“The Young Lady’s Mental Facilities Were Gradually Impaired”

“Melancholia” in 19th-century America

Martha J. Ovington died on June 22, 1882, at age 41 and was buried at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. Cemetery records note epilepsy as “Mattie’s” cause of death. New research into public and private records reveals the tragic story of Ovington’s long struggle with physical and mental health, struggles that America’s then fledgling public health system was ill-equipped to manage.

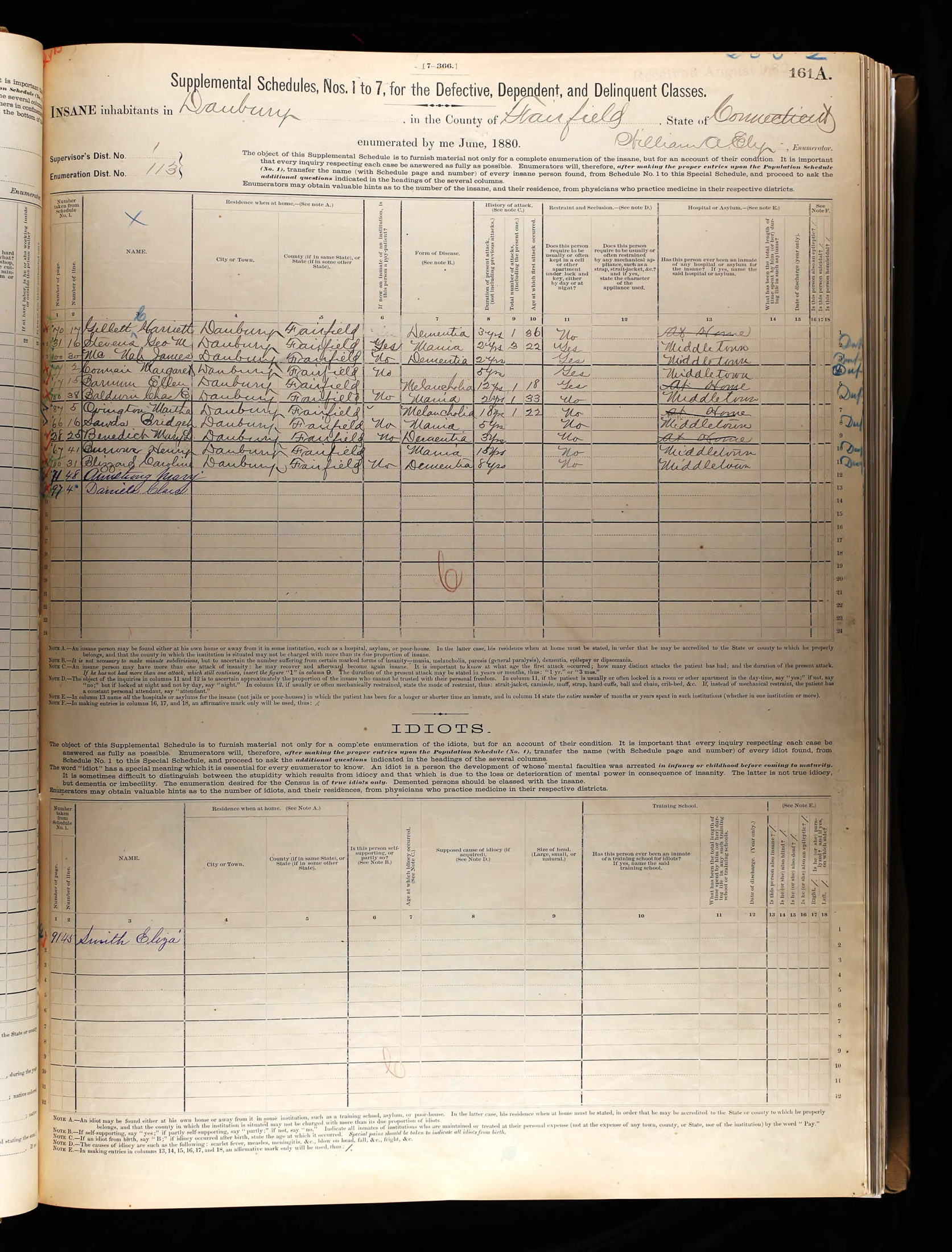

Unlike many other affluent young women in the 1800s, Ovington left behind no known personal documents recording the details of her daily life. However, public records like the 1880 federal census reveal unexpected information about her life. Ovington’s name is listed that year in the census’s new supplemental section for documenting the “defective, dependent, and delinquent classes.” Under “form of disease,” her illness is described simply as “melancholia,” or depression, from which she had apparently suffered for eighteen years.

