“We set off for Long Island”

Witnessing Tragedy in Early Breukelen

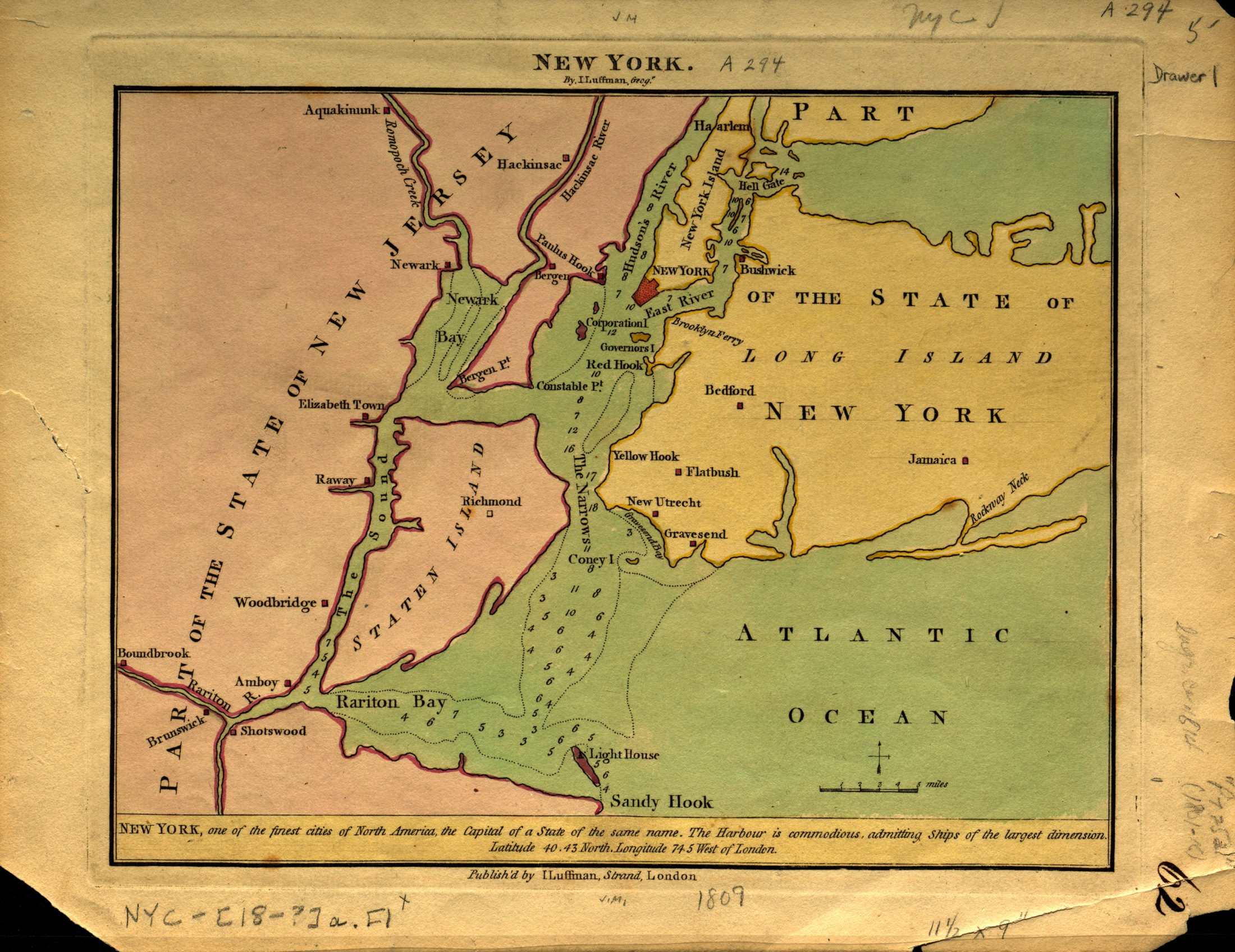

When they crossed the East River in 1639, Anthony Van Salee and his family were among the first European settlers to establish permanent homes on Long Island, New Amsterdam’s neighboring frontier. The first purchase of land in western Long Island had taken place just three years earlier, by Dutch West India Company officer Jacob Van Corlaer.

More people followed. The Dutch government approved the incorporation of several towns: Gravesend (1645), Breucklen (Brooklyn, 1646), Flatlands (1647), Flatbush (1651), New Utrecht (1657), and Bushwick (1660). Van Salee’s land eventually fell near the two most southernmost villages, Gravesend and New Utrecht.

New York, 1809

I. Luffman Strand

NYC-[18-?]a.Fl

Brooklyn Historical Society

The lands that individuals like Van Salee claimed as their own were not unoccupied. Long Island was part of the territory of the Lenni Lenape, American Indian communities who called the island Sewanhacky and lived along its waterways. Little information survives today about Lenape life in the 1600s. Limited archaeological evidence and European accounts, which must be scrutinized with a critical eye for bias, provide few details about their lives.

