“The interesting and distinguishing beauty of Long Island”

Preservation of the Picturesque Retreat

In the late 1800s, urban pleasure-seekers began discovering eastern Long Island. Many learned of the region’s beauties through publications like Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, whose 1878 article “Around the Peconics” took readers on a rambling journey across the island, from Coney Island in the west all the way to Montauk Point. The author marveled at its beaches and bays, animal and plant life, and eastern Long Island’s remote upper and lower “forks” just east of Peconic Bay in Suffolk County.

Shore at Rocky Point, L.I. near East Marion, 1878

George B. Brainerd

V1972.1.140

Brooklyn Historical Society

The writer of the article also introduced his readers to the island’s villages, “clean and bright with new paint and prosperity.” He was fascinated by the region’s historic houses and their massive chimneys, writing that the “interest and distinguishing beauty of Long Island…lie in its antiquity and the traces of the memorable past which have survived.”

Interior of the Payne House, East Hampton, 1870

John Mackie Falconer

M1974.156.1

Brooklyn Historical Society

That eastern Long Island was “as pretty a picture of rural comfort as the tired city man can well imagine” attracted the interest of urban dwellers and land developers hoping to build getaways for New Yorkers and Brooklynites living in increasingly crowded cities.

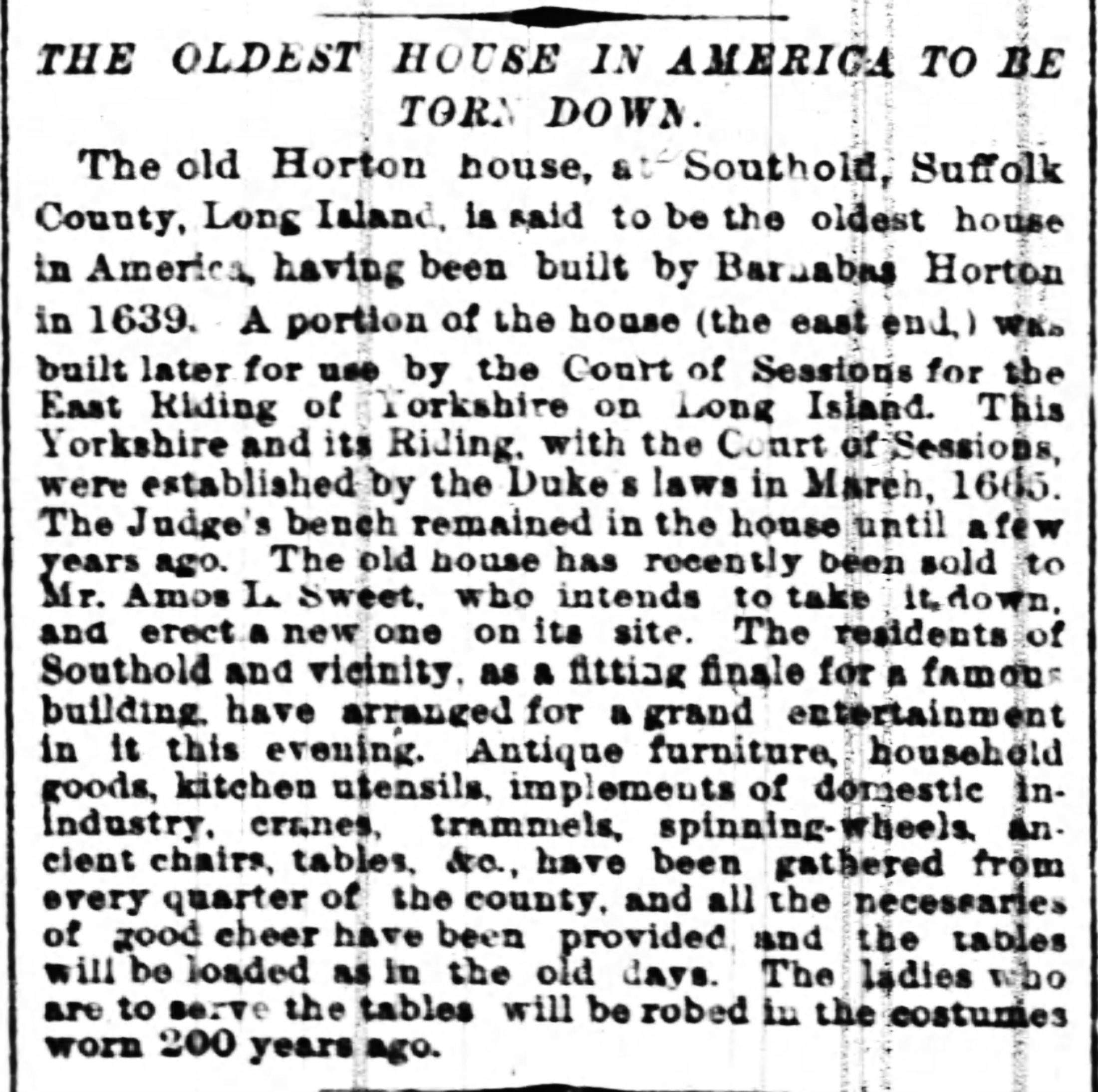

This interest from urbanites in Long Island resulted at times in the destruction of treasured local historic structures. For example, the demolition around 1878 of the Old Horton House made national news. Described as “the oldest house in America,” the house dated back to the 1660s, when it was built by Barnabas Horton (1600–80), one of the original settlers of Southold, Long Island. This steady loss of local history spurred many to action.

Old Horton House, Southold, 1878

George B. Brainerd

V1972.1.42a

Brooklyn Historical Society

“The Oldest House in America to Be Torn Down”

New York Times, October 22, 1878

When the Long Island Historical Society opened in 1863, it was the first institution of its kind on the island. Many of LIHS’s earliest members lived in Queens and Suffolk counties. Witnessing the disappearance of local history, these early preservationists donated artifacts like William Wells’ desk box and Barnabas Horton’s carved chest to the society, ensuring their long-term survival.

Many of these early members of LIHS went on to become supporters of the American Preservation Movement, dedicated to preserving the country’s historic sites and structures. Today, the efforts of regional and national landmark preservation commissions, historical societies, museums, and private citizens ensure that Long Island’s “distinguishing beauty,” its local history and heritage, does not disappear.

Interior of the Long Island Historical Society, circa 1960

Long Island Historical Society photographs (V1974.031.49)

Brooklyn Historical Society