Federal census Supplemental Schedule for “Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent” classes, 1880

United States Census Bureau

National Archives and Records Administration

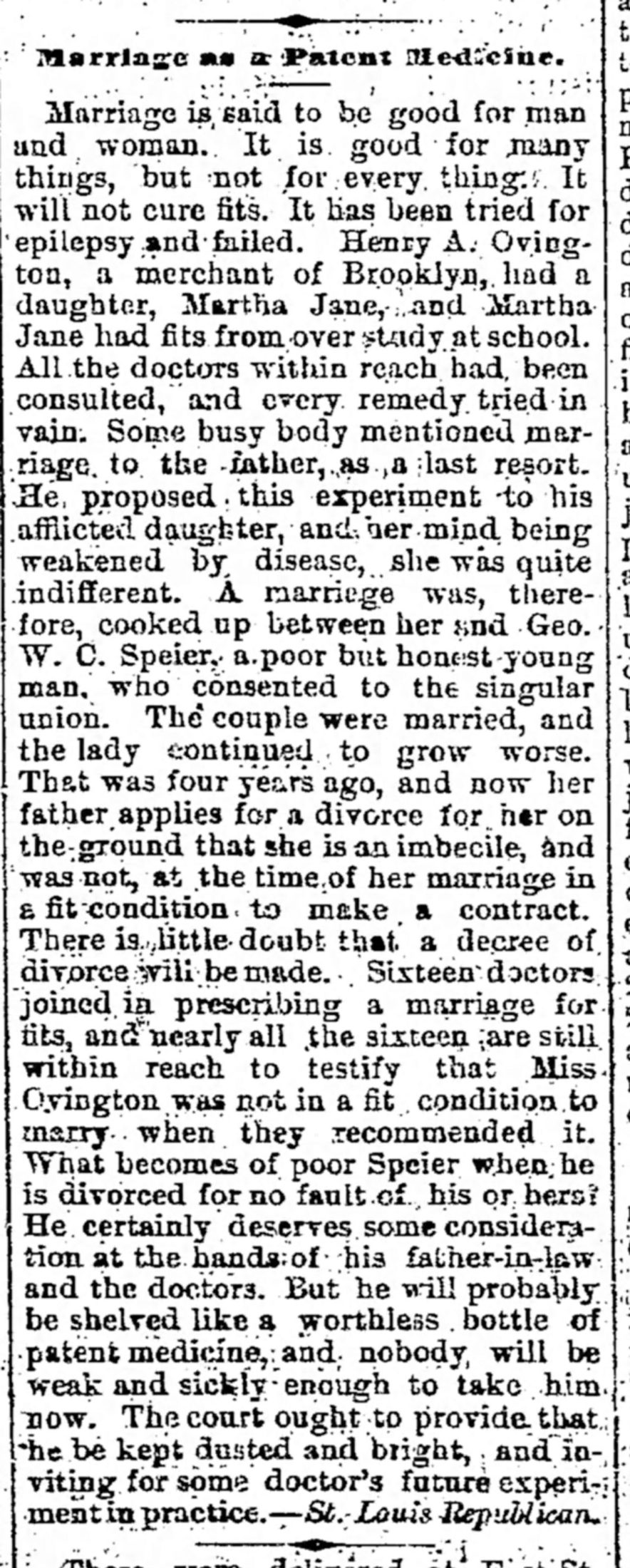

While modern audiences might assume that sensitive personal details like these would have remained largely private, the Ovington’s prominent family brought Martha’s struggles into the national spotlight. In July 1874, New York–area newspapers began running stories about a local divorce scandal. Brooklynite, Henry A. Ovington, Martha’s father, had been granted a divorce on his daughter’s behalf.

The articles note that Martha’s “mental faculties” had supposedly declined following her overexertion as a student at Packer Collegiate Institute. Following Martha’s graduation, her parents sent her to Huntington, Long Island, for medical treatment, where Martha met a Mr. George Speier. The family agreed to let the couple marry, believing that domestic stability might “allay [Martha’s] disorder.”

