“When Mr. Beecher sold slaves in Plymouth pulpit”

Henry Ward Beecher’s Abolitionist Slave Auctions

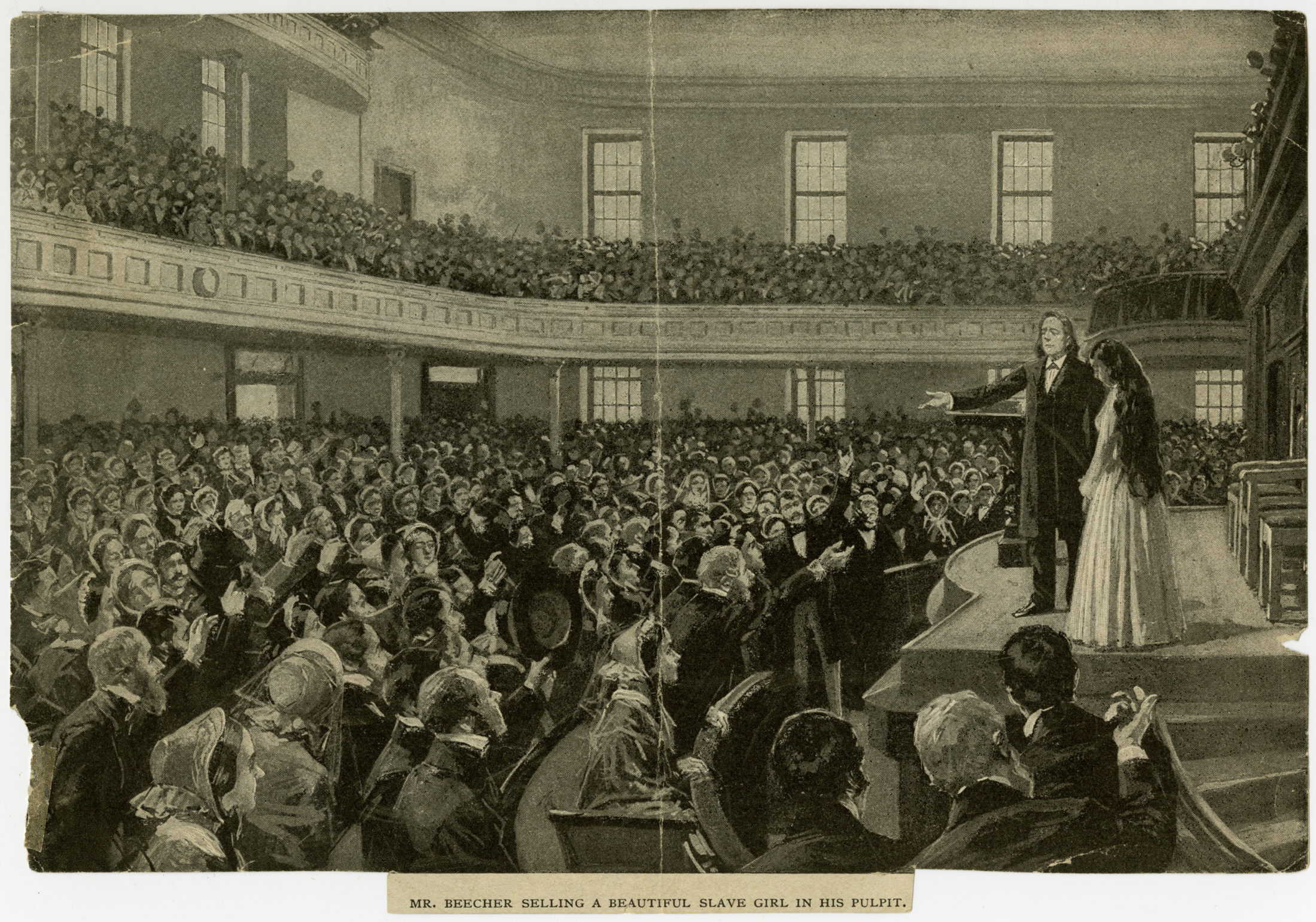

From his pulpit at Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church, Henry Ward Beecher became a leading voice against American slavery. Through passionate sermons, popular lectures, and essays, Beecher exposed Northern audiences to the cruelties of the practice that many chose to ignore. Beecher was known for his flair for the dramatic. This pulpit chair was in use at Plymouth Church during Beecher’s most shocking anti-slavery spectacles: his mock slave auctions of the 1850s and early 1860s.

These events were essentially theatrical fundraisers that coopted the format of the auction block to expose Beecher’s amassed audiences to the cruel spectacle of slavery. Always featuring young, typically light-skinned enslaved women and girls, these events promoted an “acceptable” form of blackness that allowed Beecher to lambast slavery while also raising the money needed to purchase the freedom of the featured women.

