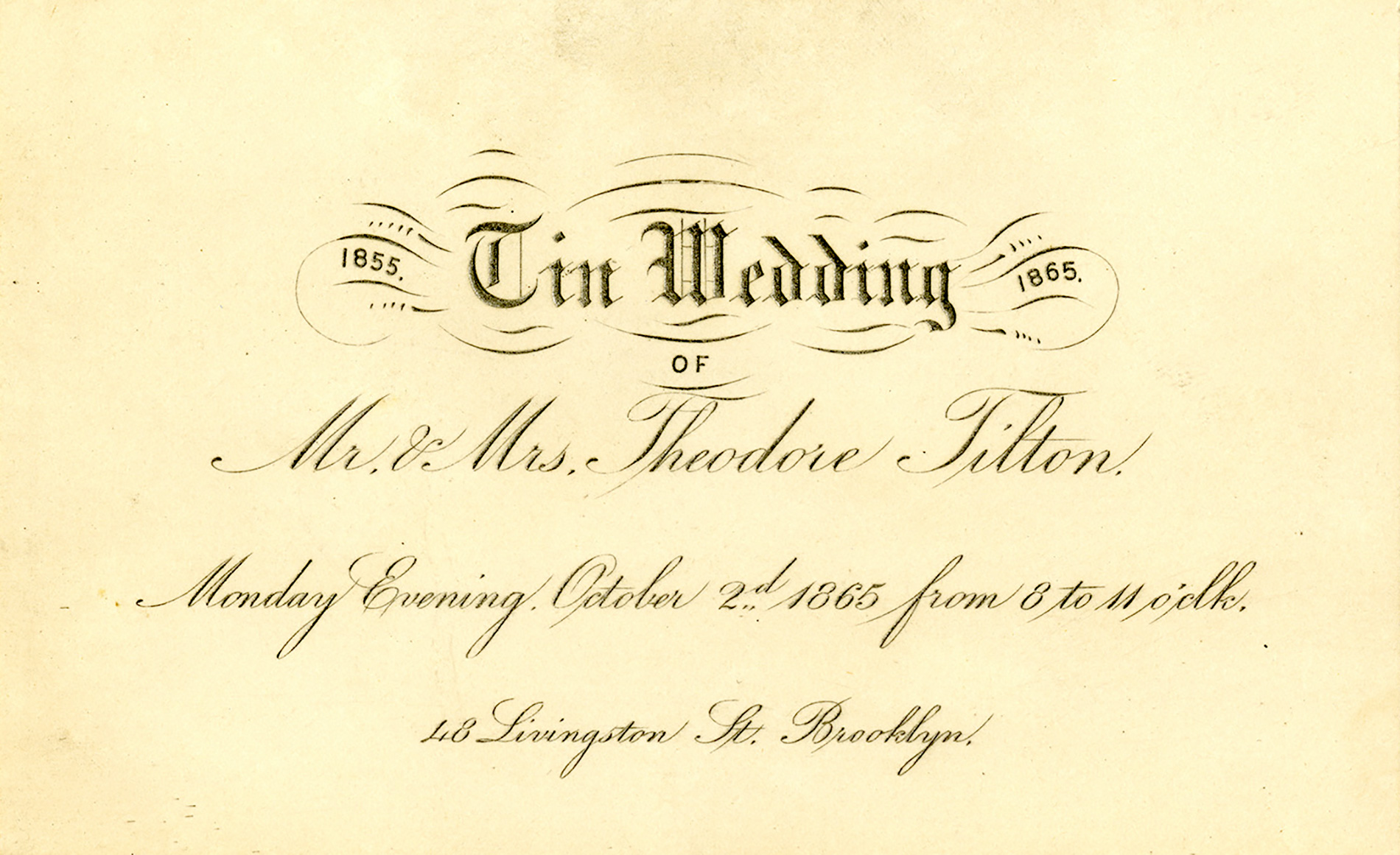

Elizabeth Tilton was among Beecher’s rumored paramours. Her supposed sexual relationship with Beecher, from 1868 to 1870, was the spark that grew into Beecher’s future adultery trial. While Theodore Tilton, Elizabeth’s husband, and Beecher had become confidants following Beecher’s arrival in Brooklyn, professional and political differences later put them at odds.