By 1874, however, Martha’s condition had deteriorated. Her parents ended the marriage and took in the couple’s two young children, one of whom, Florence, would later donate her mother’s Civil War flag to LIHS (now BHS).

“Marriage as a Patent Medicine”

Galveston Daily News, July 17, 1874

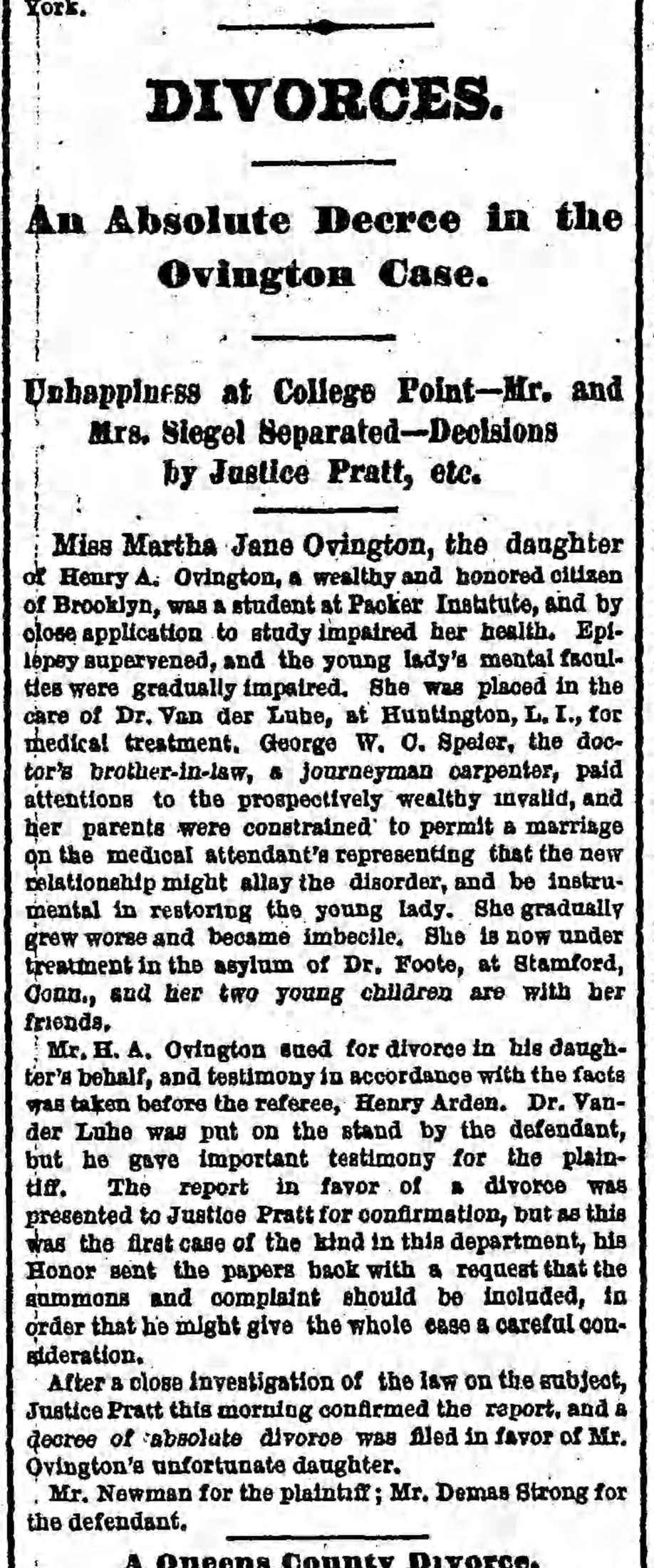

“An Absolute Decree in the Ovington Case”

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 6, 1874

Brooklyn Public Library

Records indicate that Martha was likely never formally institutionalized but rather had access to private care overseen by a physician or caregiver, which her family resources made possible. For those who could not afford private care, specialized care in mental hospitals—commonly known as asylums, then—became available in the United States beginning in the early 1800s, with numerous state-funded institutions built throughout the century.

Poor & Insane Asylum, 1878

George B. Brainerd

Early Brooklyn and Long Island photograph collection (V1972.1.34)

Brooklyn Historical Society