Are All Men Created Equal?

Slavery in Brooklyn Following the Revolutionary War

As one of America’s most recognizable Founding Fathers, portraits of George Washington in full military dress frequently operate as a symbols of the rise of American independence and liberty. BHS’s portrait miniature also represents the opposite: the denial of liberty to Brooklyn’s enslaved people by Nicholas Couwenhoven and other wealthy, landed families.

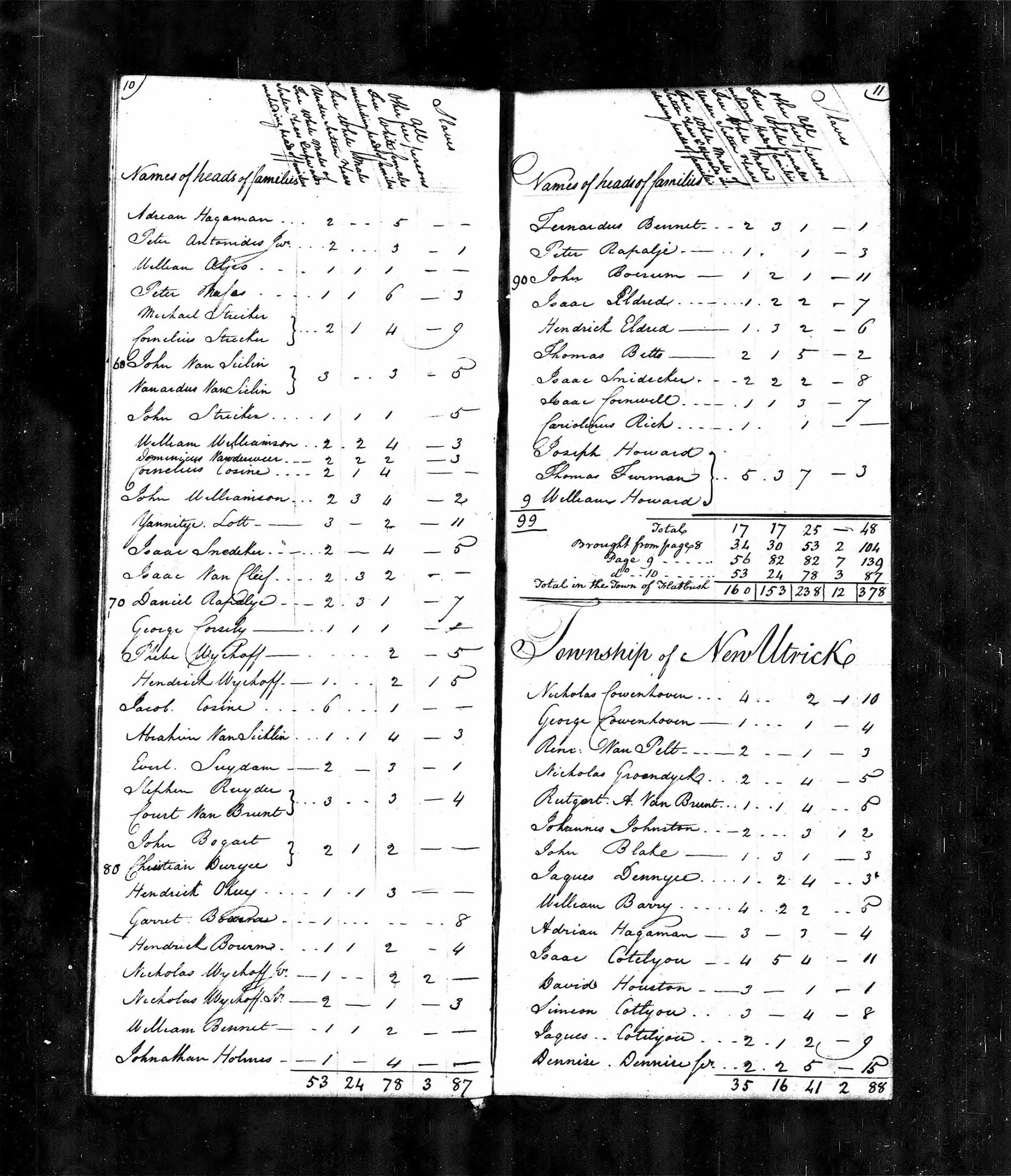

The Revolutionary War did not diminish Brooklynites’ reliance upon slavery. Quite the opposite, in fact. In the 1600s and 1700s, the residents of Brooklyn made their living providing foodstuffs to Manhattan’s markets. As a result, enslaved labor was critical to life throughout Kings County. Following the war, Couwenhoven began growing his estate by purchasing land and enslaved people to work it. The 1790 federal census for the village of New Utrecht shows that Couwenhovens had 10 enslaved people within his household that year, making him one of Brooklyn’s largest slaveholders.

Federal census entry for Nicholas Couwenhoven, 1790

United States Census Bureau

National Archives and Records Administration

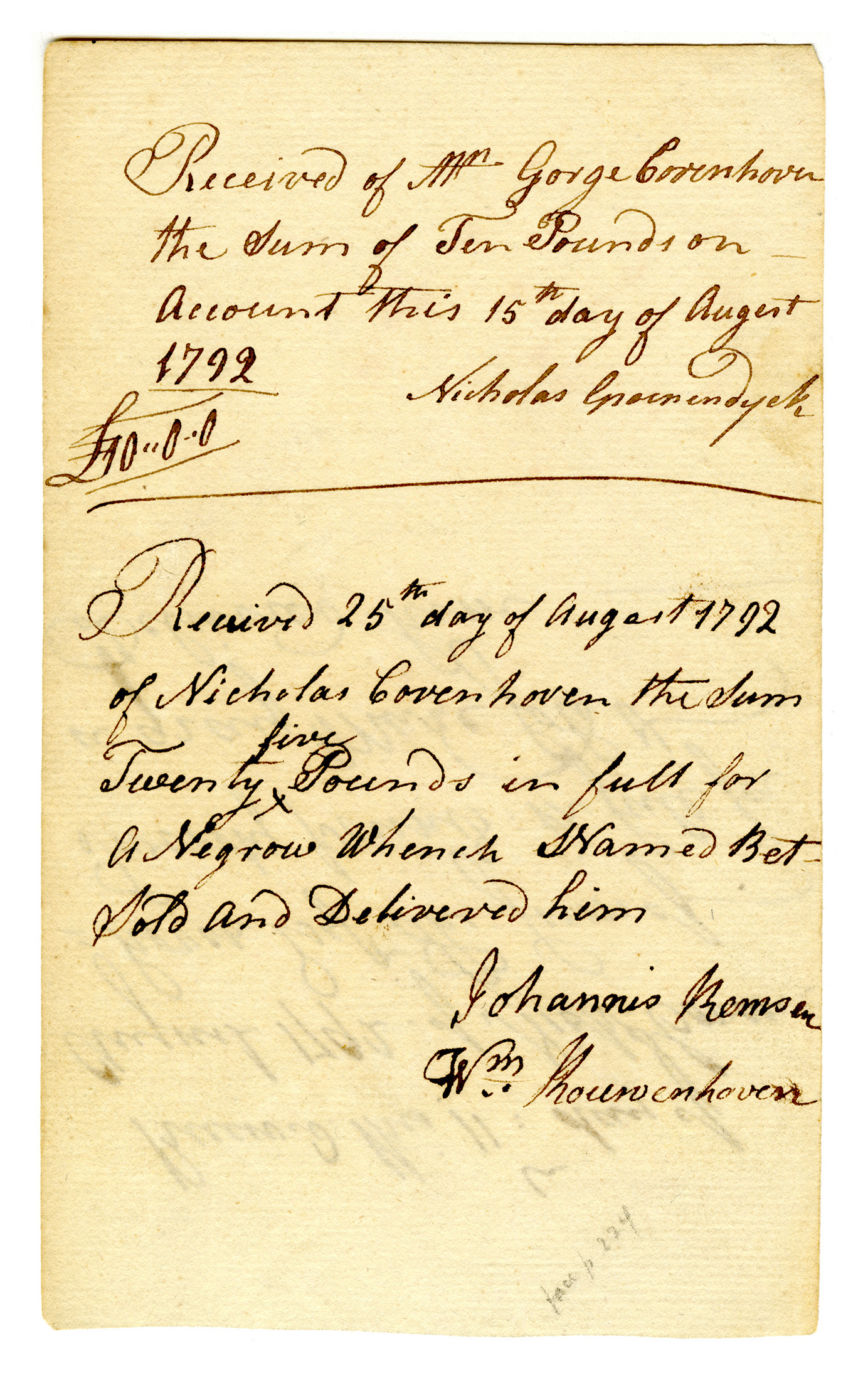

Very little documentation survives today that preserves information about the lives of enslaved Brooklynites. In most cases there are only the bills of sale that transferred human property legally from one owner to another.

Bill of Sale for Bet, 1792

Nicholas Covenhoven papers (ARC.283)

Brooklyn Historical Society

BHS is committed to bringing attention to the history of racial power structures and inequality that defined life in colonial Brooklyn. Those stories are not rare if you know where and how to look for them.

For example, while Couwenhoven’s home, called Bensonhurst, was celebrated in the early 1900s as one of the oldest surviving houses in New Utrecht, a place where Washington himself might have once dined, its basement hid a darker truth, one unseen by visitors. Newspaper accounts of the time recorded rumors of a “sort of pen or cell where the refractory slave was put by way of punishment.” This in the same house where BHS’s portrait miniature was proudly displayed.

Bensonhurst house, New Utrecht, circa 1850–1900

V1972.1.1304

Brooklyn Historical Society