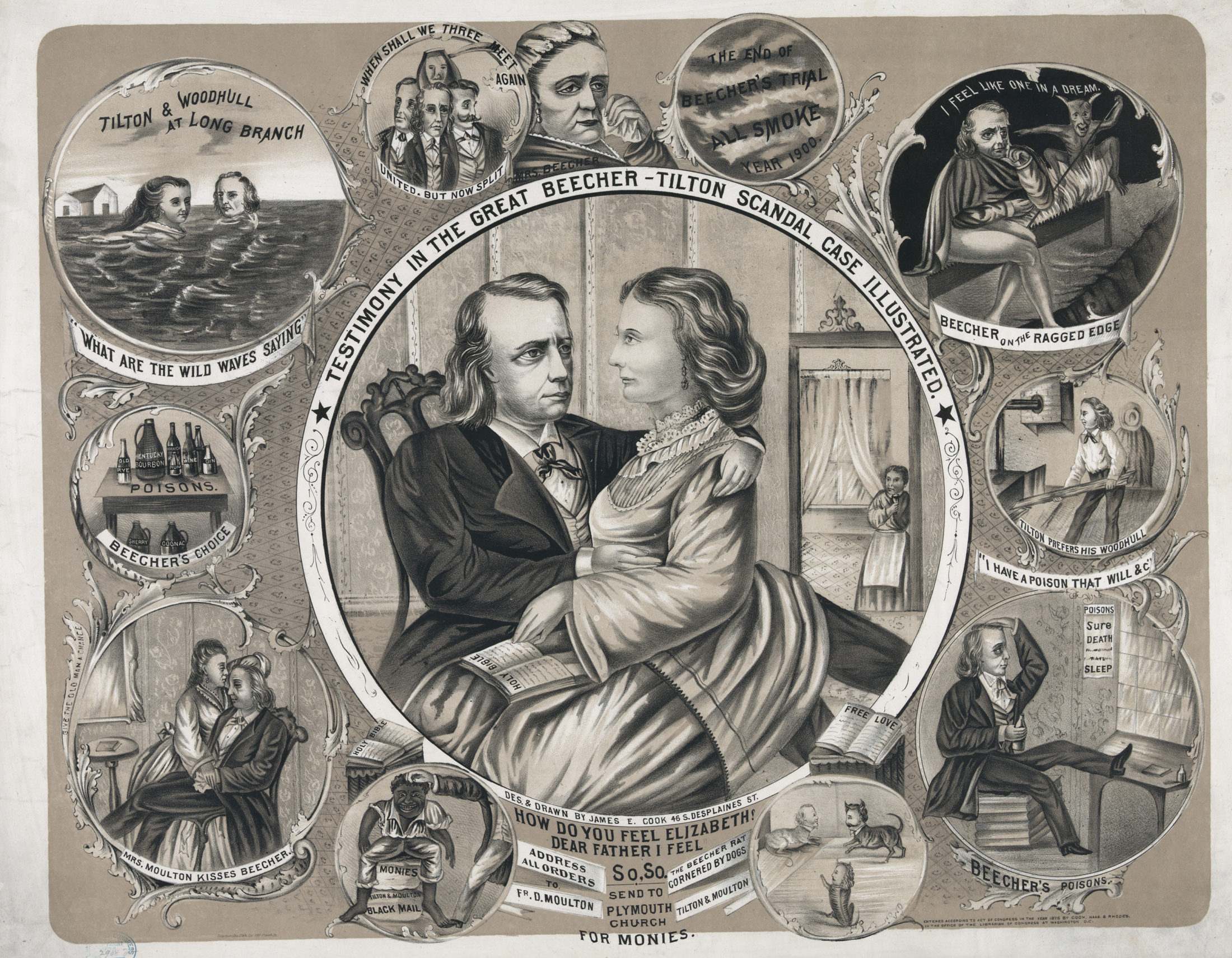

In late 1870, Elizabeth supposedly confessed the affair to her husband, only to recant and then recant her recanting. After confronting Beecher, Tilton negotiated a silence on the subject through a mutual friend, but the story nevertheless spread. In 1872, it reached spiritualist and reformer Victoria Woodhull. An ambitious supporter of women’s suffrage and marriage reform, and the first women to run for president, Woodhull exploited the rumors to bring attention to her causes. On October 28, 1872, she published “The Beecher-Tilton Scandal Case” in her magazine Woodhull & Clafin’s Weekly, launching the affair into the national spotlight.

