Whose Faces Do We Remember?

Power, Privilege, and Slavery in Suffolk County

Commissioned portraits like Samuel Buell’s capture their subjects as they wished to be remembered, with their serene expressions and elegant clothing highlighting their respectability and affluence. Abraham G.D. Tuthill painted Buell in his black robes and preaching bands, depicting him as a religious leader and a pillar of his community. Buell’s public accomplishments support this image. He was a Revolutionary War hero who remained in East Hampton to defend the community. After the war, he helped establish East Hampton’s Clinton Academy, which opened in 1784 as one of the town’s first coeducational schools.

View of Clinton Academy, East Hampton, 1878

Elias Lewis Jr.

V1972.1.393

Brooklyn Historical Society

When examining portraits like Buell’s, it is important to consider not just what is depicted but also what was omitted. Like his fellow landowning neighbors throughout Suffolk County, Samuel Buell was a slave owner. Early English settlements like East Hampton were established in the mid-1600s. Their agricultural and maritime businesses required laborers, and enslaved labor quickly became the most profitable type. By 1698, nearly 22 percent of Suffolk County’s population was of African American descent and nearly all were enslaved.

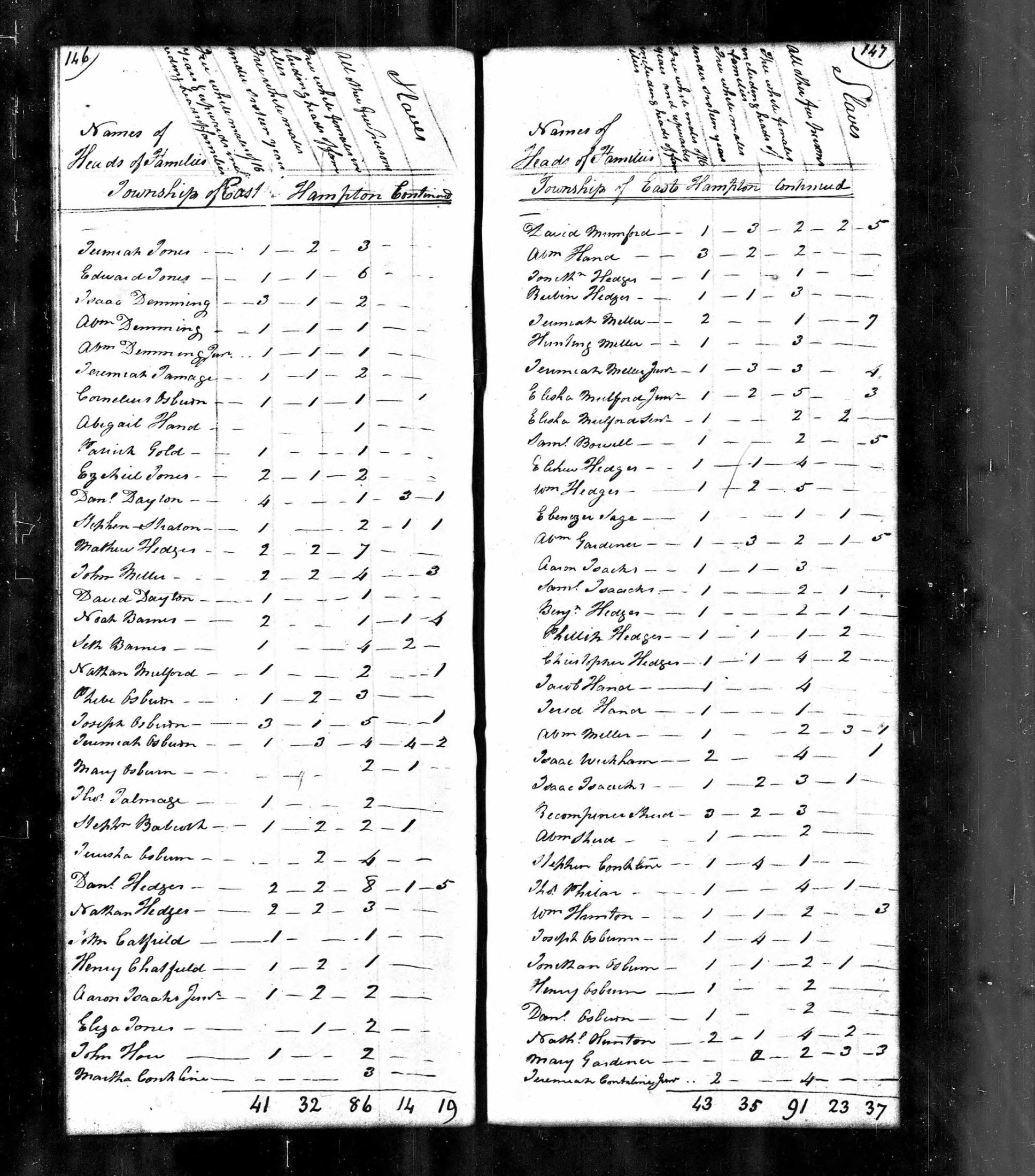

By the late 1700s, most of Suffolk County’s slaveholding households had only one or two enslaved people. It was a rarity for Suffolk County families to own more than two people. The 1755 census shows three enslaved persons in Buell’s household; the 1790 federal census, the first of its kind, documents an increase of that number to five, marking Buell as one of the county’s most prolific slaveholders.

Federal census entry for Samuel Buell, 1790

United States Census Bureau

National Archives and Records Administration

When he died in 1798, Buell left instructions in his will to manumit—or legally free—three enslaved laborers, Jree, Eber, and Prine. He also stated that the three men would earn their freedom only after serving long mandatory indentures to Buell’s family members. For example, Eber would only become free after he served “Mrs. Buell until eighteen years of age and then to be sold for seven years and that at twenty-five years of age to commence free from servitude if he behaves well if not to serve a year or two longer.” Eber’s was a rocky path to freedom. Like the rest of New York state’s enslaved population, Buell’s enslaved laborers may not have been legally free until 1827, when New York’s gradual emancipation law took effect.

Enslaved laborers laid the foundation for Samuel Buell’s legacy, but very few references or artifacts documenting their existence survive. As a result, objects like Buell’s portrait and its representations of his wealth must stand in to remind us of enslaved peoples’ contributions to the history of Long Island.