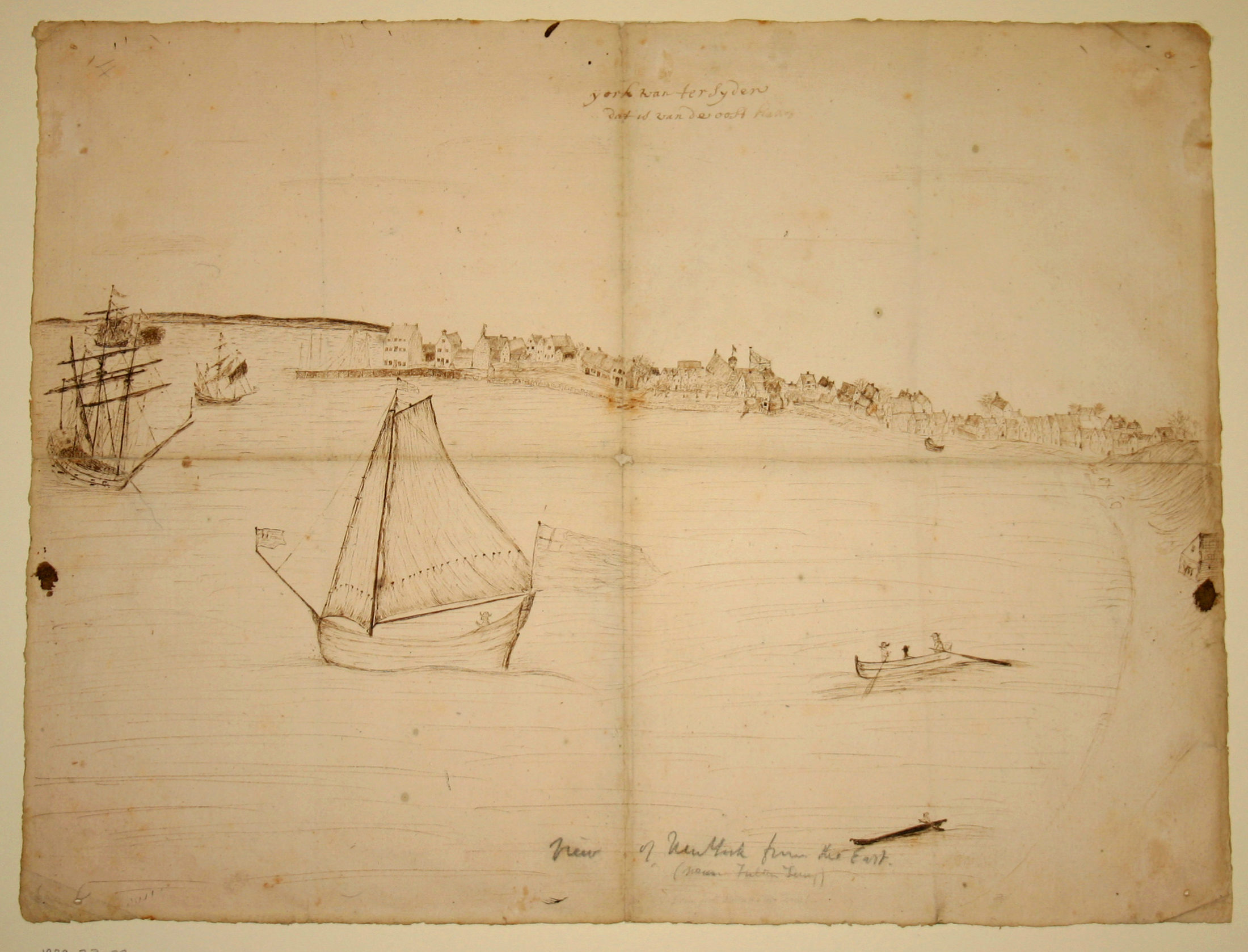

View of New York from the North (near Fulton Ferry), 1679

Jasper Danchaerts

M1979.23.4

Brooklyn Historical Society

Dutch Labadist priest Jasper Danckaerts visited New York and Long Island in 1679, part of an extensive journey across North America in search of a potential location to establish his religious sect. He kept a detailed dairy of the trip, beginning from the moment of his departure from Holland, at 4 a.m. During the journey across the Atlantic, Danckaerts became acquainted with some New York residents, including Gerrit Cornellissen Van Duyn, who made introductions for Danckaerts in Manhattan and Long Island when they arrived in September 1679.