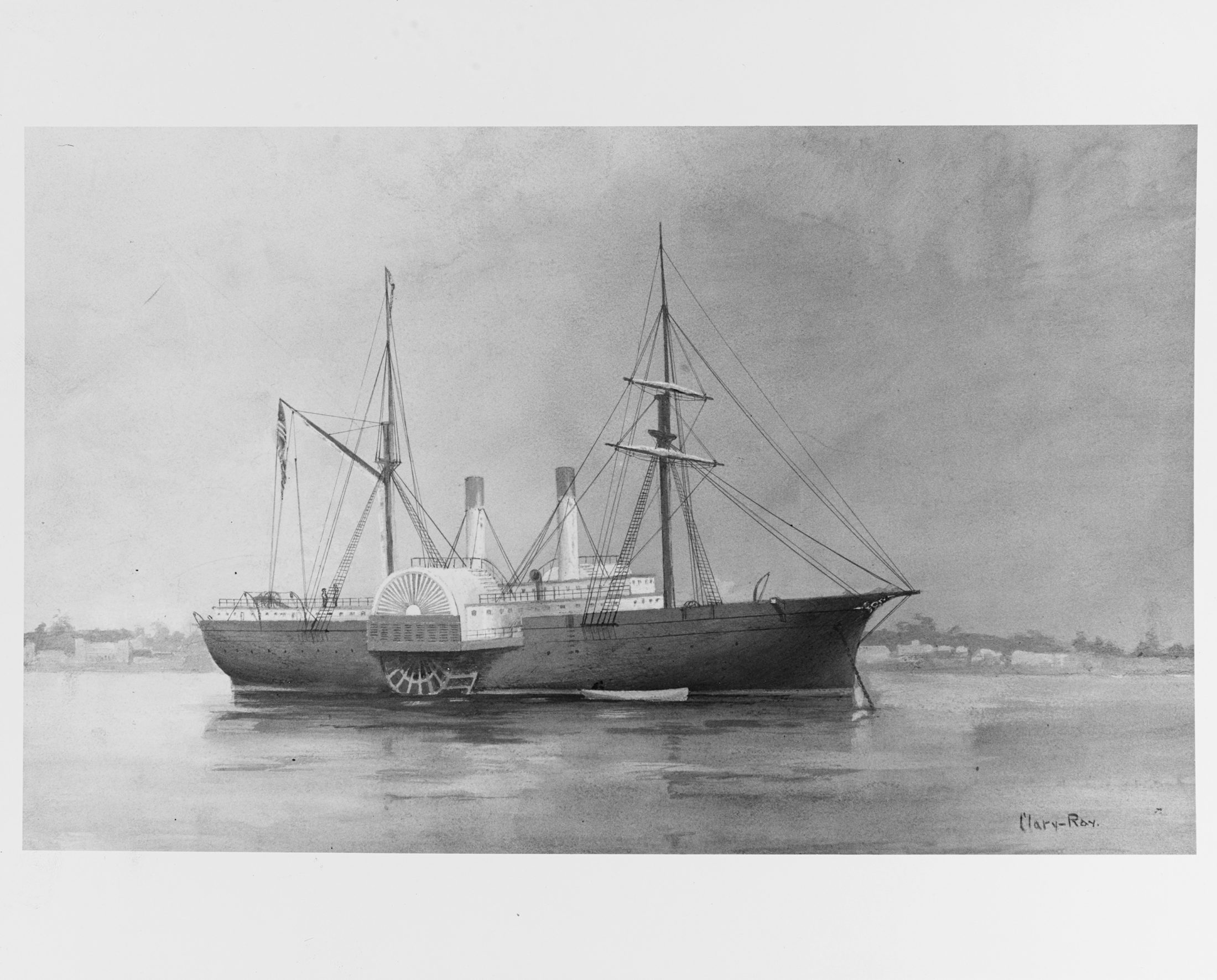

Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Tilton anniversary party invitation, 1865

Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims and Henry Ward Beecher collection (ARC .212)

Brooklyn Historical Society

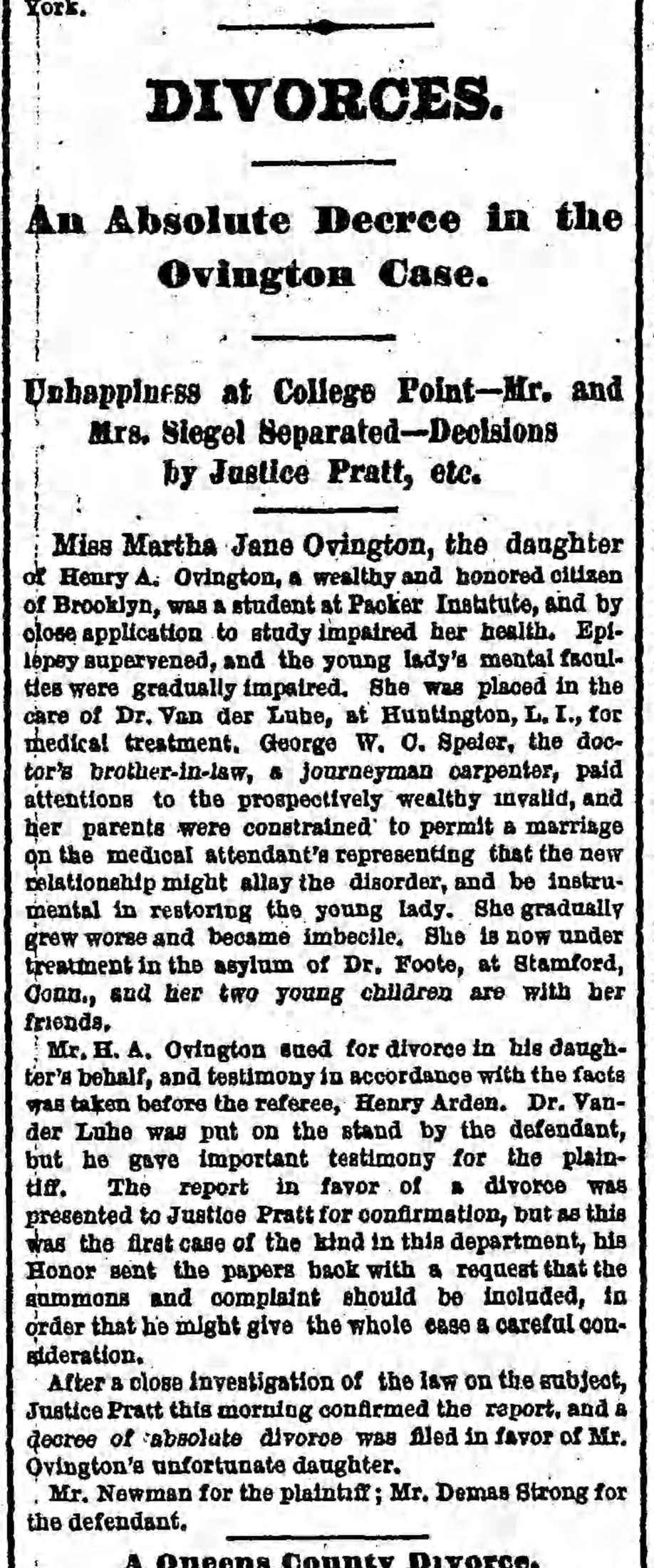

In the 1800s, calls for women’s suffrage and the more radical demands for marriage reform and access to divorce clashed with strict traditional Christian morality and gender roles. In New York, adultery was a legitimate cause for legal suit, which is what Theodore Tilton ultimately did. Theodore Tilton v. Henry Ward Beecher, Action for Criminal Conversation began in January 1875 and lasted six months, each day’s events meticulously reported by the press. In the end, the result was a hung jury, votes stalled at 9 to 3 in Beecher’s favor.