“Mr. Beecher selling a beautiful slave girl in his pulpit,” circa 1896

Thure de Thulstrup

V1973.6.523

Brooklyn Historical Society

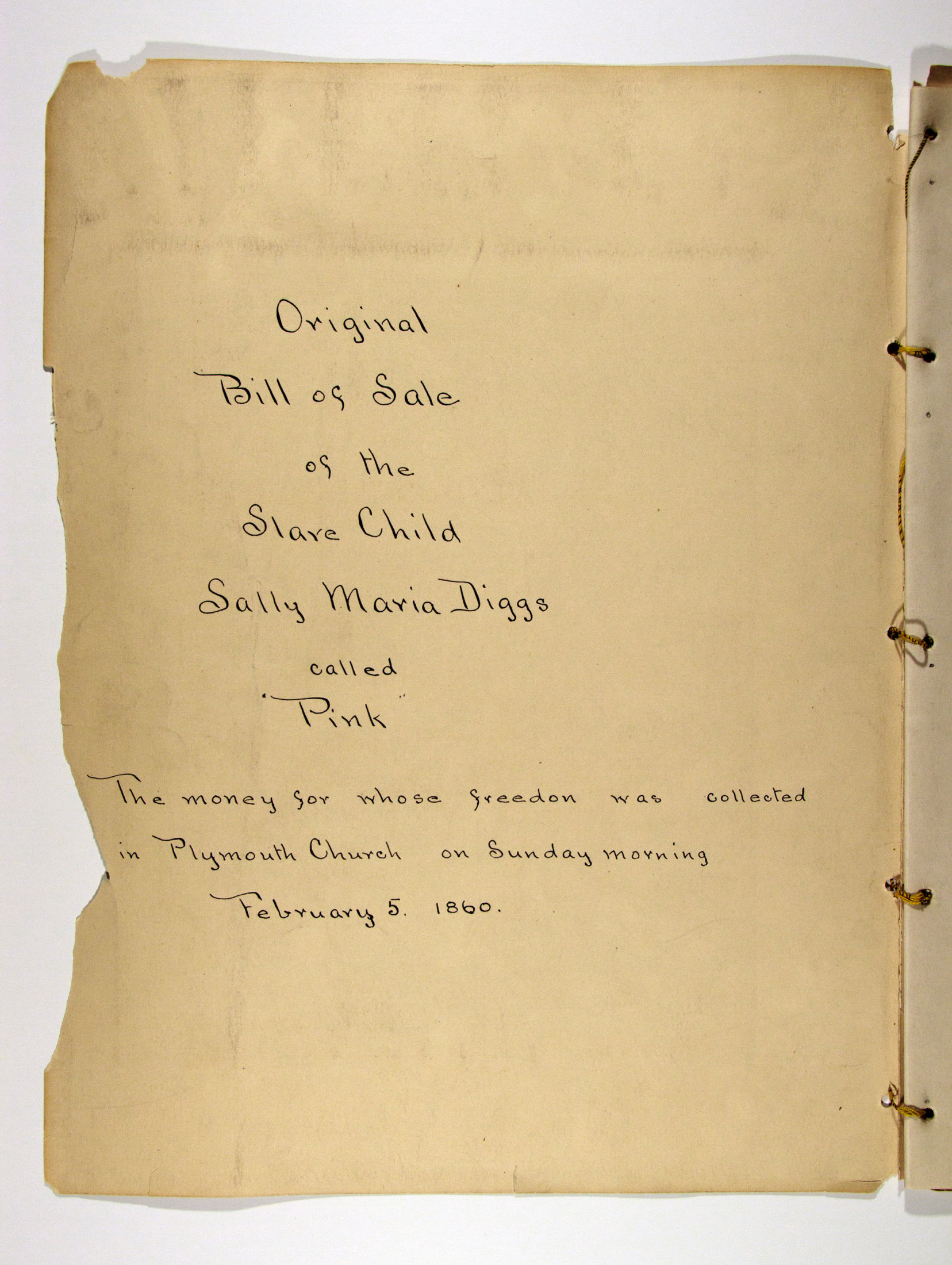

Plymouth Church held at least six public “auctions” before the end of the Civil War. The sale of Sally Marie Diggs in 1860 left a lasting impression on Beecher’s congregation. Diggs, an enslaved nine-year-old born just outside Washington D.C., was brought to Beecher’s attention by Virginia Rev. John Falkner Blake as a worthy candidate for Beecher’s next auction. A surviving bill of sale in the BHS collection shows that Blake purchased Diggs from her enslaver, John C. Cook, for $900. The funds that Beecher raised purchased Diggs’ legal freedom from the Reverend Blake.

Sally Marie Diggs bill of sale, 1860

Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims and Henry Ward Beecher collection (ARC.212)

Brooklyn Historical Society

Beecher’s congregation raised more than $1,000 to purchase Diggs’ freedom. For the young girl, the event was a significant and complex moment in her life. She earned her freedom, but only after her mother and sisters had been sold by their enslaver, separating the family forever. Beecher christened Diggs with a new name, Rose Ward, combining a part of his name with that of one of his parishioners, Rose Terry, who contributed a ring to the collection to purchase Diggs’ freedom.

Although the act of purchase and patronage stripped her of her previous identity, Rose Ward persevered in her new life with her new name. After the auction, she returned to Washington, D.C. with her grandmother, Chloe Diggs, where she worked as a seamstress before attending Howard University, a historically black college. While in college, Ward met her future husband, James Hunt.

Ward returned to Brooklyn only once, in 1927, for the eightieth anniversary celebration of Beecher’s first sermon at Plymouth Church. A selection of her remarks to the congregation at the celebration were recorded on a wax cylinder—an early form of sound recording—that survives today in the BHS collection. Rose Ward’s intertwined history with those of Beecher and Plymouth Church is a reminder today that Brooklyn was a key battleground in the complex negotiation of slavery and racism in America.

Henry Ward Beecher and ‘Pinky,’ circa 1930-1932

Photograph after the original painting by Harry Roseland

V1974.39.51

Brooklyn Historical Society

MISSING IMAGE

[F10 tombstone]

Rose Ward Hunt wax cylinder, 1927

Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims and Henry Ward Beecher collection (ARC.212)

Brooklyn Historical Society