Bentwood Box, 17th century or later

M1984.320.3

Brooklyn Historical Society

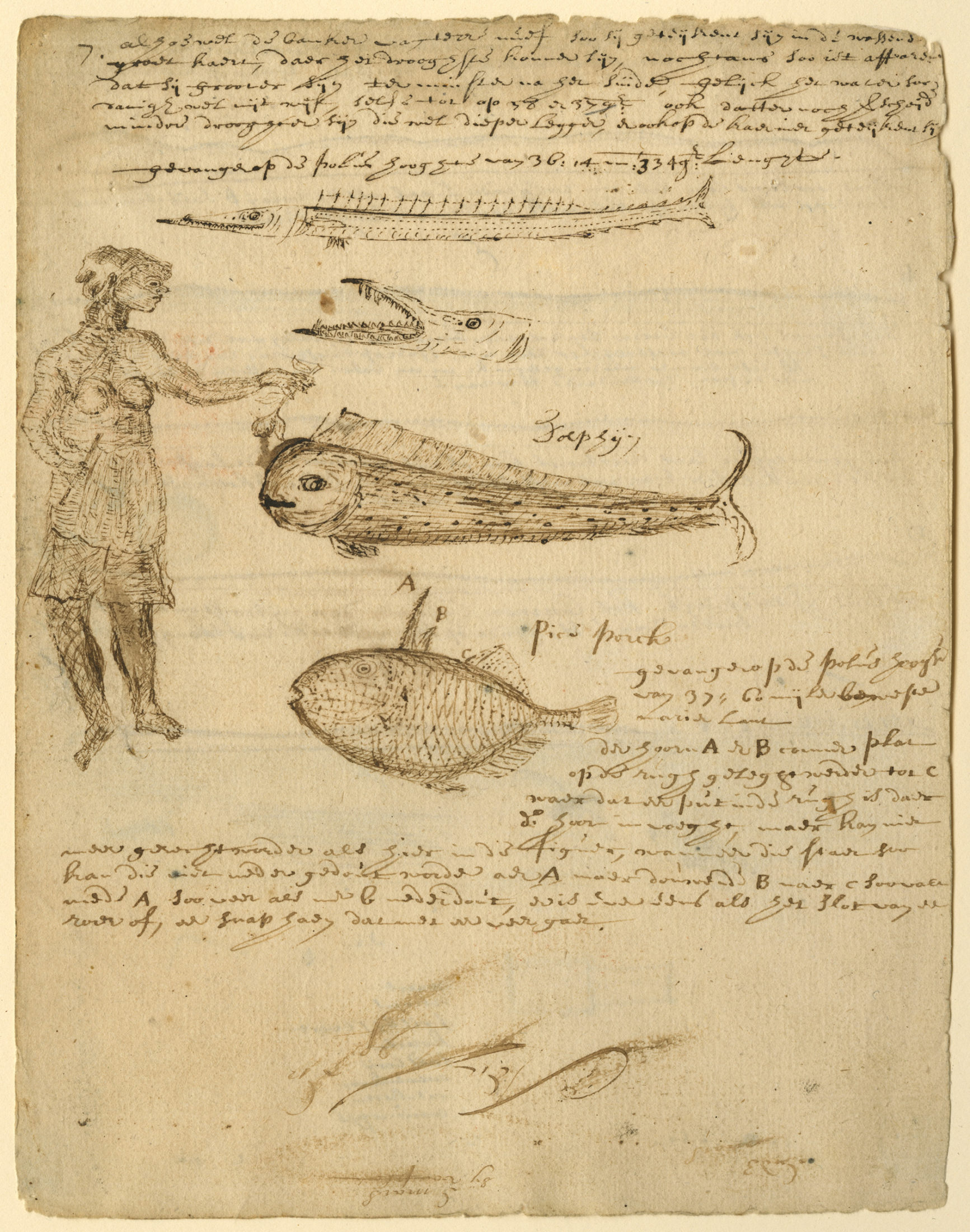

Invited into an American Indian longhouse, Danckaerts recorded with interest details of the building’s structure and the family dynamics and meals. His accounts also include glimpses into the misunderstandings that had devastated the Lenape population by the end of the century. Danckaerts noted conflicting understandings about land ownership between Van Duyn’s brother-in-law and the local Lenape from whom he had purchased “the whole of Najack.” Jacques Cortelyou, Van Dun’s brother-in-law, considered himself the sole owner of this land. His indigenous neighbors continued working certain farm plots, a sign to them that the land was communal. On a visit to a neighboring Indian settlement, Danckaerts saw many children sick with smallpox, “the most prevalent disease in these parts, and of which many have died.” We know now that the Lenape did understand the power of land purchase, but they did not realize the reach of English and Dutch power and their control over these land deals.

American Indian woman with fish, 1689

Jasper Danckaerts

M1979.23.1

Brooklyn Historical Society

By 1684, mere years after Danckaerts’ visit to the region, the last of American Indian land in Brooklyn had been “transferred” to European settlers by American Indian sachems. Loss of land, European diseases, and warfare decimated the American Indian population by the late 1600s, reducing it to perhaps one-thirtieth of what it had been in the 1630s.