Broad, Boxy, and Rare

Long Island’s Early “Pilgrim Furniture”

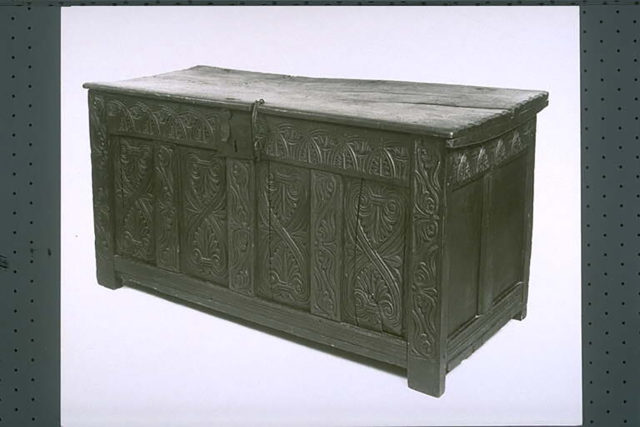

This slant-lid desk box, which dates from the mid-1600s, is among the earliest pieces of furniture in the BHS collection. A piece of “pilgrim furniture,” it is typical of the kinds of furnishings that the first generation of English settlers in North America desired for their homes. Modeled after popular contemporary English furniture, early pieces like the desk box are typically broad and boxy, sturdily constructed, and decorated with elaborate carvings.

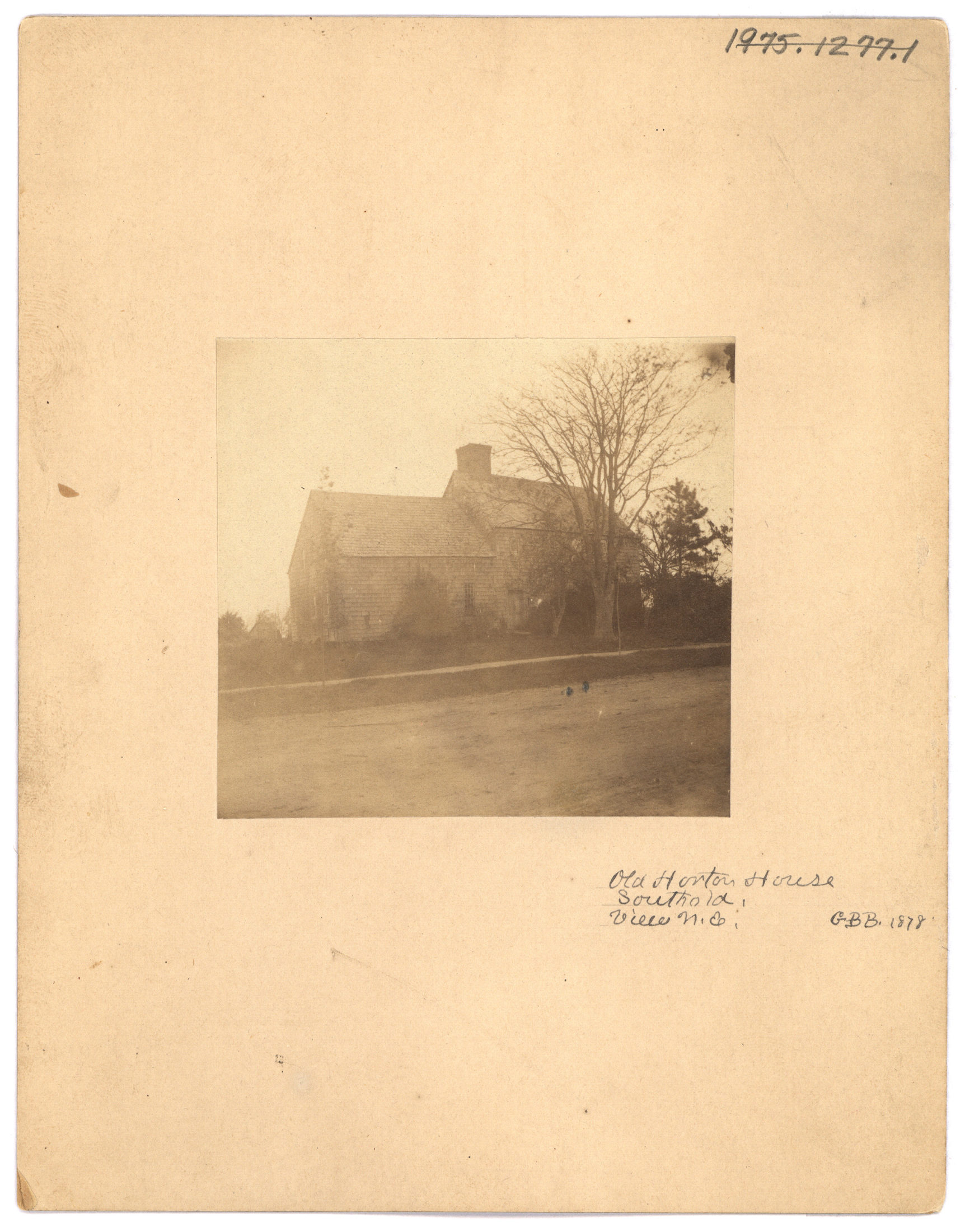

When a Wells family descendant donated the box to the Long Island Historical Society (now Brooklyn Historical Society) in 1887, they asserted that the box had been “brought from England by the first William Wells” of Southold, Long Island. Some immigrants did cross the Atlantic with their furnishings, including Southold’s Barnabas Horton, whose English-made red oak chest is also in the BHS collection. However, microanalysis of the wood used to make the Wells family desk box confirms it is of American manufacture. The box is made of post oak, which at the time was only available in New England.

Chest, 1620–40

M1985.346.1

Brooklyn Historical Society

The simple abstract carving decorating the desk box suggests a potential connection to Connecticut. A New Haven–made chest owned by Thomas Osborne of East Hampton, Long Island, in the 1600s shares a very similar carving style to that of the box. Furthermore, Wells traveled to Connecticut often as Southold’s deputy representative to the General Court of the New Haven Colony, to which the Long Island settlement pledged allegiance, making it possible that he commissioned his desk box from an area craftsman. The desk box’s stylistic connection to New England is just one example of the larger social and cultural ties that bound the towns of Long Island’s East End to their neighbors just across the Long Island Sound.

Chest, 1640–60

Probably made in New Haven, Connecticut

Home Sweet Home Museum, East Hampton, Long Island

Image courtesy the Winterthur Library, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection