The World at Your Fingertips

Early America and its Global Connections

American founding fathers of color like Anthony Van Salee broaden our understanding of the first generation of European immigrants to North America. Their lives also contextualize American history within the broader history of globalization in the 1600s.

Anthony “of Salee,” born in northern Morocco, reached New Amsterdam in 1629, but global influences reached colonial America through more than just the movement of people and knowledge. Consumer goods also tied these frontier communities to the world through long-distance social and economic connections.

Dagger and scabbard, 18th or 19th century

M1991.890.1a-c

Brooklyn Historical Society

This dagger and scabbard, part of the LIHS (now BHS) collection since 1885, may have once belonged to Peter Stuyvesant (1612–72), last Dutch governor of New Amsterdam. In the late 1800s, the potential connection to a powerful male historical figure made this object valuable enough to save despite a lack of evidence to support the story. Today, the dagger’s ability to link colonial America to a diverse global economy is more compelling.

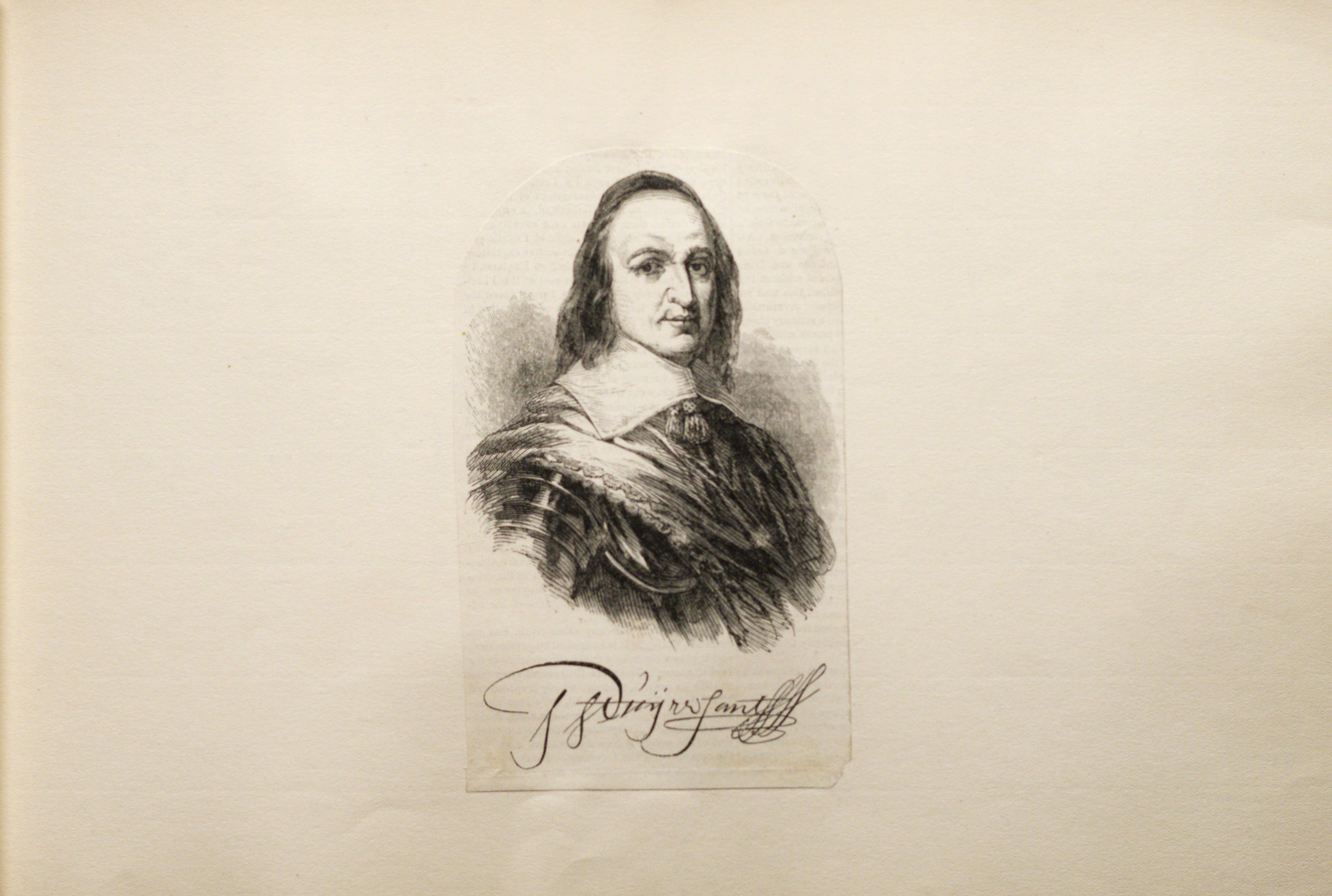

Peter Stuyvesant, 1907

“Bushwick and her Neighbors Vol. 1” scrapbook

Eugene L. Armbruster photographs and scrapbooks (ARC.308)

Brooklyn Historical Society

Wear on the dagger’s curved blade and the Turkish inscription indicate it was once part of a yatagan, a curved Turkish short sword. In the 1600s and 1700s, the powerful Ottoman Empire was renowned the world over for its technological prowess in mining and metalworking. The blade’s history indicates it was later altered by New York City silversmith Hugh Wishart, who worked in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Therefore, the dagger in its current form was likely not Governor Stuyvesant’s, who died in 1672.

Yatagan, 1600–1799

NG-NM-7110

Rijksmuseum, Holland

Creamer, circa 1800

Hugh Wishart

33.120.316

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The faded inscription on the dagger’s blade is the likely inspiration for the apocryphal connection to Stuyvesant. It reads something akin to “this sword…will take the revanche…of the enemy.” Prior to the dagger’s donation to LIHS, someone must have translated the inscription and assuming Stuyvesant, assuming that he harbored a desire for revenge for his “stolen” colony.

Fanciful story or not, the dagger’s blade provides evidence of the global movement and exchange of people, knowledge, and goods that shaped the culture of the Americas.