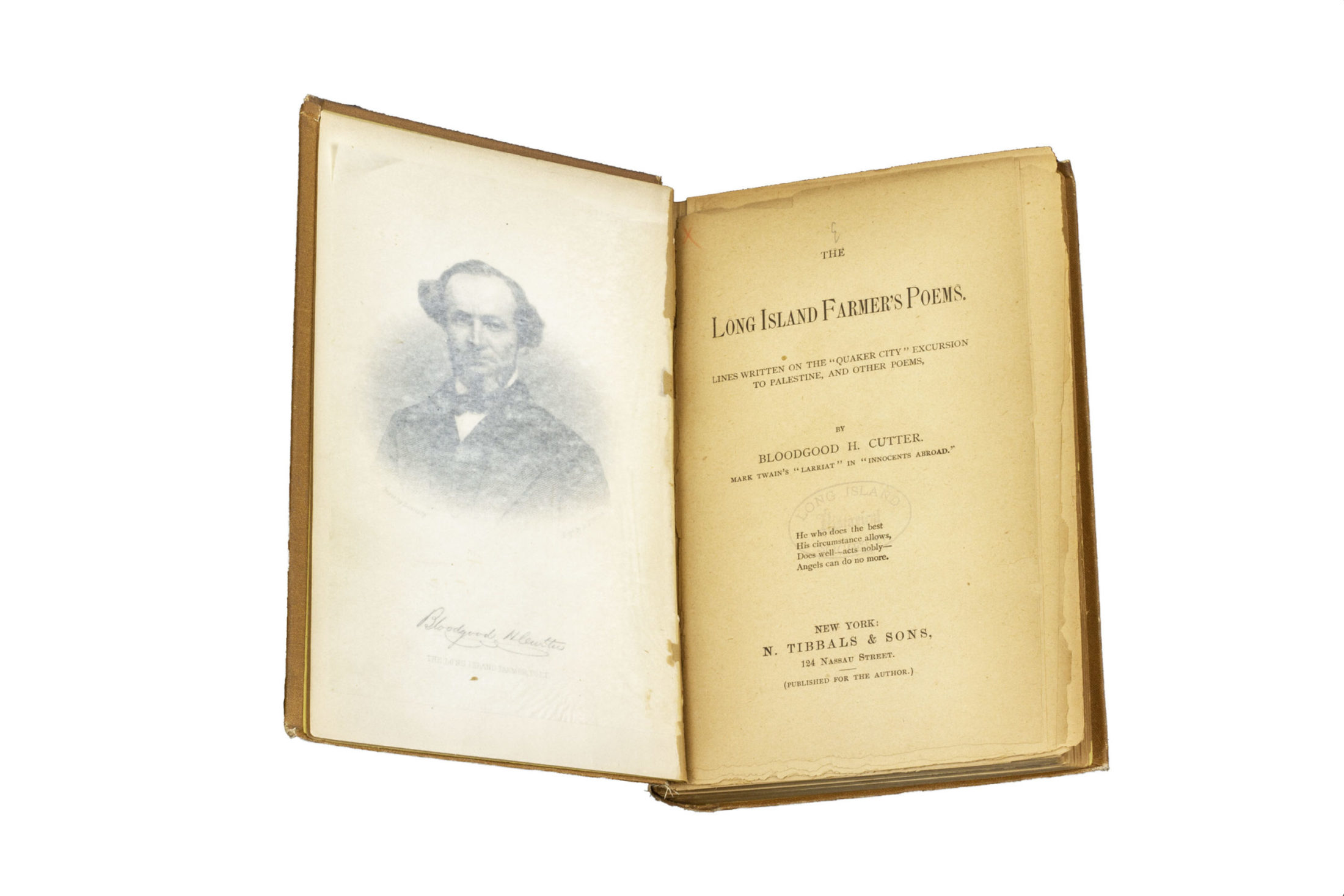

“Testimony in the Great Beecher-Tilton Scandal Case Illustrated,” 1875

Cook, Haas & Rhodes

Library of Congress

Beecher continued at Plymouth Church until his death in 1887, supported by his loyal congregation who banded together to raise money to help pay his legal fees. Despite the community support, questions about the affair persisted, especially after 1878, when Elizabeth Tilton published a confession of their guilt. Beecher may have been the most famous man in America during his life, but like many other powerful men, his legacy is marked by a sex scandal.